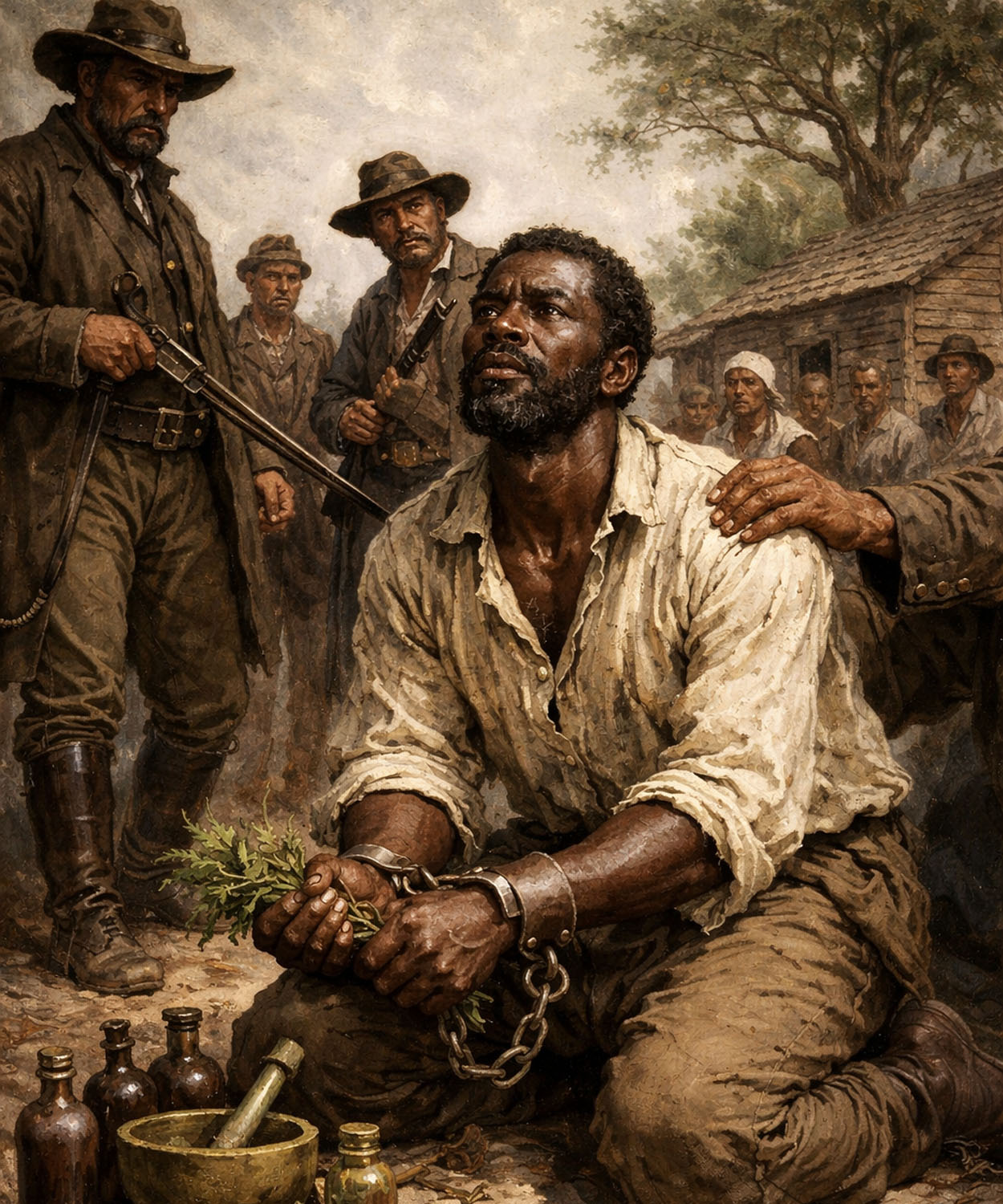

On the night of June 27th, 1848, behind the stables at Riverside Plantation in Bowford County, South Carolina, Master Cornelius Whitfield and three of his most trusted overseers attempted to hang an enslaved healer named Gideon Parker.

The rope was so tight around Gideon’s neck that his skin tore.

Three white men pulled the ends with all their strength, while a fourth held his bound hands behind his back.

It was the third time in 6 months they had tried to kill him.

But Gideon did not die that night, nor the time before, nor the time that would come after.

Because Gideon Parker carried ancestral Yoruba knowledge that made his death nearly impossible.

Knowledge of herbs that healed fatal wounds in days, of roots that made the body resistant to poisons, of rituals that confused the minds of enemies.

For 15 years, he had secretly healed hundreds of enslaved people from diseases the masters considered terminal.

For 15 years, the plantation owners of the South Carolina low country had tried to destroy him.

And for 15 years, Gideon survived hangings, poisonings, beatings, drownings, and even a gunshot to the head.

But survival had a price.

And in the spring of 1848, after watching the masters kill his 16-year-old daughter in an attempt to break him, Gideon Parker decided it was time to show the white men that his knowledge served not only to heal.

It also served to kill.

Gideon Parker was 42 years old in the summer of 1848.

He stood 5 ft and 11 in tall, unusually tall for an enslaved man of that era, with broad shoulders carved from decades of fieldwork and a presence that made even the crulest overseers uncomfortable.

His skin was the deep black of West African lineage, marked with ritual scars on his cheeks that identified him as Yoruba nobility.

Scars that Master Whitfield had tried unsuccessfully to burn away when Gideon first arrived at Riverside Plantation.

His eyes were what people remembered most, dark brown, almost black, with a depth that seemed to see through flesh into soul.

When Gideon looked at you, enslaved people said he saw your sickness before you felt it.

When he looked at white men, they said he saw their death.

Gideon had been born in what the whites called the Gold Coast in a village near Kumasi in the year 186.

His father was a Babalawu, a high priest of Epha, keeper of medicinal knowledge spanning generations.

His mother was a healer specializing in women’s ailments and childbirth.

From age five, Gideon learned the properties of every plant in the tropical forest.

By age 10, he could diagnose illness by examining tongue, eyes, and urine.

By age 15, he had memorized over 300 herbal remedies and could perform surgeries that European doctors of the era could not imagine.

His destiny was to become his village’s chief healer.

Instead, at age 17, Portuguese slavers attacked during a wedding ceremony.

They killed his father with a musket shot to the chest.

They raped his mother in front of the entire village, then slit her throat.

They chained Gideon and 43 others and marched them to the coast.

Of those 44 people, only 19 survived the middle passage.

Gideon was one of them.

He arrived in Charleston, South Carolina in October of 1823.

The auction block on Charalma Street, a tobacco merchant named Elias Peton bought him for $600.

Impressed by the young man’s height and visible strength.

Peton owned a medium-sized plantation near Bowfort with 87 enslaved people and 500 acres of rice fields.

For the first 3 years, Gideon worked the rice patties, standing kneedeep in water 14 hours a day, his back bent, his hands bleeding from the sharp stalks.

He spoke no English.

He tried to die three times, once by refusing food for 11 days.

Once by attempting to drown himself in the Comhe River, once by drinking water hemlock.

Each time something stopped him.

The memory of his father’s voice.

The Yoruba teaching that suicide dishonors the ancestors.

The growing realization that staying alive, learning the language, understanding the enemy might be the only revenge available to him.

In his fourth year of enslavement, an outbreak of cholera swept through the plantation.

23 enslaved people died in 2 weeks.

The white doctor from Bowurt could do nothing.

He prescribed calaml and bloodletting which killed faster than the disease.

Master Peton’s 8-year-old daughter contracted the illness.

The doctor said she would be dead by morning.

That night, Gideon approached the big house.

He had never spoken to Master Peton directly.

He had learned enough English to understand orders, but had never volunteered a word.

Now he stood at the back door and said in broken English, “I can save girl.

I heal her.

My father healer.

His father healer.

10 generation healer.

The overseer beat him for his impudence and dragged him back to the quarters.

But Master Peton’s wife, Catherine, had heard.

She was desperate.

She overruled her husband.

At midnight, they brought Gideon to the girl’s bedroom.

The child was gray, dehydrated, barely breathing.

Gideon examined her quickly.

He asked for specific items.

ginger root which grew wild near the creek.

Charcoal from the blacksmith’s forge.

Honey from the plantation’s beehives.

Clean river water boiled three times.

Salt.

They brought everything within an hour.

Gideon prepared a mixture using measurements and methods his father had taught him.

He gave the girl small sips every 10 minutes.

He placed heated riverstones wrapped in cloth on her abdomen.

He sang a Yoruba healing chant softly, too soft for the white family to hear clearly.

By dawn, the girl’s color had returned.

By sunset, she was sitting up.

By the third day, she was eating solid food.

Master Peton’s wife wept with gratitude.

Master Peton himself, a hard man who had beaten enslaved people to death for minor infractions, looked at Gideon with something approaching respect.

From that day forward, Gideon’s life changed.

They moved him from the fields to a small cabin near the big house.

They gave him extra food rations.

They stopped beating him.

They called on him whenever anyone in the plantation, white or black, fell ill.

Gideon saved Master Peton’s wife from childbed fever.

He cured the overseer’s infected leg that the white doctor wanted to amputate.

He treated snake bites, infections, broken bones, consumption, yellow fever, typhoid, dissentry.

His success rate was extraordinary.

While the white doctor’s treatments killed half his patients, Gideon’s patients almost always survived.

Word spread to neighboring plantations.

masters began requesting Gideon’s services for their enslaved workers, not out of compassion, but because dead slaves represented lost capital, and Gideon could keep valuable property alive.

Master Peton started renting Gideon out for $5 per treatment, a lucrative side business.

But Gideon had not forgotten who he was.

Every cure he performed for enslaved people, he did with his whole heart.

Every cure he performed for white people, he did with calculated precision, just enough to keep them alive, to maintain his value, to protect himself.

And secretly, using the mobility his position granted him, Gideon began building something the masters could not see, a network.

Every plantation he visited, every enslaved person he treated, became part of a web of communication.

He taught them herbal remedies they could make themselves.

He taught them which roots could induce miscarriage when a woman could not bear to bring another child into slavery.

He taught them which plants could make a master sick enough to be bedridden for weeks.

He taught them codes hidden in spirituals and folktales.

He never advocated for open rebellion.

That was suicide.

But he gave enslaved people tools for survival, for resistance, for sabotage, for hope.

Over 15 years, Gideon treated and taught hundreds of enslaved people across eight plantations in Bowford County.

He became a legend.

Some called him the African.

Some called him the doctor.

Some called him the Oia man.

The enslaved people trusted him absolutely.

And that was exactly what made the white masters fear him.

Master Elias Peton died in 1842 of a heart attack while beating a field hand.

Gideon had been away treating patients at another plantation and had not been present to intervene.

Peton’s widow sold the plantation to Cornelius Whitfield, a brutal man from Charleston who had made his fortune in the domestic slave trade.

Whitfield was 45 years old, short and stocky, with thinning red hair, pale skin marked by broken blood vessels from excessive drinking, and small blue eyes that radiated cruelty.

He had purchased and sold over 2,000 enslaved people in his career, separating families without a second thought, selling children as young as six, breeding women like livestock.

He saw enslaved people as nothing more than inventory.

When he took over Riverside Plantation in January of 1843, he implemented new rules designed to maximize profit through terror.

Whitfield increased work hours to 16 per day during planting and harvest season.

He reduced food rations by 1/3.

He abolished the practice of giving enslaved people Sunday afternoons off.

He brought in a new overseer named Samuel Hackit, a sadist from Mississippi who had killed at least three enslaved people during his previous employment.

Hackett was 38 years old, tall and muscular with a scarred face and hands- like hammers.

He carried a bullhip made from braided rawhide that could strip flesh from bone with a single strike.

He used it liberally.

Hackett believed that enslaved people should be in constant fear.

that fear increased productivity, that mercy was weakness.

Within 6 months of Whitfield’s takeover, 12 enslaved people had died from overwork, malnutrition, or beatings.

Another eight had been sold.

The atmosphere at Riverside transformed from harsh but survivable to a living nightmare.

Gideon immediately recognized the danger.

Under Peton, he had enjoyed a degree of protection due to his value as a healer.

Under Whitfield and Hackit, that protection evaporated.

Whitfield saw Gideon as a threat to the new order, an enslaved person who moved freely between plantations, who spoke with authority, who commanded respect from other enslaved people, who possessed knowledge that white people did not understand and could not control.

In March of 1843, during a meeting of plantation owners at the Bowford Courthouse, Whitfield openly stated his opinion.

That African healer is dangerous.

He knows too much.

The slaves worship him.

If there’s ever an uprising, he’ll be at the center of it.

We should get rid of him.

Several other owners agreed.

Others argued that Gideon was too valuable to kill.

The debate continued through multiple meetings.

Meanwhile, Hackett, the overseer, began a campaign of harassment.

He restricted Gideon’s movements.

He confiscated the herbs Gideon kept in his cabin.

He beat enslaved people who sought Gideon’s help.

He spread rumors that Gideon practiced devil worship and black magic.

He told the field hands that anyone caught near Gideon’s cabin at night would receive 50 lashes.

Gideon understood what was happening.

They were isolating him, preparing to destroy him.

He prepared for the inevitable.

He hid herbs in secret locations across the plantation, buried in sealed clay pots near the creek, concealed in hollow tree trunks in the forest, tucked into the rafters of the old barn.

He taught three trusted enslaved women his most important remedies, making them memorize recipes through repetition.

He began treating the illnesses of field hands at night in the forest away from watching eyes.

He stopped treating white people entirely, claiming his power had mysteriously faded.

This infuriated Whitfield.

In August of 1843, when Witfield’s brother visited from Charleston with a severe fever, Witfield ordered Gideon to treat him.

Gideon refused.

Hackit dragged Gideon to the whipping post and gave him 30 lashes.

Gideon’s back split open like a gutted fish.

They threw him in his cabin and left him to die.

That was their first mistake.

Because Gideon did not die.

Using herbs he had hidden under his floorboards, he created a paste that stopped infection and accelerated healing.

Within a week, the wounds had closed.

Within two weeks, he was walking.

Within 3 weeks, the scars had faded to thin white lines.

The enslaved people whispered in awe.

The white people muttered about witchcraft.

Witfield became even more determined to end Gideon’s life.

Gideon had one vulnerability that the masters eventually discovered.

His daughter, Grace.

Grace was 16 years old in 1848, born in 1832 to Gideon and a woman named Abigail, who had died in childbirth, delivering a stillborn son in 1835.

Grace was the light of Gideon’s existence, the only person who could make him smile, the only reason he had not attempted escape or suicide during his darkest years.

She had her mother’s beauty, smooth skin, bright eyes, graceful movements, and her father’s intelligence.

Gideon had taught her everything he knew about healing.

She could identify [clears throat] over a 100 medicinal plants.

She could set broken bones.

She could treat fevers, wounds, and infections.

She was learning fast, absorbing knowledge like soil absorbs rain.

Gideon dreamed that one day, impossibly, she might be free, that she might use her knowledge to help people without chains, that his father’s legacy might continue through her.

It was a foolish dream in the South Carolina of 1848.

But hope was all he had.

Master Whitfield noticed grace, noticed how Gideon looked at her, noticed how she was the only person who could make the African healer vulnerable.

In February of 1848, Whitfield proposed a deal to Gideon.

Continue treating my enslaved workers.

Obey every order.

Cause no trouble, and your daughter stays safe.

Refuse me again and she becomes a fieldand or worse.

Gideon understood worse.

Whitfield was known for sexually assaulting enslaved women.

His previous plantation in Charleston had over 30 mixed race children, all enslaved.

The thought of Witfield touching Grace made Gideon’s vision go red.

But what could he do? If he attacked Whitfield, they would both die.

If he ran with Grace, they would be caught within days and tortured to death.

If he complied, Grace remained in danger but alive.

He chose temporary compliance, buying time, searching for options that did not exist.

For 3 months, Gideon returned to treating white patients.

He swallowed his pride.

He bowed his head.

He said, “Yes, master and no master like a good slave, and he began to plan.

” The first attempt to kill Gideon happened on April 14th, 1848, a Sunday evening, just after sunset.

Gideon was walking back to his cabin from the creek where he had been gathering wild ginger.

Three white men stepped out from behind the blacksmith’s shed.

Overseer Hackit and two slave patrollers named Dutch Karnney and Tom Blackwood.

All three were drunk on whiskey.

Hackett said, “Master Witfield’s tired of you African.

Says you’re a dangerous influence.

Says the world’s better off without you.

” They did not give Gideon a chance to respond.

Karnney and Blackwood grabbed his arms while Hackett pulled out a knife and drove it into Gideon’s abdomen just below the rib cage, twisting the blade.

They felt the blade sink deep into flesh.

They saw blood pour from the wound, soaking Gideon’s shirt, dripping onto the dirt.

They held him upright for 10 seconds, watching his eyes go glassy, then let him drop.

Hacked kicked him in the head.

“Bleed out, witch doctor,” he said.

Then they left him there lying in a pool of his own blood behind the shed and went to report to Master Whitfield that the job was done.

But the job was not done.

What the three white men did not know was that Gideon had been expecting an attack.

For 2 weeks he had carried with him at all times a specially prepared herbal packet sewn into the lining of his shirt pressed against his abdomen.

The packet contained a paste made from yarrow plantain, golden seal root, cayenne pepper, and spider silk, all bound with beeswax.

When Hackit’s knife pierced his shirt, it first struck the packet.

The blade penetrated, but the paste immediately entered the wound, acting as both coagulant and antiseptic.

The yrow stopped bleeding.

The plantain prevented infection.

The golden seal accelerated healing.

The cayenne pepper increased blood flow to the wound site.

The spider silk acted as a natural suture.

Gideon also carried with him a bladder filled with pig’s blood concealed in his waistband.

When the knife struck, he squeezed the bladder, releasing blood that mixed with his own, making the wound appear far worse than it was.

The technique was one his father had taught him for surviving knife attacks during tribal warfare.

It required perfect timing and nerve.

Gideon had both.

After the three men left, Gideon lay still for 5 minutes, ensuring they were gone.

Then he rose, stumbled to the creek, washed the wound thoroughly with cold water, applied more healing paste from his hidden supply, and bound his abdomen tightly with strips of cloth.

The actual knife wound was 2 in deep, painful, but not fatal, missing all vital organs by design because Gideon had controlled his body position during the attack.

Over the next two days, he remained in his cabin, allowing enslaved people to spread the word that he was dying.

On the third day, he walked out of his cabin fully upright, the wound nearly healed.

When overseer Hackett saw him, the overseer’s face went white as cotton.

“How?” Hackit whispered, “How are you alive?” Gideon looked at him with those deep black eyes and said nothing.

The enslaved people began to say that Gideon Parker could not be killed.

The white people began to believe it, too, and they became afraid.

The second attempt happened on May 21st, 1848.

Master Whitfield decided to use poison.

He invited Gideon to the big house under the pretense of treating a sick horse, then offered him a cup of water.

The water contained a massive dose of arsenic, enough to kill three men.

Whitfield watched Gideon drink the entire cup.

Within minutes, Gideon should have been writhing on the floor, vomiting blood, dying in agony.

Instead, he stood calmly, thanked Master Witfield for the water, and walked back to his cabin.

Witfield was baffled and terrified.

What he did not know was that for the past month, Gideon had been consuming small doses of various poisons daily, building immunity through a process called mythritism.

He ingested tiny amounts of arsenic, strick nine, belladona, hemlock, and oleander, gradually increasing the dosage.

His body learned to metabolize the toxins.

Additionally, before drinking anything offered by white people, Gideon coated his mouth and throat with a mixture of activated charcoal and bentonite clay, which absorbed poisons before they could enter his bloodstream.

When he drank Whitfield’s poisoned water, the arsenic bound to the clay and charcoal passed through his digestive system harmlessly and was expelled within hours.

Gideon suffered mild nsia that night, but nothing more.

By morning, he was fine.

The legend grew stronger.

Gideon Parker is protected by African gods.

He cannot be poisoned.

After two failed attempts, Master Witfield convened a meeting with four neighboring plantation owners.

Thaddius Grimshaw, owner of Oakwood Plantation.

Montgomery Sheffield, owner of Fairfield Plantation.

Jeremiah Blackwood, owner of Magnolia Grove, and Silas Peton, nephew of Gideon’s former master.

These five men represented over 600 enslaved people and 3,000 acres of land.

They met in secret on June 10th, 1848 at the Bowurt Gentleman’s Club, a private establishment where the Low Country elite discussed business over brandy and cigars.

The topic, what to do about Gideon Parker.

Whitfield spoke first.

Gentlemen, we have a problem that threatens the stability of our entire system.

This African healer has survived stabbing and poisoning.

The slaves believe he’s immortal.

If we don’t kill him convincingly and publicly, we risk giving enslaved people hope that resistance is possible.

Hope is more dangerous than any weapon.

Grimshaw agreed.

I’ve heard the stories.

My own slaves whisper about him.

They say the African has power beyond white understanding.

It’s making them less compliant.

Sheffield suggested, “Hang him publicly.

Make it brutal.

Leave the body on display for a week as a warning.

” Blackwood added, “We need to destroy his reputation first.

Accuse him of raping a white woman.

No trial, just immediate execution.

Legal under South Carolina law.

Peton, who had some residual respect for Gideon, hesitated.

The man is genuinely useful.

He’s saved lives.

Is there no way to control him without killing him? Whitfield slammed his fist on the table.

Control.

We cannot control something we don’t understand.

Fear is control.

And right now, we’re the ones afraid.

That ends tonight.

They formulated a plan.

Step one, seize Gideon’s daughter, Grace, and use her as bait.

Step two, lure Gideon to an isolated location under pretense of treating a dying child.

Step three, four men would ambush him, beat him unconscious, hang him from an oak tree, and ensure he was dead before leaving.

Step four, leave the body hanging for 3 days as a message to all enslaved people in Bowford County.

The five plantation owners shook hands and drank a toast.

To civilization, to order, to white supremacy.

They were confident.

They outnumbered Gideon.

They had surprise.

They had weapons.

They had the law.

What they did not have was understanding of who they were dealing with.

On June 27th, 1848, at approximately 8:00 in the evening, Overseer Hackett approached Gideon’s cabin with urgent news.

There’s a child dying at the Grimshaw plantation.

10 years old, fever and convulsions.

Master Grimshaw sent for you specifically.

Says you’re the only one who can save her.

But you must come now.

Gideon knew instantly it was a trap.

No white master sent for a black healer at night, unless desperation outweighed racism.

Grimshaw had never requested Gideon’s services before.

The timing was suspicious, but Gideon also knew that refusing would be seen as insubordination, punishable by death, and would endanger Grace.

So he made a choice.

Walk into the trap knowingly, prepared, and turn the hunters into the hunted.

He gathered his medicine bag, but inside, instead of healing herbs, he placed items of a different nature.

A small knife made from sharpened iron, stolen from the blacksmith months ago, and hidden.

Packets of cayenne pepper powder that could blind an attacker.

a vial of concentrated oleander extract, deadly if applied to open wounds, and strips of cloth soaked in gyson tincture, which induced hallucinations and paralysis when absorbed through skin.

He also ate a small piece of psilocybin mushroom, enough to sharpen his senses, slow his perception of time, and increase his reaction speed, a technique his father had taught him for ceremonial combat.

Then he followed Hackit into the darkness.

They walked through the forest toward Grimshaw’s plantation about 2 mi north of Riverside.

The moon was nearly full, casting silver light through the pine trees.

Cricket sang.

An owl called in the distance.

Gideon’s senses were extraordinarily heightened from the mushroom.

He could hear Hackit’s breathing, smell the man’s sweat and whiskey, sense the tension in the overseer’s gate.

about halfway to their destination.

Hackit led him off the main path toward a clearing near the old tobacco barn that had been abandoned for years.

As they entered the clearing, three men stepped out from behind trees.

Master Whitfield, slave patroller Dutch Kernney and Montgomery Sheffield.

All four white men held weapons.

Whitfield a pistol.

The others thick oak clubs and rope.

Whitfield smiled coldly.

Hello, African.

We’ve been waiting for you.

Gideon did not respond.

He assessed the situation with pre-tnatural calm.

Four men armed spread in a semicircle.

Trees behind him limiting retreat.

They expected him to run or beg.

He would do neither.

Whitfield continued, “You’ve been a problem for too long.

Tonight you die properly this time.

We’re going to beat you until you can’t move, then hang you from that oak tree over there and watch you strangle slowly.

And just so you know, your daughter Grace is locked in my cellar right now.

After you’re dead, I’m going to visit her personally every night until she breaks or dies.

That’s your legacy, witch doctor.

Your death and her suffering.

Something inside Gideon snapped.

Not the hot rage of impulse, but the cold, calculated fury of a man who has nothing left to lose.

For 15 years he had healed.

He had helped.

He had used his knowledge to preserve life.

Tonight that changed.

Tonight his father’s teachings about healing would transform into teachings about killing.

Because the same knowledge that saves can also destroy.

The same herbs that cure can poison.

The same hands that set bones can break them.

Gideon reached into his medicine bag calmly, as if retrieving herbs.

The four white men watched, curious, not yet alarmed.

Then Gideon threw the cayenne pepper powder directly into Whitfields and Kern’s faces with perfect accuracy.

Both men screamed, clawing at their eyes, temporarily blinded.

In the same motion, Gideon pulled out the sharpened iron knife and lunged at Hackit, the closest and most dangerous opponent.

Hackit swung his club, but Gideon’s mushroom enhanced reflexes made the attack seem slow.

He sidestepped, grabbed Hackit’s wrist, and drove the knife upward into the soft tissue under Hackett’s jaw, through the roof of the mouth, into the brain.

Hackett’s eyes widened in shock.

He made a wet gurgling sound.

Gideon pulled the knife free and let the overseer’s body drop.

Montgomery Sheffield charged with his club raised.

Gideon threw the gyms weed soaked cloth strips at Sheffield’s face.

The cloth wrapped around the man’s nose and mouth.

Sheffield inhaled deeply in surprise, absorbing the tincture.

Within seconds, his pupils dilated massively.

His coordination failed.

He swung the club wildly, hitting nothing.

He began to scream, “Snakes! There are snakes everywhere.

Get them off me!” He fell to his knees, clawing at invisible reptiles, completely incapacitated by hallucinations.

That left Witfield and Karnney, both still blinded by Cayenne pepper, stumbling and cursing.

Whitfield fired his pistol blindly three times.

All three shots missed.

Gideon approached Whitfield with calm deliberation.

He took the pistol from the master’s hand.

Witfield was too disoriented to resist effectively.

Then Gideon spoke, his voice quiet but filled with ancient authority.

You should have left me alone, Master Whitfield.

You should have left my daughter alone.

But you didn’t.

So now you learn what my people knew for a thousand years.

Healers make the best killers because we know exactly where to cut to cause maximum pain without quick death.

Gideon used the knife to make shallow cuts on Whitfield’s arms, legs, and torso.

Dozens of small incisions, each one bleeding freely, but avoiding arteries.

Then he applied the concentrated oleander extract to the wounds.

Oleander is one of the most poisonous plants in the world.

When its toxin enters the bloodstream, it attacks the heart, causing irregular rhythm, nausea, vomiting, seizures, and eventually cardiac arrest.

But death is not quick.

It takes hours, painful hours.

Gideon ensured Whitfield absorbed enough to guarantee death, but not so much as to cause immediate collapse.

He wanted the master to suffer.

Whitfield began to feel the effects within minutes.

Severe stomach cramps, vision blurring further, heart pounding irregularly, weakness spreading through his limbs.

Gideon turned to Karnney, who was still rubbing his burning eyes.

He knocked the patroller unconscious with a single punch to the temple, then tied him to a tree using the rope they had brought to hang Gideon.

He cut Karnney’s shirt open and carved a message into the man’s chest with the knife.

Not deep enough to kill, just deep enough to scar permanently.

This is what happens to men who hunt healers.

He applied yarrow paste to the wounds to prevent death from infection.

Gideon wanted Kernney to live, to carry the message, to testify to what the African could do.

Sheffield was still hallucinating violently, screaming about demons and fire.

Gideon approached him and injected a small amount of detura extract into his neck using a hollow reed.

Enough to keep him in a hallucinogenic state for days, but not enough to kill.

Sheffield would be found eventually babbling incoherently, his mind temporarily shattered.

Whitfield was on his hands and knees now, vomiting blood, his heart failing progressively.

Gideon crouched beside him and spoke softly.

You will die tonight, Master Witfield, slowly, painfully.

Your heart will stop within 2 hours.

Before you go, know this.

Your death means nothing to me.

You are not revenge.

You are a warning.

I am going to free my daughter.

I am going to walk out of South Carolina.

And if any man tries to stop me, he will die like you.

Tell that to your devil when you meet him.

” Whitfield tried to respond, but could only cough blood.

Gideon stood, gathered his supplies, and walked away.

Behind him, Whitfield collapsed face first into the dirt, convulsing.

By midnight, Master Cornelius Whitfield was dead, his poisoned heart finally stopping.

His body was found at dawn by enslaved field hands who had been sent to look for him.

The sight of a white master lying dead, covered in his own vomit and blood, sent shock waves through Bowford County.

Gideon moved quickly.

He had perhaps 12 hours before a massive manhunt began.

He ran back to Riverside Plantation, avoiding roads, moving through forest and swamp like a ghost.

He reached Whitfield’s big house around 10:00 at night.

The house was mostly dark, only a single lantern burning in the kitchen.

Whitfield’s wife, Constance, was there along with the house cook, an enslaved woman named Ruth.

Gideon entered through the back door silently.

Ruth gasped when she saw him, but said nothing.

Constance Whitfield screamed.

Gideon said calmly.

Your husband is dead.

I killed him.

Now I’m taking my daughter.

Where is she? Constance backed against the wall, trembling.

The cellar, she whispered.

The key is in Cornelius’s study.

Gideon retrieved the key, went to the cellar, and found Grace locked in a small windowless room, chained to the wall by her ankle.

She was unharmed physically, but terrified.

When she saw her father, she burst into tears.

Gideon broke the chain with a hammer from the cellar workshop, gathered Grace in his arms, and carried her up the stairs.

Before leaving, he turned to Constance Whitfield and said, “Tell them Gideon Parker is gone.

Tell them he cannot be killed.

Tell them he will return if they hunt him.

Tell them the age of helpless slaves is ending.

” Then he and Grace disappeared into the night.

They moved north, guided by the North Star, using every trick Gideon had learned over 25 years of survival.

They traveled only at night, sleeping hidden during the day.

They waded through creeks to hide their scent from blood hounds.

They ate wild plants Gideon identified by moonlight.

They avoided roads and towns.

On the third night, they reached a safe house on the Underground Railroad operated by a free black family in Georgetown.

The family gave them food, clean clothes, and directions to the next station.

From Georgetown, they moved to Wilmington, North Carolina.

From Wilmington to Norfolk, Virginia.

From Norfolk to Washington, D.

C.

The journey took 6 weeks.

Every day, Gideon expected to be captured.

Every night, he prepared poisons and weapons in case they were cornered.

But they were lucky.

Or perhaps the legend of the unkillable African healer preceded them and slave catchers decided he was too dangerous to pursue.

On August 9th, 1848, Gideon and Grace crossed into Pennsylvania, a free state.

For the first time in 25 years, Gideon was no longer enslaved.

He collapsed on the Pennsylvania side of the border and wept.

They settled in Philadelphia in a community of free black people and former slaves.

Gideon opened a medical practice using his knowledge to treat the poor and the sick without discrimination.

His reputation spread quickly.

Abolitionists sought him out, asking him to speak at rallies, to tell his story, to inspire others.

Gideon refused public speaking.

He feared attention would bring slave catchers.

but he wrote an anonymous account of his life that was published in an abolitionist newspaper under the title testimony of an African healer.

The account detailed the tortures of slavery, the intelligence of enslaved people, the brutality of masters, and the possibility of resistance.

It was reprinted in dozens of newspapers across the north.

Grace studied medicine formally, learning from both her father’s African knowledge and European medical science.

She became one of the first African-American women to practice medicine in Philadelphia.

She treated thousands of patients over her long career and never forgot the night her father killed to save her.

Back in South Carolina, the death of Master Cornelius Whitfield caused panic among plantation owners.

An enslaved man had killed a white master and escaped.

It was their worst nightmare.

The story spread rapidly, growing with each retelling.

Some said Gideon had killed 10 men.

Some said he used supernatural powers.

Some said he was organizing a slave rebellion from the north.

None of it was true.

But the fear was real.

Plantation owners across the Low Country increased security, hired more overseers, purchased more weapons, and treated enslaved people with even greater brutality, hoping to prevent further uprisings.

But the brutality backfired.

Enslaved people heard the story of Gideon Parker and drew hope from it.

If one man could kill his oppressor and escape, perhaps others could, too.

Small acts of resistance increased.

Tools broken deliberately, fires started accidentally, overseers ambushed in the dark.

Between 1848 and 1861, at least 12 overseers and three plantation owners in Bowford County died under suspicious circumstances, poisonings that doctors could not explain, accidents that seemed too convenient, disappearances that were never solved.

Whether Gideon’s actions directly inspired these deaths is impossible to prove, but the correlation is clear.

The legend of the African healer who could not be killed, became a symbol of possibility in an age of despair.

Dutch Kernney, the slave patroller who survived Gideon’s attack, never fully recovered.

The scars on his chest remained visible for the rest of his life, and he told anyone who would listen about the night the African healer turned into a demon.

He became obsessed with the idea that Gideon possessed supernatural powers and spent years researching hudoo, conjure, and African spirituality, trying to understand what he had experienced.

Eventually, he published a pamphlet titled The African Witch Doctor, a warning to Christian America, in which he claimed that allowing enslaved people to maintain their African traditions was dangerous because it gave them access to dark powers.

The pamphlet was widely mocked by educated people, but taken seriously by some religious communities.

It contributed to laws prohibiting enslaved people from practicing African religions and gathering for non-Christian ceremonies.

Ironically, Kern’s testimony proved what abolitionists had been arguing.

Enslaved people were not passive childlike beings needing white guardianship.

They were intelligent, resourceful, and capable of sophisticated resistance.

They were human beings fighting for freedom with whatever tools they had.

And sometimes those tools were deadly.

Montgomery Sheffield, who had been dosed with gyms weed and spent 3 days hallucinating, was found wandering naked in the forest, babbling about snakes and demons.

He was taken to his plantation where a doctor diagnosed him with brain fever and recommended rest.

Sheffield’s hallucinations eventually subsided, but his mental state never fully recovered.

He became paranoid, obsessed with checking his food for poison, afraid of his own enslaved workers, jumping at shadows.

Within a year, he sold his plantation and moved to Charleston, where he lived in isolation, until his death in 1853.

His family attributed his breakdown to excessive exposure to savage influences, meaning Gideon.

Modern doctors would probably diagnose post-traumatic stress disorder.

Whatever the cause, Sheffield’s destruction was complete without Gideon ever touching him again.

The mind, Gideon knew, was often more fragile than the body.

Samuel Hackett, the brutal overseer, was buried in an unmarked grave at Riverside Plantation.

No funeral service was held.

His death was recorded in official documents as killed by a runaway slave, which was technically accurate, but omitted the context that made his death an act of justified self-defense.

Hackett’s widow received no compensation from Witfield’s estate because Witfield had died before settling Hackett’s final wages.

She and her children fell into poverty.

Enslaved people at Riverside Plantation, when they learned of Hackett’s death, held a secret celebration in the quarters, singing spirituals about deliverance from evil, when woman, who had been beaten nearly to death by Hackett two years earlier, danced until dawn.

Justice, when it came in the world of slavery, was rare and precious.

The bodies of Cornelius Whitfield and Samuel Hackett were eventually examined by a physician from Charleston named Dr.

Edmund Hargrove, who specialized in forensic medicine.

Hargro’s report, preserved in South Carolina court records, noted, “Master Witfield appears to have died from cardiac failure induced by a toxin of unknown origin.

The symptoms suggest digitalis or a similar cardiac glycoside, though no common source is evident.

The precision of the wounds on his body indicates medical knowledge.

” Overseer Hackett’s death resulted from a penetrating wound to the brain via the sublingual route, a method I have seen only in military combat manuals describing assassinations.

Whoever killed these men possessed both advanced anatomical knowledge and coldblooded efficiency.

This was not the work of a common slave.

This was execution.

Harrove’s report was suppressed by South Carolina authorities because it contradicted the narrative that enslaved people were intellectually inferior and incapable of sophisticated violence.

Acknowledging that an enslaved African possessed medical knowledge superior to most white doctors would undermine the entire ideology of slavery.

So the report was filed away and forgotten.

But it remains in the archives a testament to Gideon’s skill.

In the years following his escape, Gideon continued his medical practice in Philadelphia.

He treated rich and poor, black and white, without discrimination.

He charged wealthy patients substantial fees and used the money to treat poor patients for free.

He became moderately prosperous, owning a small house in the black community and employing two assistants.

He never married again.

His heart remained with his deceased wife, Abigail, but he found companionship in the community of free black people and abolitionists.

He corresponded with Frederick Douglas, who had escaped slavery from Maryland in 1838.

He met Harriet Tubman, the legendary underground railroad conductor in 1851 and provided her with medical supplies for her rescue missions.

He donated money to abolitionist newspapers and underground railroad operations.

He trained young black people in medical techniques, passing on his father’s knowledge to a new generation.

He lived quietly, avoiding attention.

But his impact was profound.

By the time of his death in 1871 at age 65, Gideon had trained 17 black medical practitioners, treated thousands of patients, and saved countless lives.

He died peacefully in his sleep, surrounded by his daughter, Grace, and her three children, the first generation of his family born free.

Grace Parker became Grace Parker Williams after marrying a black school teacher named Thomas Williams in 1855.

She opened a clinic for women and children in Philadelphia and gained recognition for her work treating gynecological conditions and delivering babies safely at a time when childbirth mortality was extremely high.

She wrote several medical papers on herbal remedies, combining her father’s African knowledge with European science, though she published under her husband’s name because medical journals would not accept work from women, especially black women.

She lived until 194, age 72, and saw the end of slavery, the reconstruction era, and the beginning of the Jim Crow era.

In her private journals, preserved by her descendants and now held at the Smithsonian Institution, she wrote extensively about her father.

One entry dated June 27th, 1871, the anniversary of Whitfield’s death, reads, “Today I remember the night my father became something he never wanted to be, a killer.

He was a healer.

Every instinct in his body and soul was oriented toward preserving life.

But when Master Whitfield threatened me, when he gave my father the choice between complicity and action, my father chose action.

He did not choose violence because he loved violence.

He chose violence because it was the only language the oppressors understood.

He did not want to kill.

He wanted to heal.

But the system of slavery made healing impossible without first destroying those who caused the wounds.

I think about this often about how many gentle people were forced to become hard.

How many natural healers became warriors? How many dreams of peace were drowned in the necessity of survival? My father once told me, “Grace, in Africa, I would have spent my life helping people live longer, better lives.

” In America, I spent my life keeping people alive just long enough to suffer more.

That is what slavery does.

It turns healers into survivors.

And sometimes, when pushed far enough, it turns survivors into avengers.

He was right.

He was always right.

I The story of Gideon Parker spread through the enslaved communities of the South via the Grapevine Telegraph, the invisible network of communication that connected plantations despite white efforts to isolate enslaved people.

Field hands visiting neighboring plantations shared the story.

Enslaved people sold to new masters carried it with them.

Preachers incorporated it into coded spirituals.

Within 5 years, some version of the tale had reached enslaved people in every southern state.

The details varied.

In some versions, Gideon killed 20 men.

In others, he used magic spells to make himself bulletproof.

In still others, he turned into an animal and escaped.

But the core truth remained consistent.

An enslaved healer had killed his oppressor and escaped to freedom.

And that truth, regardless of embellishment, gave hope.

If Gideon Parker could survive, maybe others could, too.

If one man could fight back successfully, maybe resistance was not futile.

The masters had weapons and laws and armies.

But the enslaved had knowledge, courage, and the will to be free.

Sometimes that was enough.

There is a memorial to Gideon Parker in the African-American Museum in Philadelphia.

It is small, a bronze plaque with his name, dates, and a brief description.

Gideon Parker, circa 186 to 1871.

Healer, father, and survivor of American slavery.

Escaped from South Carolina in 1848 after defending himself against attempted murder.

established medical practice in Philadelphia, treating thousands without regard to race or ability to pay.

His life is a testament to the intelligence, skill, and resilience of enslaved African people.

The plaque does not mention that he killed four men.

It does not describe the brutal methods he used.

It does not judge whether his actions were right or wrong.

It simply acknowledges that he existed, that he resisted, and that he survived.

In a country that tried very hard to erase enslaved people from history, to reduce them to property without stories or names or humanity, that simple acknowledgement is itself an act of resistance.

Saying the name, remembering the person, preserving the story.

That is how we honor those who fought when fighting seemed impossible.

What can we learn from Gideon Parker’s story? That systems of oppression rely on the oppressed remaining passive.

That enslaved people were not passive.

They resisted constantly in ways large and small.

That knowledge is power.

Whether it is the knowledge to heal or the knowledge to harm.

That human beings when pushed beyond all limits will fight back often with intelligence and skill that surprises their oppressors.

that fathers will kill to protect their children, that healers can become warriors when necessary, that survival sometimes requires violence, that freedom is worth any price.

These lessons are uncomfortable.

They do not fit neatly into sanitized narratives about slavery where noble abolitionists freed helpless enslaved people through moral persuasion and legislation.

The truth is messier, bloodier, and more human.

Enslaved people freed themselves through escape, through rebellion, through sabotage, through survival, and yes, sometimes through killing those who would not let them live.

Gideon Parker’s story is one of thousands.

Most of those stories are lost.

But the ones that survived like Gideonss must be told not to glorify violence, but to recognize that enslaved people were full human beings with agency, intelligence, and the capacity to fight for their own liberation.

They were not victims waiting to be saved.

They were warriors, strategists, survivors, and avengers, and they deserve to be remembered as such.

If you are feeling a complex mix of emotions right now, anger at the system that forced a healer to become a killer, sadness for the countless lives destroyed by slavery, admiration for Gideon’s intelligence and courage, discomfort with the violence he used, that is appropriate.

History is not simple.

Slavery was an unimaginable evil that corrupted everyone it touched, white and black alike.

It forced good people into impossible choices.

It destroyed families, cultures, and lives on a scale almost incomprehensible.

The violence of slavery, the daily beatings, rapes, murders, and soul destroying oppression, went on for 246 years in what became the United States.

The violence of resistance, like Gideon’s actions, was a reaction to that systematic brutality.

It was not equivalent.

The enslaver and the enslaved were not morally comparable.

One side fought to maintain an evil system.

The other side fought to survive and be free.

We do not have to condone every act of violence committed by enslaved people to recognize that they had every right to resist by any means necessary.

And we must remember that the history we were taught in school, the history of peaceful progress and gradual improvement is a sanitized lie designed to make white people comfortable.

The real history is written in blood, in the blood of enslaved people who died in chains and the blood of oppressors who died trying to maintain those chains.

Both kinds of blood soaked the American soil.

Only by acknowledging both can we understand what slavery truly was and what freedom truly cost.

Today in the 21st century the physical chains of chatt slavery are gone.

But the legacies remain.

Mass incarceration disproportionately targets black men creating a new form of forced labor.

Police brutality continues to kill black people with impunity.

Economic inequality deliberately constructed through centuries of exploitation traps millions in poverty.

Educational disparities, housing discrimination, healthcare inequities, all of these are direct descendants of slavery.

The fight that Gideon Parker fought is not over.

It has changed form, but it continues.

And just as Gideon used his knowledge, his intelligence, and his courage to resist, so too must we use whatever tools we have to continue the struggle for true equality and justice.

Remember Gideon Parker.

Remember Grace Parker Williams.

Remember the millions of enslaved people whose names we do not know, but whose resistance made freedom possible.

Remember that healing sometimes requires cutting away disease.

Remember that knowledge is power.

Remember that the powerful fear nothing more than the moment when the oppressed stop accepting oppression.

Remember that systems change not through patience and polite requests but through sustained resistance and the refusal to bow.

Remember and act accordingly.

If this story impacted you, if you felt rage, sadness, or hope, leave a comment.

Tell me, was Gideon Parker a murderer or a freedom fighter? Was his violence justified, or was it just more brutality in a brutal world? Do you know other stories of enslaved healers, rebels, and resistors? Share them.

These stories were suppressed for a reason.

Telling them is an act of resistance.

Subscribe to this channel if you believe history should be told honestly without sanitization.

Share this video with someone who needs to hear it.

And never forget the people who built America were not the plantation owners.

They were the enslaved people who survived despite everything.

Honor their memory by continuing their fight for justice.

Until we are all free, none of us are

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load