In April 1859, Bogard Whitmore made an announcement that shocked even the crulest plantation owners in Louisiana.

He had purchased a slave for $3,000, the tallest ever sold in New Orleans, 7’7 in of muscle and scars, an investment that would pay for itself in one harvest.

The White Society of St.

Mary Parish had no idea what was coming.

They had no idea what Josiah would do in the hours that followed.

By midnight, 13 men were dead.

Magnolia plantation was nothing but ashes, and Josiah had disappeared into the swamp like smoke.

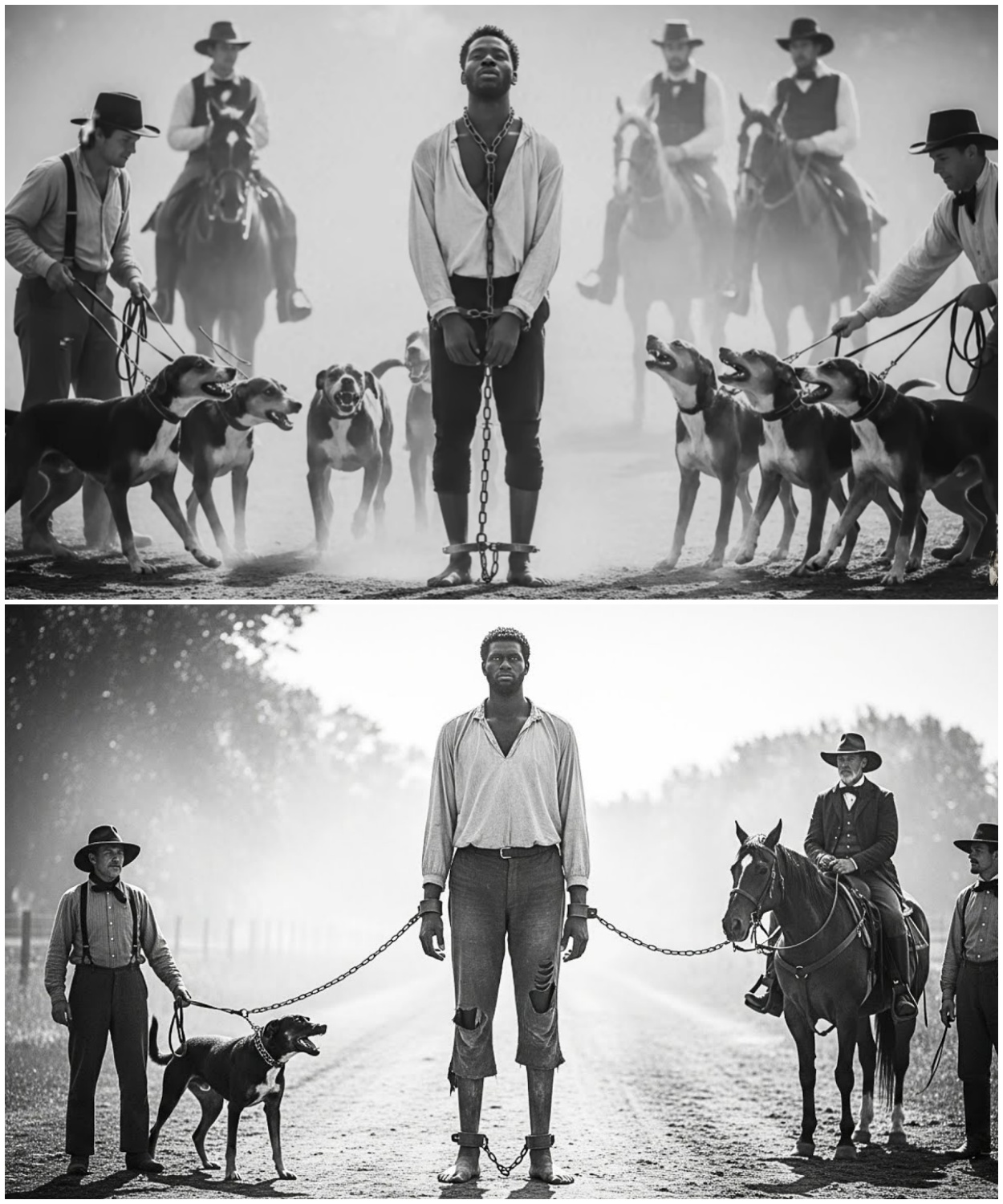

The dust rose and clouds around the horses.

The sun beat down mercilessly on the dirt road that cut through Louisiana swamp land like a scar.

Six white men rode in formation, all armed to the teeth.

black hats stained with sweat, leather suspenders stretched over cotton shirts, rifles strapped across their backs, revolvers at their hips.

These were hard men.

Men who’d spent their lives enforcing the peculiar institution with whips and chains and casual violence.

Men who believed themselves masters of the universe, righteous in their dominion over other human beings.

In the center of the road, walking was a black man.

But calling him simply a man didn’t capture the reality.

He was a giant 7 ft 7 in of solid muscle and scarred flesh.

The chains on his wrists and ankles weren’t the standard iron used for transporting slaves.

These had been specially forged, commissioned specifically for him.

Each link was twice as thick as normal.

The metal gleamed dullly in the afternoon sun, and with each step they produced a rhythmic clinking sound that echoed through the humid air.

More than 40 lb of iron wrapped around his body.

Enough weight to slow any normal man to a crawl.

But this man walked steadily, his pace never faltering, his breathing never labored.

His name was Josiah.

Seven dogs circled him as he walked.

These weren’t house pets or hunting companions.

They were slave dogs, massive animals bred specifically for tracking and attacking runaway slaves.

Blood hounds mixed with mastiffs, creating beasts that combined the tracking ability of one with the fighting power of the other.

Four dogs ranged on his left side, three on his right.

They barked continuously, a cacophony of aggression and barely restrained violence.

teeth bared, revealing yellowed fangs, drool dripping from their jaws onto the dry Louisiana earth.

Their handlers kept them on short leashes, but the dogs strained constantly, wanting to attack, wanting to tear into flesh.

They’d been trained their entire lives for this purpose.

Trained to hate, trained to destroy, trained to associate the scent of black skin with violence and reward.

Bog regard Whitmore rode at the head of the convoy.

He was a fat man, his considerable bulk straining the seams of his expensive clothes.

Sweat poured down his round face soaking into his collar.

But despite his discomfort in the heat, he was smiling.

A broad, satisfied smile of a man who believed he’d made the deal of the century.

$3,000, more than most plantation owners made in a year, more than he could really afford if he was being honest with himself.

But when you were trying to impress the right people, when you were trying to secure your place among the elite, cost became secondary to statement.

And Josiah was one hell of a statement.

Riding just behind Josiah was Tucker, the overseer, the enforcer, the man who turned Whitmore’s orders into reality through liberal application of the whip.

Tucker was lean and hard, all sineu and gristle, his body carved down to its essential components by years of brutal work under the southern sun.

A jagged scar ran from his left eyebrow down across his cheek to his jaw.

a souvenir from a slave who’d fought back 5 years ago.

That slave had lost both hands for his resistance.

Tucker had made sure of it personally.

The scar was a reminder, a badge, proof that Tucker had looked death in the face and survived.

Tucker’s hand never strayed far from the bullwhip coiled at his waist.

12 ft of braided leather stained dark with old blood.

He’d broken a hundred slaves with that whip.

Made strong men weep.

Made proud men beg.

The whip was an extension of his will.

A tool of absolute power.

And right now, more than anything, Tucker wanted to use it on Josiah.

Wanted to see if this giant could be broken like all the others.

Wanted to establish dominance to make it clear from the very beginning who was master and who was property.

Tucker spat a stream of tobacco juice onto the ground.

The brown liquid landed near Josiah’s feet.

Then Tucker pulled the whip from his belt.

The leather uncoiled with a practiced flick of his wrist.

He raised his arm.

The whip cracked through the air like a gunshot.

The sound was designed to intimidate, to provoke a reaction.

Fear, submission, acknowledgment of power.

Josiah didn’t react, didn’t flinch, didn’t turn his head, didn’t alter his steady pace, nothing.

As if the whip hadn’t made a sound at all, Tucker’s jaw tightened.

He cracked the whip again, closer this time.

The leather tip snapped just inches from Josiah’s ear, close enough that any normal man would have jerked away instinctively.

But Josiah kept walking.

Same rhythm, same pace, eyes forward.

Tucker felt something unfamiliar crawl up his spine.

Something he hadn’t felt in years.

Uncertainty, maybe even a flicker of fear.

This wasn’t normal.

Slaves were supposed to react to the whip, supposed to show fear, supposed to demonstrate that they understood the natural order of things.

But this giant walked as if Tucker didn’t exist, as if the whip was nothing.

as if the chains and dogs and armed men were merely inconvenient details rather than instruments of absolute control.

That’s when Josiah stopped walking.

Simply stopped.

No warning, no indication.

One moment he was moving, the next he was stationary.

The dogs lost their minds.

The sudden change in pattern triggered their attack instincts.

They lunged against their leashes, barking so furiously that flex of foam flew from their mouths.

The handlers struggled to control them, digging their heels into the dirt, using all their weight to keep the animals from breaking free.

Tucker’s horse reared slightly, startled by the commotion.

The other men immediately raised their rifles, fingers moving to triggers, eyes wide with sudden alertness.

Whitmore turned his horse around, his smile evaporating, replaced by confusion and the first hints of concern.

Josiah turned his head slowly, deliberately, like a predator deciding whether something is worth its attention.

He looked directly at Tucker and Tucker saw something in those eyes that made his blood run cold.

It wasn’t anger.

Anger he could understand.

Anger was what slaves felt, and anger could be beaten out of them.

It wasn’t fear, either.

Fear was what they were supposed to feel, and fear kept them compliant.

What Tucker saw was something far more disturbing.

It was patience.

The infinite patience of something that knows exactly what it’s going to do and knows that nothing can stop it.

The patience of someone who has waited years for this moment and can wait a few hours more.

The patience of destiny unfolding according to plan.

Tucker’s hand, the one holding the whip, trembled slightly.

He told himself it was from the exertion of holding his horse steady.

Told himself it was the heat.

Told himself it was anything other than what it actually was, which was fear.

Pure primal fear of something he didn’t understand.

For a long moment, maybe 10 seconds, that felt like an hour, Tucker and Josiah stared at each other.

Master and slave, oppressor and oppressed, the natural order of things.

Except in that moment, Tucker didn’t feel like the master.

He felt like prey.

Then Josiah turned his head back forward and started walking again.

Same pace, same rhythm, as if nothing had happened.

Tucker lowered the whip.

Didn’t crack it again.

Didn’t try to assert dominance.

Some instinct deeper than ego told him that using the whip on this man would be a mistake, maybe a fatal one.

He coiled the leather back onto his belt and rode in silence, his eyes never leaving Josiah’s back, his mind working through implications he didn’t want to acknowledge.

They walked for two more hours.

The sun climbed higher, turned the world into a furnace.

Heat shimmerred off the road in visible waves.

The men drank from cantens, wiped sweat from their faces, adjusted their clothing to try to find some relief.

The dogs panted heavily, their tongues loling out, their earlier aggression tempered by exhaustion.

But Josiah never slowed.

Never showed any sign of discomfort.

Didn’t sweat despite the chains and the sun and the relentless pace.

Didn’t breathe heavily.

didn’t stumble or falter.

He walked like a machine, tireless and inevitable.

Tucker watched him obsessively, studied every detail, trying to find some weakness, some flaw, some indication that this was just a man after all.

But the more he watched, the more disturbed he became.

Normal slaves showed wear.

Their shoulders slumped, their steps shortened, their heads drooped.

Even the strongest eventually displayed fatigue.

But not Josiah.

If anything, he seemed to gain strength as they traveled.

His posture remained perfect.

His stride remained measured.

His head stayed level, eyes fixed on some distant point only he could see.

Around midday, Witmore called for a rest stop.

They were near a small creek, a tributary feeding into the larger swamp system.

Shade trees offered some relief from the brutal sun.

The men dismounted gratefully, their legs stiff from hours in the saddle.

They led their horses to the creek to drink, then dropped to the ground themselves, pulling out food from their saddle bags, salt pork, hard bread, some dried fruit.

They ate and talked in low voices, discussing the road ahead, the plantation, normal things that helped them pretend this was just another day of work.

The dogs were released from their leashes, but kept nearby.

They immediately ran to the creek, lapping up water desperately, then collapsed in the shade.

Even their trained aggression had limits.

Even they needed rest.

Josiah was left standing in the full sun, still chained, no water offered, no rest permitted.

Standard procedure for transporting a new slave.

You didn’t give them comfort, didn’t show weakness, established from the very beginning that they were property, not people, that their needs didn’t matter, that their suffering was irrelevant.

Josiah stood, didn’t sit, didn’t seek shade, didn’t show any sign of thirst or fatigue, just stood there in the chains in the sun, motionless as a statue.

Tucker watched him from the shade while chewing on a piece of salt pork, watched and wondered, “How was this possible? Even the strongest men needed water, needed rest, needed relief from the sun.

But this giant stood as if he just started walking.

As if the journey had cost him nothing, as if the chains weighed nothing.

One of the other men, a young overseer named Clayton, noticed Tucker’s attention.

He followed Tucker’s gaze to Josiah, then back to Tucker.

“Something wrong with him?” Clayton asked around a mouthful of bread.

Tucker shook his head slowly.

“Don’t know, but there’s something.

Can’t put my finger on it.

Clayton squinted at Josiah.

He’s just big, probably dumb as a rock like most of them.

Strong back, weak mind.

That’s what makes them good workers.

Tucker didn’t respond.

He’d heard that line a thousand times.

Had probably said it himself a thousand times, the comforting lie that slave owners told themselves.

that the people they owned were somehow less than human, less intelligent, less feeling, more like animals that could be worked and beaten and sold without moral consequence.

But looking at Josiah, Tucker didn’t see anything dumb, didn’t see anything weak, saw something that made every instinct he’d developed over 30 years of slave driving scream warnings he didn’t want to hear.

Whitmore approached Tucker while wiping sweat from his face with an expensive handkerchief.

We making good time.

Tucker nodded.

Should reach Magnolia by nightfall.

If we don’t hit any problems? Whitmore glanced at Josiah.

Think he’ll give us problems? Tucker considered the question.

The honest answer was yes.

Every fiber of his being said yes.

But saying that to Whitmore, who’ just spent $3,000, who was expecting validation of his brilliant purchase, wouldn’t go over well.

So Tucker said, “He’s been compliant so far, but I’d keep close watch on him.

There’s something about him that ain’t right.

” Whitmore laughed.

“You’re getting superstitious in your old age, Tucker.

He’s just a big negro.

Strong as an ox, sure, but still just property.

Nothing mysterious about it.

Tucker wanted to argue, wanted to explain the feeling in his gut, the way Josiah had looked at him, the unnatural endurance, the complete lack of fear.

But he knew how it would sound, like an old man getting spooked by shadows.

So he kept quiet and finished his meal.

30 minutes later, Whitmore gave the order to move out.

The men mounted their horses.

The dogs were leashed again and Josiah resumed his walk.

They had roughly six more hours to Magnolia Plantation.

6 hours that would change everything.

6 hours that would end with blood and fire and screams.

But nobody knew that yet.

Nobody except possibly Josiah.

3 days earlier, the scene had been very different.

The French Quarter of New Orleans hummed with activity.

The slave market on Ru Royale was packed as it was every Tuesday and Friday.

Hundreds of people moved through the space.

White men in expensive suits examining merchandise.

Traders shouting about the qualities of their stock.

Auctioneers working the crowd into bidding frenzies.

And slaves.

Dozens of slaves standing on wooden platforms displayed like livestock.

Their bodies exposed for inspection, their humanity stripped away by the casual cruelty of commerce.

Families were being separated.

A mother pulled away from her children, sold to one buyer while her babies went to another.

The woman screamed, reached desperately for her children.

The children cried, not understanding why mama was leaving, why these strange white men were taking her away.

The traders didn’t care.

This was business.

Sentiment was bad for profit.

You couldn’t sell a family unit for as much as you could sell individuals.

So, you separated them, maximized returns.

The screaming was just background noise.

Something you learned to ignore after a while.

But on this particular day, the usual chaos of the market paused when they brought out lot 47, the giant.

Word had spread through the quarter over the past two days.

The tallest slave ever brought to New Orleans, a specimen that had to be seen to be believed.

Traders came from as far as Mobile and Nachez just to witness the auction.

Plantation owners who hadn’t planned to buy anything showed up out of curiosity.

Even some of the wealthier free people of color came to watch, though they stayed at the back, careful not to draw attention.

It took six men to bring Josiah onto the platform.

Not because he resisted.

He walked calmly, cooperatively, but because the platform steps weren’t built for someone his size.

They had to modify the positioning, adjust the chains, figure out how to display him properly.

When they finally got him situated, standing at the center of the platform, a collective murmur ran through the crowd.

He was enormous.

Pictures and descriptions hadn’t done it justice.

7′ 7 in of solid muscle.

Shoulders as wide as a door frame.

Arms as thick as most men’s legs.

Hands that looked like they could crush skulls.

And yet, despite the massive size, he wasn’t clumsy or disproportionate.

Everything was in proportion.

Like someone had taken a normal man and scaled him up by 50%.

A giant from old stories.

something that shouldn’t exist but did.

The auctioneer was a man named Dearoo, a veteran of 30 years in the trade.

He’d sold thousands of slaves in his career.

He knew every trick, every technique to drive up prices, but even he seemed momentarily aed by Josiah.

Dearu climbed onto a wooden crate so he could be at roughly eye level with his merchandise.

He gestured grandly at Josiah while addressing the crowd.

Gentlemen, in my three decades of service, I have never, and I mean never, seen anything comparable to what stands before you today.

This magnificent specimen comes directly from the heart of Africa.

Pure Angolan stock, a warrior from a tribe that produces the finest physical examples of the Negro race.

All lies, of course, but effective lies.

Exotic origin always commanded premium prices.

Deur continued his pitch.

Observe the muscular development, the perfect health, the scars of a warrior.

This is not some field hand who will break down after a few years.

This is an investment that will pay dividends for decades.

One slave with the productivity of five normal men.

Imagine what he could do for your operation.

The crowd pressed closer, craning their necks to get a better view.

Some of the planters whispered to their associates, calculating, evaluating, determining if the potential return justified what would obviously be a significant expenditure.

Tucker had been there.

He’d accompanied Whitmore to New Orleans specifically to evaluate potential purchases for Magnolia.

They’d spent two days looking at various slaves, examining teeth and muscles, checking for signs of disease or rebelliousness.

Whitmore was in the market for maybe three or four good field hands.

Nothing fancy, nothing expensive, just solid workers to replace some who died over the winter.

But when they heard about the giant, curiosity got the better of them.

They showed up at the auction expecting to watch, not to bid.

Devo opened the bidding at $500, a strategically low number to get people engaged.

Multiple hands went up immediately.

Within two minutes, the price had climbed to a,000, then 1,200, 1,500, 2,000.

The bidding slowed.

That was serious money, more than most planters spent on five slaves combined.

But a few determined buyers remained.

a Mississippi planter named Garrett, a Texas rancher named Hullbrook, and Bo Regard Whitmore.

Tucker had grabbed Whitmore’s arm when the price hit 2,000.

Sir, that’s too much.

We can’t afford it.

But Whitmore shook him off.

You don’t understand.

This isn’t about money.

This is about status.

About proving I belong.

Tucker didn’t understand then.

Didn’t know about the brotherhood.

Didn’t know about Whitmore’s desperate need to solidify his position among the parish’s elite.

Didn’t know that Whitmore had already overstretched his finances to join the secret society and now felt pressured to demonstrate his commitment.

At $2,500, the Texas rancher dropped out.

At 2,800, the Mississippi planter reluctantly bowed out.

Only Witmore remained.

Devo looked at him expectantly.

2800 is the current bid.

Will you go higher? Whitmore hesitated.

Tucker could see him calculating, weighing risks against rewards.

Then Witmore raised his hand.

$3,000.

The crowd gasped.

$3,000 for a single slave was unheard of.

Insane.

Financial suicide.

Devaroo waited, looking around for any counter bids.

None came.

He struck his gavvel three times.

Sold to Mr.

Bogard Whitmore of Magnolia Plantation.

Tucker watched the other planters, saw their expressions.

Some showed disbelief.

Some showed contempt for such fiscal irresponsibility, but others, particularly the ones Tucker knew belonged to the brotherhood, showed something different.

approval, respect.

Whitmore had just demonstrated he was willing to spend beyond reason to make a statement, that he valued reputation over practical concerns, that he was truly one of them.

Tucker didn’t know the details of the brotherhood then, just knew that Whitmore attended secret meetings, that he’d become obsessed with impressing certain people, that his behavior had become increasingly erratic over the past year.

After the sale, paperwork was completed, bills of sale drawn up, money exchanged.

Tucker stood nearby while clerks processed the transaction.

He noticed an old slave chained near Josiah.

The old man was weeping, not quietly, loud, racking sobs.

Another slave nearby asked him what was wrong.

The old man responded in a language Tucker didn’t recognize, some African dialect, but the tone was unmistakable.

It was a warning or a lament.

The other slave looked at Josiah with new eyes, with fear, with something like reverence.

Then both old slaves looked away quickly as if afraid that too much attention would draw consequences.

Tucker filed that moment away, told himself it was nothing, just superstitious nonsense.

Slaves were always finding reasons to be afraid, always seeing omens and signs.

It didn’t mean anything.

But the image stuck with him.

The old man crying.

The other slave’s expression of fear and Josiah standing calm and still through it all.

Never reacting, never acknowledging, just waiting with that infinite patience.

The transaction completed.

Whitmore approached Josiah for the first time as owner.

Tucker accompanied him.

Whitmore looked up at the giant, having to crane his neck at an uncomfortable angle to make eye contact.

Do you understand English? Josiah’s voice was deep, resonant, like distant thunder.

Yes, master.

The words were clear, properly pronounced.

No slave dialect.

That was unusual.

Most slaves either didn’t speak English well or deliberately mangled it as a small form of resistance.

But Josiah spoke like an educated man.

Whitmore seemed pleased.

Good.

That will make things simpler.

You belong to me now.

You will work on my plantation.

You will do as you’re told.

If you work hard and obey, you’ll be treated fairly.

If you cause problems, you will be punished severely.

Do you understand? Yes, master.

Whitmore nodded, satisfied.

He pulled out a cigar, lit it, and blew smoke in Josiah’s direction.

A casual assertion of dominance.

I paid a fortune for you, more than you’re probably worth, but I believe in investing in quality.

Don’t make me regret it.

” Josiah said nothing.

Whitmore waited, perhaps expecting some expression of gratitude, some acknowledgment of how fortunate Josiah was to have such a benevolent owner.

When none came, Witmore frowned.

“Well, don’t you have anything to say?” Josiah met his eyes, held the gaze longer than any slave should, long enough that Tucker’s hand moved instinctively toward his whip.

Then Josiah spoke.

I understand, master.

I will do exactly what I was brought here to do.

Something about the phrasing bothered Tucker.

Not what was said, but how it was said.

the emphasis on certain words as if Josiah was talking about something beyond simple labor, but Witmore seemed to miss it.

He smiled, took the response as appropriate deference.

Good.

We leave at dawn tomorrow.

Get some rest.

You have a long walk ahead of you.

Then Whitmore and Tucker left to find lodging for the night.

behind them.

Josiah remained chained to the platform, standing in the darkness as the market closed down around him.

Standing and waiting, always waiting.

That night, in the slave pens beneath the market, something happened that nobody recorded officially, but stories about it spread through the slave community.

Whispered tales that traveled from plantation to plantation over the following weeks.

The story said that Josiah had spoken to the other slaves in the pen, had told them things about what was coming, about plans that had been set in motion years ago, about debts that would soon be paid.

Some of the stories claimed he spoke in tongues, African languages mixed with English mixed with something older, something that made the words feel like they had physical weight.

One story said that Josiah told them his real name.

That Josiah was just another slave name, another piece of identity stripped away by white men who couldn’t be bothered to remember African names.

The story said his true name translated roughly as the one who returns.

Another story claimed that Josiah bore marks on his body, scars that formed patterns, symbols from the old religions, marks that identified him as something special, a warrior, a priest, an avenger sent by ancestors to balance accounts.

Tucker heard these stories later, dismissed them as typical slave superstition, but he remembered them.

Remembered and wondered.

Now, 3 days later, riding through the Louisiana heat, watching Josiah walk with that inhuman endurance, Tucker wondered if maybe there was something to those stories after all.

Maybe not literally.

He didn’t believe in magic or spirits or any of that nonsense.

But maybe metaphorically, maybe this giant really was different, special, dangerous in ways that went beyond physical size.

Maybe Whitmore had bought something that couldn’t be owned, something that would destroy them all.

Tucker shook his head, trying to dislodge the thoughts.

Fear was weakness.

Doubt was weakness.

He was an overseer.

He controlled slaves through certainty and violence.

He couldn’t afford to question, couldn’t afford to wonder.

But the thoughts remained.

They reached the swamp proper around midafter afternoon.

The road narrowed, squeezed between encroaching wetland on both sides.

The air grew heavier, thick with humidity and the smell of rotting vegetation.

Cypress trees rose from murky water, their branches draped with Spanish moss that hung like gray curtains.

The light changed, filtered through the canopy, turning everything dim and greenish.

This was dangerous country, not just from natural hazards like alligators and snakes, but from human threats.

Runaway slaves lived deep in these swamps.

Maroon communities that had existed for decades, communities of people who’d escaped bondage and carved out hidden lives in places no white man could easily reach.

The plantation owners called them criminals, thieves who’d stolen themselves, but they couldn’t eliminate them.

The swamps were too vast, too complex.

Attempts to raid the maroon camps usually ended badly.

Men went into the swamp and didn’t come back or came back changed, traumatized by what they’d encountered.

So an uneasy balance existed.

The maroons stayed deep.

The planters stayed out, and occasionally the maroons raided, stealing supplies, helping other slaves escape, reminding the white establishment that their power had limits.

As they entered this territory, the men became more alert.

Rifles were unslung, held ready, eyes scanned the treeine constantly.

Even the dog sensed the change, their ears pricricked forward, low growls rumbling in their chests.

This was not their territory.

This was a place where the normal rules didn’t apply, where white supremacy was a claim rather than a fact.

Whitmore rode closer to the group, his earlier confidence tempered by awareness of genuine danger, but Josiah seemed completely at ease.

If anything, he appeared more relaxed than he had on the open road.

His eyes tracked left and right, taking in details of the landscape.

His lips moved slightly, as if he was counting or cataloging.

Tucker noticed and felt that crawling sensation on his spine again.

It was the look of someone surveying familiar ground, someone who knew this place.

But that was impossible.

Josiah had supposedly just arrived from Africa via a slave ship to Cuba, then transferred to a New Orleansbound vessel.

He’d never been to Louisiana before, had no reason to recognize this swamp, yet he moved through it like he was coming home.

Then they heard it.

Distant at first, so faint that several minutes passed before everyone consciously registered the sound.

Drums, rhythmic beating carried on the heavy air.

African drums playing patterns that spoke to something primal.

The white men shifted nervously in their saddles.

Drumming from the swamp meant the maroons were active, were watching, were possibly preparing something.

Whitmore called out orders.

Tighten up.

Stay alert.

Keep moving.

Don’t stop for anything.

The pace increased.

The horses moved faster.

The dogs were pulled closer.

Everyone wanted to get through this section quickly, get back to open ground where they could see threats coming.

Everyone except Josiah.

His pace didn’t change.

same steady rhythm he’d maintained all day, which meant the group had to slow down to match him or drag him, which would be difficult given his size in the terrain.

They slowed down and the drums got louder.

Not dramatically, not like they were getting closer to the source, more like additional drums were joining in, creating layers of sound, complex poly rhythms that seem to come from multiple directions simultaneously.

It was disorienting, impossible to pinpoint where the drummers actually were.

Tucker had heard maroon drums before.

Every overseer in Louisiana had.

But these were different.

More organized, more purposeful, like they were communicating specific information rather than just making noise, like they were coordinating something.

Tucker’s grip tightened on his rifle.

“Mr.

Whitmore,” he called out.

We should consider turning back.

Find another route.

Witmore’s face was pale, sweat pouring down despite the shade of the canopy.

But he shook his head.

This is the only route to Magnolia from here.

Going back means losing half a day.

We go forward.

Just stay sharp.

That’s when they reached the bridge.

It appeared suddenly around a bend in the road.

a wooden structure spanning a section of swamp where the water was particularly deep and dark.

The bridge was old, maybe 50 years, constructed when this road was first established.

It had been repaired many times, patched and reinforced, but it was still fundamentally a fragile thing, narrow, only wide enough for one horse at a time.

The planks were weathered gray, gaps visible between them where you could see down to the water below.

And in that water, shapes moved.

Long, dark shapes that drifted just beneath the surface.

Alligators.

Lots of them.

Alligators were common in Louisiana swamps.

Seeing a few around a bridge was normal, but this was different.

Tucker counted at least 20 visible animals, probably more hidden in the murky water.

They weren’t moving naturally, weren’t hunting or basking or doing typical alligator things.

They were positioned, arranged in a rough circle around the bridge, waiting as if they’d been called there, as if they were expecting something.

Whitmore stared at the scene.

What in God’s name? One of the other overseers, a man named Perkins, spoke up.

It ain’t natural.

Gators don’t school up like that.

Something’s wrong.

Tucker agreed.

Every instinct screamed at him to turn around, find another way.

But Whitmore was right about the time.

Going back meant adding hours to their journey, meant traveling in the dark, meant possibly camping in the swamp overnight.

All bad options.

We cross, Whitmore decided one at a time.

Careful.

Test each plank before putting full weight on it.

If the bridge holds, we’re through this in 10 minutes.

He went first, demonstrating leadership, showing courage.

Even though Tucker could see his hands shaking on the rains, Witmore’s horse stepped onto the bridge carefully.

The planks creaked but held.

Slowly, Witmore crossed, reached the other side safely, called back.

It’s solid.

Come on.

Two more riders went, then another.

Each crossing seemed to take forever.

The drums continued their complex rhythms.

The alligators continued their unnatural waiting, and Josiah stood at the edge of the bridge, watching everything with those patient eyes.

Finally, it was time for the rear group to cross.

Tucker, Perkins, one other overseer named Davis, and Josiah.

The dogs would cross with their handlers.

Tucker gestured with his rifle.

You’re next.

Move.

Josiah stepped onto the bridge.

The structure groaned under his weight.

The chains added mass, but the first few steps seemed fine.

Josiah reached the midpoint of the bridge, then stopped.

Just stopped like he’d done on the road earlier.

Tucker shouted, “Keep moving.

Don’t stop in the middle.

” But Josiah didn’t move.

He stood there looking down at the water, at the alligators.

Then Josiah did something that stopped Tucker’s heart.

He began to hum low and deep, that voice that sounded like distant thunder.

The tune was strange.

Nothing Tucker recognized.

Not European.

Not any slave song he’d heard.

Something older.

Something that seemed to resonate in the bones rather than the ears.

And the alligators reacted.

They began to move.

Not toward the bridge.

Not attacking, just moving in patterns, circling, rising partially out of the water, opening their jaws wide, showing teeth that could crush bone like twigs.

Stop that,” Tucker screamed.

“Whatever you’re doing, stop it.

” But Josiah continued.

The humming grew slightly louder.

The alligator’s movements grew more agitated.

Then Josiah spoke, words that weren’t English, weren’t any language Tucker recognized.

Guttural sounds that seemed to vibrate the very air.

And one of the alligators surged partially out of the water, its massive body propelling itself upward, jaws snapping at the underside of the bridge just feet from where Josiah stood.

The bridge shook, planks splintered.

But Josiah remained perfectly balanced, unmoved by the chaos he’d created.

Perkins panicked.

His horse had been next in line to cross.

The animal, already spooked by the drums and the alligators, completely lost its composure when the bridge shook.

It reared.

Perkins, a decent rider under normal circumstances, wasn’t prepared.

He lost his seat, fell backward, his boot caught in the stirrup for a moment, leaving him hanging.

But then his momentum tore him free.

He fell, not onto the bridge, into the water beside it.

The dark water filled with 20 alligators that had been waiting for exactly this moment.

Perkins surfaced, gasping, disoriented.

He had maybe 2 seconds of life left.

Tucker saw his face, saw the realization hit, saw the scream form.

Then the water erupted.

Multiple alligators surged toward the thrashing man simultaneously.

The first jaws closed on his leg.

Perkins screamed, a sound of pure agony and terror.

He tried to grab onto something, anything, but there was nothing to hold.

Another alligator hit him from the side, then another.

The water churned red pieces.

That was all Tucker’s mind could process.

Perkins was being torn into pieces.

The screaming stopped after maybe 10 seconds.

The thrashing continued a bit longer.

Then nothing, just disturbed water slowly settling, red foam drifting and the alligators sinking back down, sated, their purpose fulfilled.

Josiah chose that moment to continue walking.

Stepped off the far end of the bridge.

Stood on solid ground on the other side, Tucker and Davis, both frozen in horror, snapped back to awareness.

They spurred their horses, crossed the bridge faster than was safe, planks cracking under them.

But they made it.

Got to the other side, got away from that cursed water.

The dogs followed, nearly dragging their handlers in their desperation to get across.

On the far side, the entire convoy had stopped.

Everyone stared back at the bridge, at the water where Perkins had died.

Whitmore’s face was ashen.

What happened? What the hell just happened? Tucker couldn’t speak.

His throat was closed.

His mind kept replaying the moment.

Josiah humming.

Josiah speaking those words.

The alligators responding.

Perkins falling.

The feeding frenzy.

Was it all connected or just horrible coincidence? Tucker wanted desperately to believe it was coincidence.

But he couldn’t.

Not after everything else he’d seen.

Not after feeling that inhuman patience in Josiah’s eyes.

Tucker looked at Josiah.

The giant stood quietly, showing no emotion, no satisfaction, no remorse, nothing.

Just that eternal waiting.

Tucker rode up to him, put the rifle barrel against Josiah’s chest.

His finger trembled on the trigger.

You did that? I don’t know how, but you did that.

You killed Perkins.

Josiah looked down at him, spoke in that deep voice.

Did I? I stood on a bridge.

A man fell from his horse.

Alligators did what alligators do.

Where is my crime? The words were perfectly reasonable, perfect logic.

But the tone, the tone suggested something else entirely.

suggested complicity, suggested that yes, he’d absolutely killed Perkins and there wasn’t a damn thing anyone could do about it.

Whitmore rode between them.

Tucker, stand down.

It was an accident.

A terrible accident, but an accident.

Perkins’s horse spooked, that’s all.

Tucker wanted to argue, wanted to explain what he’d seen and heard.

But looking at Witmore’s face at the desperation there, Tucker realized that Whitmore couldn’t afford to believe anything else.

Whitmore had spent $3,000 on this slave, had staked his reputation on this purchase.

Admitting that the slave was dangerous, was possibly responsible for Perkins’s death, would mean admitting catastrophic error.

would mean financial and social ruin.

So Whitmore would believe the lie, would force everyone else to believe it, would punish anyone who suggested otherwise.

Tucker lowered his rifle.

Yes, sir.

An accident.

My mistake.

But his eyes promised Josiah something.

Promised that this wasn’t over.

That he was watching.

That at some point, somehow there would be a reckoning.

Josiah met his gaze and smiled.

Not a big smile, just a slight upward curve at the corners of his mouth.

But that small smile contained volumes, contained acknowledgement and anticipation and absolute certainty about how this story would end.

Then Josiah turned and continued walking toward Magnolia Plantation, toward destiny, toward blood and fire and the settling of accounts that had been building for years.

They were five men now instead of six.

Five men, seven dogs, three horses, and still 3 hours from the plantation.

Three hours that passed in tense silence.

The drums had stopped after the bridge.

The swamp grew quieter as they progressed, but somehow the silence was worse than the sound had been.

It felt expectant, like the swamp itself was holding its breath, waiting to see what would happen next.

Tucker rode near the front now, as far from Josiah as possible, while still maintaining his responsibilities.

He kept his rifle across his lap, ready to fire, kept looking back over his shoulder to check where the giant was.

Every time he looked, Josiah was there, walking steadily, never tiring.

Those chains that should have slowed him down seemed like nothing.

Tucker found himself thinking about legends.

Stories passed down from his grandfather’s time.

Stories about slaves who were more than human, who had powers, who could call animals, who could curse people, who could see the future.

Tucker had always dismissed those stories as fairy tales designed to frighten children.

But now he wondered, “What if some of it was true? What if there were people who existed outside normal rules? What if Josiah was one of them?” Tucker shook his head violently, trying to dislodge the thoughts.

This was the heat, the stress, the shock of watching Perkins die.

It was making him irrational.

Josiah was just a man, a big man with unusual endurance, sure, but still just a man made of flesh and blood.

Still vulnerable to bullets and chains and the normal instruments of control.

Still just property that could be mastered.

Tucker repeated this to himself like a prayer, like if he believed it hard enough, it would become true.

The sun was setting when they finally emerged from the swamp proper.

The land opened up, transitioned from wetland to agricultural fields.

Rice patties stretched in geometric patterns, their standing water reflecting the orange sky.

Groups of slaves worked in the fields, bent double, hands in the water, harvesting the grain that made men like Witmore wealthy.

The slaves didn’t look up as the convoy passed, didn’t acknowledge the arrival of a new captive, kept their eyes down, kept working because that was survival.

But Tucker noticed some of them.

Noticed how their bodies tensed slightly.

Noticed how the rhythm of their work stuttered for just a moment, as if they felt something, as if they knew something had changed.

Magnolia Plantation’s main buildings appeared ahead.

The big house stood on a slight rise, white columns gleaming in the dying light.

Around it clustered the various structures that made a plantation function.

Slave quarters, overseer houses, barns and storage buildings, a blacksmith shop, cotton gins, the rice processing facility.

Everything arranged to maximize efficiency, to extract maximum labor from the hundreds of enslaved people who lived and died here.

Witmore’s kingdom, his pride, his investment, his future.

They rode through the main gate.

Guards there recognized Witmore and opened the heavy wooden doors without question.

The convoy moved into the central courtyard, a large open space where various plantation business was conducted, where slaves were punished, where announcements were made, where new slaves were processed and branded, where later that night everything would burn.

Whitmore dismounted, his face showing relief at finally reaching home.

He stretched, working out the kinks from hours in the saddle.

Get him processed,” he told Tucker.

“Brand him.

Get him assigned to quarters.

We’ll start him in the fields tomorrow.

” Tucker nodded and began organizing.

Four guards came to assist, men with rifles and clubs.

The seven dogs were kept close, still aggressive despite their exhaustion.

They surrounded Josiah in a loose circle.

Tucker gestured toward the center of the courtyard where the branding equipment waited.

Abrasure already glowed hot, maintained constantly for this purpose.

Iron rods with Witmore’s initials BW heated in the coals, ready to mark flesh to permanently identify property.

On your knees, Tucker ordered.

Josiah looked at him for a long moment, then slowly, deliberately lowered himself to the ground.

The guards moved in closer.

Two grabbed his arms, holding them outstretched.

Another grabbed his head, forcing it down, exposing his upper back.

A fourth began unlocking the chains around his wrists.

Standard procedure.

You couldn’t brand through the chains.

Had to remove them temporarily.

Of course, with six armed men and seven attack dogs surrounding him, there was no risk.

A slave kneeling held by guards couldn’t possibly be a threat, right? The blacksmith, a burly white man named Collins, pulled one of the branding irons from the brazier.

The tip glowed white hot.

He approached Josiah, raised the iron, prepared to press it into the flesh between shoulder blades.

It should have been a routine procedure.

Collins had done this hundreds of times, but as he moved the iron closer, something happened.

Josiah raised his head slightly, not throwing off the guard who held him, just lifting enough to make eye contact with Collins.

And Collins saw saw whatever Tucker had seen, whatever the old slave at the auction had seen, whatever truth lived behind those eyes.

Collins froze.

The iron trembled in his hand.

Sweat poured down his face, but not from the heat of the metal, from pure irrational terror.

His mouth opened and closed soundlessly.

The iron slipped from his grip, fell to the dirt, lay there glowing and smoking.

Collins stumbled backward.

His knees buckled.

He fell to a sitting position.

Started making sounds that weren’t quite words.

Whimpering, crying, praying all at once.

The guards holding Josiah looked at each other in confusion.

What’s wrong with him? Tucker rushed over to Collins.

What happened? What did you see? But Collins couldn’t articulate it.

Could only point at Josiah with a shaking hand and make those sounds of existential dread.

Tucker looked from Collins to Josiah and back.

Someone else brand him, he shouted.

now.

But none of the other guards moved.

They’d all seen Collins’s reaction.

All felt the same unease they’d been trying to ignore all day.

None of them wanted to get close to that giant.

None of them wanted to look into those eyes.

That’s when they heard it.

The first scream high and piercing coming from somewhere outside the courtyard walls from the direction of the slave quarters.

Then another scream and another.

A chorus of screams rising into the twilight air.

Not screams of pain, screams of something else.

Liberation, rage, declaration, the sound of chains breaking, of patience ending, of accounts being settled.

Tucker ran to the courtyard wall, climbed the wooden stairs to the top where guards normally patrolled, looked out across the plantation.

What he saw made his mind refuse to process it initially.

Torches, hundreds of torches moving through the fields, emerging from the swamp, coming down the access roads, surrounding the plantation completely.

And carrying those torches were people, black people, slaves from Magnolia, slaves from neighboring plantations, maroons from the deep swamp, all converging on this spot.

All moving with purpose, all armed with whatever they could carry.

Axes, machetes, clubs, farm implements turned into weapons.

Tucker’s breath caught in his throat.

This was impossible.

Slave rebellions didn’t happen like this.

Didn’t involve hundreds of people.

Didn’t show this level of organization.

Didn’t announce themselves with such brazen confidence.

This was every plantation owner’s nightmare made manifest.

This was the thing they feared in their darkest moments.

The thing they built their entire system to prevent, and it was happening right now, right here.

Whitmore joined Tucker on the wall, went pale when he saw the torches.

Jesus Christ, how many? Tucker tried to count, gave up.

200, maybe three, maybe more.

Whitmore’s voice climbed toward panic.

Where did they come from? How did they organize this? Tucker knew the answer.

Knew, but didn’t want to say it.

Didn’t want to acknowledge what should have been obvious from the beginning.

Finally, he forced the words out.

Him.

Josiah.

This is his doing.

Has been from the start.

They both turned to look back at the courtyard at the giant who still knelt on the ground, surrounded by guards who’d forgotten they were supposed to be controlling him.

Josiah raised his head, looked directly up at Tucker and Witmore on the wall, and smiled fully for the first time, a smile of satisfaction, of victory, of destiny fulfilled.

Then casually, as if it required no effort at all, Josiah tensed his arms.

The chains on his wrists, already loosened by the guards, snapped like thread.

The metal links forged to hold the strongest slave, exploded apart.

Pieces flew in different directions, striking the ground with sharp pinging sounds.

The guards jumped back, releasing him, reaching for weapons, but they were too slow.

Confused, frightened.

Josiah rose to his full height, 7 ft 7 in of controlled power.

He reached down and grabbed the chain still attached to his ankles.

Pulled.

The metal shrieked in protest, then snapped.

Just like the wrist chains, just broken.

Impossible, but real.

Josiah stood completely unrestrained for the first time since Tucker had seen him.

Stood free.

One of the guards raised his rifle, aimed at Josiah’s chest.

His hands shook so badly that the barrel wavered.

Don’t move.

Don’t you dare move.

Josiah turned to face him.

Didn’t attack.

Didn’t charge.

Just looked at the guard with something like pity.

You should run, Josiah said quietly.

All of you should run while you still can.

The guard’s finger tightened on the trigger, but before he could fire, the courtyard gates exploded inward.

The heavy wooden doors, reinforced with iron, designed to withstand assault, shattered as if they were made of paper.

The first wave of rebels poured through.

20 people, 30, 50, all moving fast, all with weapons raised, all with years of suppressed rage finally given outlet.

The guards turned to face this new threat, started firing their rifles.

The shots were deafening in the enclosed space.

Some rebels fell, but not enough.

There were too many.

They swarmed over the guards like a wave.

Clubs rose and fell.

Machetes swung.

Screams filled the air.

Both sides, attackers and defenders.

The careful order of the plantation dissolved into chaos.

Tucker watched from the wall in horror.

This couldn’t be happening.

Couldn’t be real.

But it was.

The evidence was right in front of him.

His world ending in blood and fire.

Whitmore grabbed his arm.

We need to get to the house.

We can defend there.

We have more guns, more men.

They ran down from the wall, tried to reach the big house, but rebels were everywhere, pouring into the courtyard, spreading through the plantation, methodical and determined, not random violence, organized action.

Tucker and Whitmore made it perhaps 20 yards before they were cut off.

Five rebels blocked their path.

men Tucker recognized.

Slaves who’d worked magnolia fields for years, who’d seemed docile, broken, accepting of their place.

But their eyes now held something very different.

Held all the hatred and pain and loss that they’d carefully hidden for years.

Held justice long delayed.

Whitmore pulled out a pistol, shot one rebel in the chest.

The man went down, but the others didn’t stop.

didn’t even slow.

They came forward.

Tucker swung his rifle like a club.

Connected with someone’s head.

Felt the impact.

Felt bones break.

But then hands grabbed him from behind.

Strong hands.

Too many hands to fight off.

He went down.

Felt fists and boots.

Felt pain exploding through his body.

He tried to curl up.

Tried to protect himself, but the blows kept coming.

Relentless, merciless.

The same mercilessness he’d shown slaves for 30 years coming back to him now.

Balance being restored, accounts being settled.

His last conscious thought was of Josiah, of those patient eyes, of that smile.

And he understood finally what he’d been too blind to see from the beginning.

This had never been about one slave.

Had never been about one plantation.

It was bigger, much bigger.

A movement, a coordinated uprising that had been planned for years.

And Josiah had been the key, the catalyst, the spark that lit the fire.

Whitmore had thought he was buying a slave.

Had actually bought his own destruction.

Everything that happened next happened fast, but felt like it lasted forever.

The rebels swept through Magnolia Plantation with devastating efficiency.

The guards outnumbered and outfought fell one by one.

The overseers who’ dispensed cruelty so casually discovered what it felt like to be on the receiving end.

Some died fighting.

Some died begging.

All died knowing why.

Knowing what they’d done to earn this.

Knowing that the system they’d upheld had created the very people who would destroy them, the big house went up in flames first.

Someone threw a torch through a window.

The expensive curtains caught immediately.

Fire spread through the dry wood structure faster than anyone could have stopped, even if they’d wanted to, which they didn’t.

The rebels watched it burn and cheered.

That house had represented their bondage, had been built with their labor, had housed the man who owned them like property.

Seeing it burn was liberation made visible.

The other buildings followed, barns, stables, storage sheds, the slave quarters.

Everything burned.

The rebels had decided to leave nothing.

to make Magnolia Plantation cease to exist, to erase it so completely that future generations would barely remember it had been here.

Fire was purification.

Fire was judgment.

Fire was justice.

In the chaos, Josiah moved calmly.

He wasn’t directly participating in the violence.

Wasn’t killing anyone personally.

That wasn’t his role.

His role had been to organize, to plan, to bring all these people together, to give them hope that resistance was possible, that they could win.

He’d done his job.

Now he let others do theirs.

He walked through the burning plantation like a ghost, observed, remembered, made sure certain things were done correctly.

One task remained, the most important one.

Josiah went to Whitmore’s office in the big house.

Flames were already eating through the walls, but the office itself hadn’t caught yet.

Inside, in a hidden safe behind a painting, were documents, the Brotherhood’s records, a ledger containing 40 years of meeting notes, names of members, descriptions of rituals, details about victims, the kind of evidence that could destroy the most powerful families in Louisiana, evidence that had to be preserved.

Josiah opened the safe, took the ledger, also took Whitmore’s personal journals, letters from other Brotherhood members, anything that documented their crimes.

He wrapped these carefully in oil cloth, protected them from the fire, from water damage, from time.

These documents would serve a purpose.

Not now, but eventually when the moment was right, when they could do maximum damage, Josiah would make sure they survived, would make sure the truth couldn’t be buried completely.

With the documents secured, Josiah left the burning house, walked through the courtyard where bodies lay scattered, guards, overseers.

Whitmore himself recognizable despite the damage.

Josiah looked down at the man who’d bought him, felt nothing, no satisfaction, no remorse, just completion.

This particular account was closed.

But there were 12 more Brotherhood members in St.

Mary Parish, 12 more men who’d participated in the rituals, who’d murdered innocent people, who believed themselves untouchable.

Over the next two weeks, every single one of them died.

Not all at once, not all in the same way, but systematically, methodically.

The maroons handled most of it.

They’d been waiting for this opportunity for years.

Finally had leadership that could coordinate action.

Finally had someone who understood both the slave world and the white world.

Someone who could plan operations that actually succeeded.

Judge Pelum died in what appeared to be a hunting accident.

Reverend Krenshaw’s house burned down with him inside.

Banker Lyall disappeared on a business trip.

His body never found.

On and on.

The white population of St.

Mary Parish panicked.

Called for military intervention, demanded protection.

But they couldn’t explain why they were being targeted.

Couldn’t reveal the Brotherhood without destroying themselves.

So they invented stories about random violence, about northern agitators, about slave rebellions that had to be crushed.

The newspapers printed these lies.

The officials repeated them, and gradually the truth was buried under layers of convenient fiction.

Josiah left Louisiana a month after the uprising, traveled north using the routes he’d spent years planning.

The maroons helped him get out of the state, provided guides, safe houses, everything he needed.

He crossed into free territory in Ohio.

From there went to Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, where he could live as a free man, where he could build a new life, where he could work openly with abolitionists instead of secretly with maroons.

He changed his name, took the surname Freeman because it represented what he’d become.

Josiah Freeman.

It had a nice sound.

He found work, legitimate work that paid actual wages, married a free black woman named Rebecca, had children, three boys, raised them in freedom, taught them to read and write, taught them about their heritage, about Africa, about slavery, about resistance, about the cost of freedom and the importance of preserving it.

But Josiah never forgot.

never let himself forget why he’d come north, why he’d survived when so many others hadn’t.

He kept the Brotherhood’s documents hidden, protected them, occasionally showed them to trusted abolitionists, used them as evidence of slavery’s horrors, as proof that the system wasn’t just about economics, was about something darker, something that turned men into monsters, something that had to be destroyed completely.

When the Civil War started in 1861, Josiah was 43 years old, too old to fight officially, but he helped anyway.

Worked with the Underground Railroad, helped escaped slaves reach safety, provided intelligence about plantation layouts, about which owners were vulnerable, about where to strike for maximum effect.

He was still fighting, still settling accounts, just using different methods.

He lived to see slavery abolished.

Lived to see the Confederacy defeated.

Lived to see the beginning of reconstruction.

Saw black men vote for the first time.

Saw black children attend schools.

Saw the first generation born into freedom instead of bondage.

It wasn’t perfect.

Wasn’t anywhere close to true equality.

But it was better.

Was progress.

Was proof that change was possible.

when people refused to accept the intolerable.

Josiah Freeman died in 1899 at age 81.

His funeral was attended by hundreds of people, black and white, people whose lives he’d touched, people he’d helped, people who knew his story and understood what he represented.

The newspapers wrote about him, called him a respected community member, a successful businessman, a family man.

All true, but incomplete.

They didn’t know about Magnolia Plantation, about the uprising, about the Brotherhood’s destruction.

That part of his story died with him.

Or did it? His children knew some of it.

His grandchildren heard stories.

Fragments passed down through generations.

And the documents still existed, hidden carefully, but existing, waiting to be found, waiting to tell their story.

Maybe one day someone would discover them, would piece together the truth, would understand what really happened in St.

Mary Parish in 1859.

Or maybe not.

Maybe the legend was enough.

Maybe the whispered stories were more powerful than documented facts.

What we do know is this.

Magnolia plantation burned completely on the night of April 15th, 1859.

23 white men died.

Bogard Whitmore, Tucker the Overseer, guards and overseers whose names were recorded.

Over a 100 slaves disappeared that night, vanished into the swamp, officially listed as runaways.

Most were never recovered.

The plantation was never rebuilt.

The land was sold off piece by piece, eventually became farmland.

Then in the 20th century, housing developments.

Today, you’d never know what happened there.

No marker, no monument, just suburban streets and normal houses where families live normal lives.

But the swamp remembers the black water and cypress trees.

Remember on certain nights when the wind blows right, when the moon is dark, people claim to hear things.

Drums, voices, the clinking of chains, screams, fire crackling.

Some say it’s the spirits of those who died, still fighting their battle, still settling accounts.

Others say it’s just the wind, just the natural sounds of the swamp, just imagination filling darkness with meaning.

I’ll leave you to decide.

Was Josiah just a man, unusually large, unusually strong, but fundamentally human? Or was he something more? a force, a reckoning, an answer to prayers spoken by millions of enslaved people over centuries.

Did he plan and execute a brilliant military operation? Or did he tap into something deeper, something older, something that bent reality itself toward justice? The truth probably lies somewhere in between.

Josiah was human.

But humans, when pushed far enough, when organized effectively, when fighting for their freedom, can accomplish things that seem impossible, can overthrow systems that seem permanent, can defeat enemies that seem invincible.

That’s not magic.

That’s not supernatural.

That’s just what happens when people refuse to accept their oppression.

when they find leaders worth following, when they coordinate action instead of suffering alone.

The story of Josiah and Magnolia Plantation is one small chapter in a much larger story.

The story of resistance, of people fighting back against injustice, of the enslaved refusing to accept their enslavement.

That story happened thousands of times across the South, in small ways and large.

in successful rebellions and failed ones, in secret escapes and open confrontations.

Most of those stories were never recorded, were deliberately erased.

But they happened and they mattered.

They accumulated over time, built pressure until eventually the entire system collapsed under the weight of its own evil.

So remember this, history belongs to those who tell it.

For too long, the story of American slavery was told by the enslavers, by people who wanted to minimize the horror, who wanted to pretend it was benevolent, who wanted to erase the resistance.

But the truth always finds a way out, always bubbles up through the carefully constructed lies.

Stories like Josiah’s remind us that enslaved people weren’t passive victims.

They were active resistors.

They fought, they planned, they won.

Not always, not easily, but they fought.

And that legacy matters today.

Matters for every person fighting against oppression.

Matters for everyone told they’re powerless, told they should accept injustice, told that the system can’t be changed.

Josiah’s story says otherwise.

says that careful planning, patience, organization, and courage can topple even the most entrenched power.

Says that justice, even when delayed, can still come.

Says that the ark of the moral universe, as someone once noted, bends toward justice, but it doesn’t bend on its own.

People like Josiah bend it.

What do you think about this story? Do you believe it happened? Do you think Josiah was real? Or is this just a legend, a myth designed to inspire? Leave your thoughts in the comments.

Tell me if you’ve heard similar stories.

If your family passed down tales of resistance.

These stories need to be remembered, need to be told, need to be kept alive so future generations understand that freedom has always been fought for, has never been given freely, has always required courage and sacrifice, and people willing to stand up and say enough.

If you enjoyed this deep dive into dark history, subscribe to the channel.

Turn on notifications so you never miss a story.

Share this with someone who appreciates history.

That doesn’t sanitize the past.

That doesn’t make it palatable.

That tells the truth even when it’s uncomfortable.

Until next time, remember, the past isn’t past.

History isn’t dead.

The stories we tell shape the present and the future.

Choose your stories carefully.

Tell the truth.

Remember those who fought so we could be here.

and keep fighting for justice because the work is never finished.

Until next video.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load