For more than a century, the wedding portrait sat undisturbed, reproduced in books, cataloged in ledgers, passed over by scholars who saw in it nothing more than a proper Victorian union.

A man seated with confidence, a woman standing at his side, respectability frozen in silver salts.

It was not until 2024 when the photograph was removed from a sealed private collection in Springfield, Illinois, that anyone thought to truly look at it, not as a symbol, but as evidence.

The photograph arrived on the desk of archival image analyst Marian Clark on an overcast February morning, still mounted in its original cardboard frame.

The date pencled faintly on the back read 1899.

The subjects were identified in tiny cursive Henry Walters and Lilian Moore.

Marian had handled thousands of wedding portraits from this era, sepiaoned rituals of compliance and expectation, and at first glance this one offered no resistance to that familiar reading.

Henry Walters sat in a carved studio chair, shoulders squared, his jaw set with the ease of a man accustomed to being obeyed.

His suit was dark, well-tailored, expensive.

One hand rested on his knee, the other hooked casually over the armrest, signaling ownership not only of the furniture, but of the moment itself.

Standing beside him was Lillian Moore, dressed in immaculate white, her bodice tightly fitted, her veil arranged with precision.

Her face was composed, almost serene, the faintest suggestion of a smile trained into place.

Everything about the image spoke the language of order.

Marian scanned it anyway.

High resolution magnification had become second nature to her.

A discipline born of years spent studying what time tries to erase.

Fabric fibers, background scratches, the involuntary truths that survived despite the photographers’s intent.

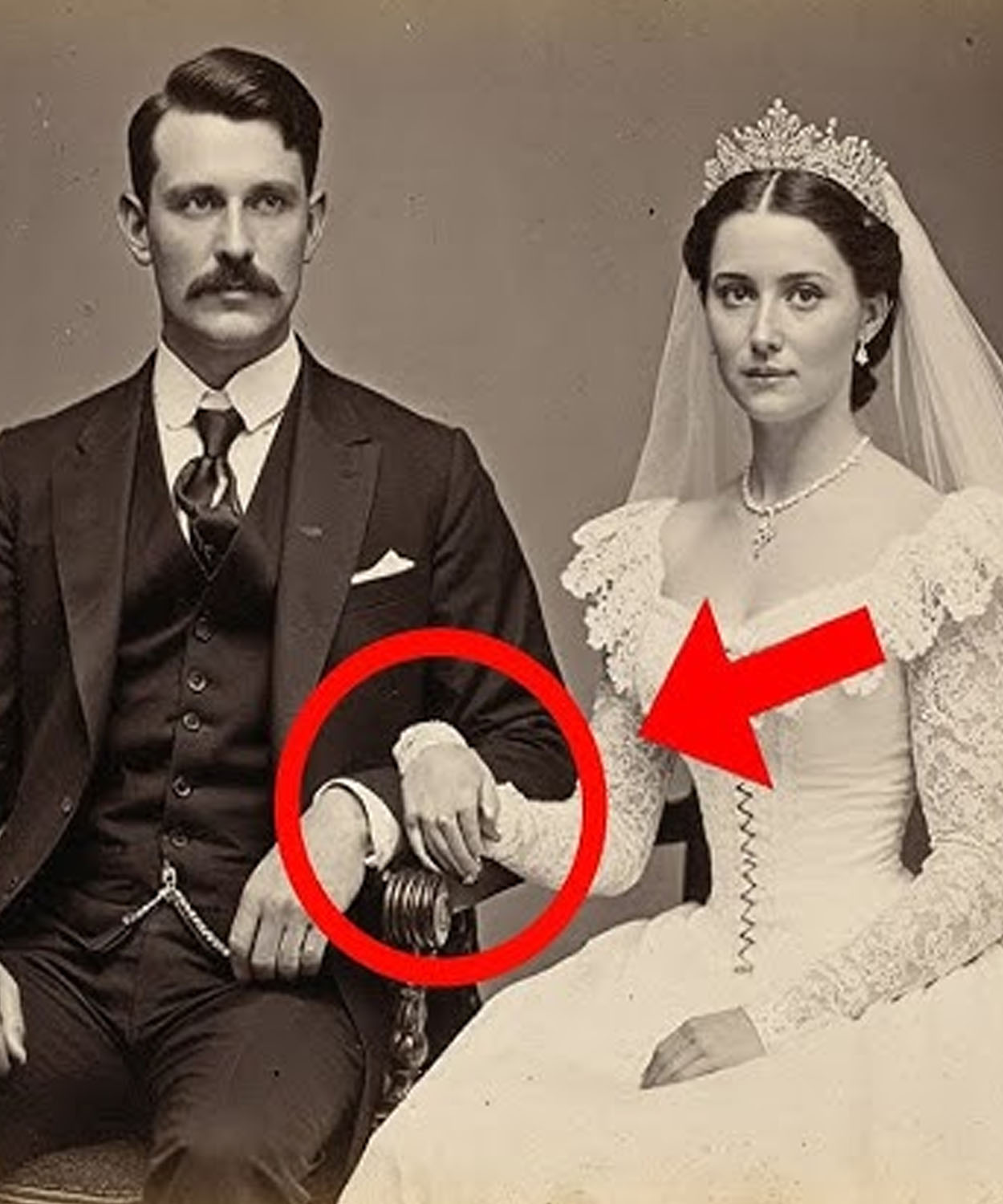

She enlarged the image incrementally, drifting from Henry’s polished boots to the careful pleading of Lillian’s skirt.

That was when she stopped.

Lillian’s left hand was partially hidden in the folds of her dress just below the waistline.

It was not resting.

It was not relaxed.

The fingers were bent at sharp, deliberate angles, the muscles visibly tense beneath the skin.

This was not the idle placement of a nervous bride, nor the stiff accident of long exposure.

It was held.

Marion adjusted the contrast.

Zoomed closer.

The thumb pressed inward.

The index finger extended slightly apart from the others.

The remaining fingers curled with restraint as if resisting a tremor.

Marian felt a familiar chill that came when an image stopped behaving like an image and began to behave like a message.

Victorian portraiture demanded stillness.

Poses were instructed, corrected, and forced.

Any deviation, especially in a wedding photograph, was risky.

unseemly.

And yet this hand had been positioned with intent maintained through the long seconds required for exposure.

Someone had told Lillian how to stand, where to look, how to present herself.

But this this was hers.

Marian pulled reference guides from her shelf, period manuals on posture, gesture, and photographic etiquette.

None accounted for this configuration.

The more she compared, the clearer it became that the hand did not belong to the language of celebration.

It belonged to something else.

She sat back from the screen, the room suddenly too quiet.

Outside the archive windows, traffic moved without consequence.

The present indifferent to what had just surfaced from the past.

Marian understood then that the photograph was not incomplete.

It was interrupted.

The anomaly was not a flaw.

It was a signal small, dangerous, and easily ignored, and for 125 years, it had been.

Marian did not trust solitary conclusions.

Photographs, she believed, only surrendered truth when interrogated by more than one discipline.

Within 48 hours, she arranged a consultation with Professor Jonathan Reed, a historian whose work focused on late 19th century social customs and non-verbal communication.

Reed had spent decades reconstructing how bodies were trained to behave in public, how posture, clothing, and gesture were used to enforce hierarchy long before a word was spoken.

They met in a quiet university archive room, the air heavy with the smell of aging paper and dust.

Marion placed a large print of the photograph on the table between them.

Reed studied it in silence for several minutes, his expression tightening not at the faces, but at the space between them.

This is not a casual image, he said.

Finally.

Wedding portraits in 1899 were among the most controlled visual rituals in American society.

Every detail mattered.

He explained that photographers of the period often followed rigid scripts.

Brides were instructed to display modesty without weakness, obedience without fear.

Hands, in particular, were carefully managed.

A woman’s fingers were expected to rest softly, either folded or lightly touching a prop.

Tension was forbidden.

Any strain suggested impropriy, illness, or resistance, things no respectable family wanted immortalized.

Reed leaned closer, tracing the outline of Lillian’s hidden hand with his finger, careful not to touch the paper.

This position would have been uncomfortable to hold, he said.

It requires intention and more importantly it requires defiance.

Someone told her how to pose.

She chose not to comply fully.

Their first hypothesis formed slowly, reluctantly like something neither wanted to name.

Perhaps the bride had been nervous.

Perhaps she was signaling anxiety, discomfort, cold.

Reed dismissed these almost immediately.

Anxiety produced tremors, not structure.

cold caused clenching, not articulation.

This was deliberate, practiced, and meaningful.

In 1899, Reed continued, “Marriage was not merely a personal contract.

It was a legal transfer of authority.

Once married, a woman’s financial identity, residence, and autonomy effectively ceased.

If a woman believed she was being forced into that transfer, she had almost no lawful recourse.

” Marian asked the question hanging between them.

Would there have been a way for her to ask for help? Reed hesitated.

Then he nodded.

There were unofficial systems, he said.

Mostly oral, rarely documented.

Women, particularly those trapped by family pressure or economic dependence, sometimes used silent signals, gestures small enough to evade male supervision, but recognizable to other women.

midwives or reform-minded observers.

These signals were dangerous.

Being discovered could result in institutionalization, confinement, or worse.

That risk was precisely why they were subtle and why they were forgotten.

Their working theory became darker with each layer of context.

If Lilian Moore had believed herself coerced, the wedding portrait was not commemorative.

It was evidentiary.

a single moment where she still possessed control over her body before the law stripped it from her.

Marian searched municipal records that same week.

Census roles, church registries, local newspapers from Springfield and surrounding counties.

Henry Walters appeared intermittently.

Business listings, a property transfer, a brief mention in a railroad investment circular.

Lilian Moore did not.

There was no marriage certificate filed under her name, no recorded change of residence, no death notice, no scandal, no allotment, no burial.

Within weeks of the photograph’s date, she vanished from official documentation entirely as though the woman in the image had never legally existed.

Reed was the one who articulated what both had beg to suspect.

If the marriage was real, he said quietly, there would be paperwork.

If it was false, staged or incomplete, then the photograph becomes something else entirely, not a record of union.

But a warning issued from the narrow space between legality and disappearance.

And if that was true, then the image had captured Lilian Moore not at the beginning of her life as a wife, but at the precise moment before she was erased.

The breakthrough came not from a marriage archive or a courthouse ledger, but from a book that was never meant to survive.

Marian found it in a restricted university collection, an 1897 etiquette guide printed in a limited run for women’smies and private finishing schools.

Its title was deceptively harmless, a manual on comportment and discretion, bound in fading blue cloth.

Most of its pages were predictable sermons on posture, modesty, and silence.

But near the back, almost as an afterthought, was a chapter that did not belong.

It addressed what the author called circumstances of personal peril.

The language was careful, euphemistic, designed to avoid scandal.

It acknowledged, without naming, the existence of situations in which a woman might be constrained by familial or social authority and denied the ability to speak freely.

In such cases, the guide proposed a system of discrete bodily signals, hand positions, finger tensions, minor deviations from approved poses.

They were described not as rebellion, but as appeals, messages meant to be read by those trained to notice.

Marian felt her pulse quicken as she compared the illustrations to the scanned photograph.

One gesture, in particular, matched with unsettling precision.

The guide described it as rare, reserved for situations of imminent loss of autonomy.

The thumb pressed inward.

The index finger extended slightly apart.

The remaining fingers drawn tight.

The meaning was printed plainly without embellishment.

I am being held against my will.

The room seemed to contract around her.

This was not speculative symbolism or modern projection.

It was period accurate, documented.

deliberate.

Lillian Moore’s hand, hidden in the folds of her wedding dress, had formed a sentence.

Marian and Reed returned to the archives with renewed urgency.

If Lillian had known this signal, she had been educated beyond the average expectations of women in 1899.

That narrowed the field.

School records showed Aillian Moore enrolled briefly at a women’s commercial institute in Illinois trained in shorthand bookkeeping and clerical work.

A stenographer, literate, observant, precisely the kind of woman who might encounter information not meant for her.

Then came the absences.

There was still no marriage license, no church bands, no announcement in society columns.

That alone was unusual.

Victorian weddings, even modest ones, left paper trails.

But more troubling was what happened after the photograph.

City directories listed Lilian Moore at a boarding house address until late summer of 1899.

Then her name disappeared, not crossed out, not amended, simply gone.

Employment records from a railroad linked financial firm showed her on payroll through July of that year.

In August, her wages were collected by a proxy.

In September, her position was marked vacated.

No reason given.

No forwarding address.

Henry Walters, by contrast, continued to appear everywhere.

Property transactions, business partnerships, travel notices.

He moved freely through the public record, unencumbered by explanation.

The imbalance was unmistakable.

One subject expanded.

The other collapsed.

The photograph’s timing became impossible to ignore.

It was taken after Lillian had already beg to vanish, but before the erasure was complete.

A narrow window in which she was still visible enough to leave something behind.

The more Marion studied the image, the more she noticed what had once seemed benign.

The way Henry’s body angled slightly toward Lillian, not affectionate, but possessive.

The chair anchoring him firmly while she stood unsupported.

The absence of wedding rings.

The studio backdrop chosen not for romance, but for neutrality.

Everything suggested control disguised as propriety.

This was no documentation of a beginning.

It was a record made under supervision.

Lillian had known what was happening.

She had known the limits of speech, the dangers of resistance, and so she used the only space left to her, a fraction of a second, a gesture small enough to pass unnoticed by the man beside her, yet precise enough to survive a century.

The photograph did not capture a bride.

It captured a woman mid-signal, marking the moment when her disappearance had already began, but was not yet irreversible.

With the signal identified, the photograph ceased to be a mystery and became a timeline.

Marian and Reed turned away from symbolism and toward reconstruction, assembling the weeks surrounding the image with the precision of a crime scene analysis.

What emerged was not a sudden disappearance, but a controlled narrowing of Lilian Moore’s life.

Employment records revealed her position as a stenographer at a financial firm with deep ties to regional rail expansion.

These firms were not merely clerical operations.

They were conduits of power, handling land speculation, bond issuances, and quiet transfers of capital that shaped entire towns.

Stenographers, though officially invisible, saw everything.

Contracts passed through their hands before they were signed, numbers before they were legitimized.

In late June of 1899, Lillian had been assigned to transcribe a series of internal ledgers outside her normal duties.

The pages concerned land parcels near a proposed rail spur properties purchased under false names, then resold at inflated values once routes were announced.

It was not innovative business.

It was fraud and it involved men whose influence extended well beyond Springfield.

One memo preserved only because it was misfiled noted that Miss Moore has asked unnecessary questions.

Another written in a different hand recommended that the matter be handled discreetly.

That was where Henry Walters entered the story.

Contrary to the photograph’s implication, Henry was not a groom in any conventional sense.

He appeared in private correspondence as a resolver, a man employed to smooth problems that could not reach courtrooms.

His work required no official title, only trust from the right people.

He specialized in transitions, removing individuals from situations without producing scandal bodies or documentation.

The solution, as they conceived it, was elegant.

Marriage offered immediate social cover.

A woman could leave her employment without suspicion.

Her residence could change without inquiry.

Her absence from public life could be explained as domestic adjustment, and once legally bound, her testimony, if it ever surfaced, would be easily dismissed as hysteria, grief, or marital dissatisfaction.

The wedding portrait was staged quickly.

No guests, no church, no license filed, just an image sufficient to imply legitimacy if questions arose later.

Lillian was dressed, instructed, positioned.

The appearance of consent was mandatory.

What they did not anticipate was her resistance.

The photograph was taken in early July.

Within days, Lillian’s boarding house room was vacated by others.

Her belongings were removed by men not listed in any directory.

Her bank account was closed.

The balance withdrawn by authorization she could not have signed while employed.

By August, her name existed only in internal correspondence and even there it began to be replaced with euphemisms.

She has been settled.

The matter is concluded.

There was no record of travel.

No ticket purchased.

No destination named.

Lilian Moore did not flee.

She was transferred quietly under the authority implied by a marriage that never legally occurred.

Reed framed it carefully when he spoke.

This was not murder, he said.

It was something more efficient.

She was rendered unreachable.

Marian returned again to the image.

Henry’s expression now read differently, not celebratory, but vigilant, a man overseeing a process.

Lillian’s face, trained into calm, carried the subtle vacancy of someone aware that time had shortened.

Her signal had not been impulsive.

It had been calculated.

She knew this photograph might be the last moment she was seen by anyone who knew her name.

The tragedy was not confined to her disappearance.

It extended into the structure that allowed it.

A system where marriage could function as erasure, where legality could be implied without being filed, where a woman’s intelligence became a liability requiring containment.

Lilian Moore’s life was not ended publicly.

There was no body, no grave, no scandal to satisfy outrage.

She was absorbed into silence.

Her autonomy dissolved under the appearance of respectability.

All that remained was a single image taken after the danger began and before the final door closed, bearing the quiet defiance of a woman who understood exactly what was being done to her and chose with the last control she possessed to leave a mark.

The confirmation arrived from a place no one expected to yield truth.

The accounting books of a long-defuncted photography studio.

Marian located them in a municipal storage facility mislabeled as theater receipts, their leather spines cracked, their pages warped by humidity.

The studio, operating under a forgettable surname and a main street address, had specialized in formal portraiture for clients who preferred discretion over publicity.

The wedding portrait was there, not as a celebration package, not under the names Henry Walters or Lilian Moore.

The ledger entry was clinical, almost evasive, one large format plate, neutral backdrop, no retouching, paid in full, in advance, and paid for by a third party.

The name attached to the payment was not unfamiliar.

It appeared in the same railroad linked financial correspondence Lillian had transcribed months earlier.

A silent partner, an intermediary, someone with no public reason to commission a wedding photograph for two people he was not related to.

The implication was immediate and devastating.

The portrait had not been ordered by a groom or a family.

It had been commissioned as documentation, proof that a solution had been enacted.

Evidence that could be produced if questions arose or destroyed if they did not.

Marian traced the payment trail backward.

It led through shell accounts, attorney retainers, and temporary offices rented for only weeks at a time.

At the center of it all was Henry Walters, or rather the name Henry Walters, because that too began to unravel.

Census comparisons, travel records, and employment listings revealed inconsistencies impossible to reconcile.

Henry Walters appeared in Illinois in 1899, but a man of the same description, same height, same facial scar, same handwriting had been documented in Missouri 3 years earlier under a different name.

And in Indiana two years before that, each time he surfaced briefly, attached to a woman whose records later collapsed into absence.

The pattern was unmistakable.

Henry Walters was not a person.

He was a role.

Reed described it with restrained disbelief.

He’s a mechanism, an identity passed along or reused.

He exists only where he’s needed then dissolves.

Marriage in these cases was not an institution but a tool.

A socially sanctioned transfer of custody masquerading is romance.

The women involved shared traits that made them vulnerable and valuable.

Education without protection, knowledge without power, proximity to information that endangered men who could not be exposed.

Lilian Moore fit the pattern precisely.

Further confirmation arrived in fragments.

A hotel register bearing Henry’s signature, but no companion.

A notorized affidavit referencing of private domestic matters settled without litigation.

A letter written by a junior clerk years later expressing unease about what became of the stenographer, then abruptly changing subject mid-sentence.

There was no single document that confessed to the crime.

There never would be.

What existed instead was convergence.

Independent records bending toward the same conclusion.

The wedding was false.

The marriage was never legal.

The disappearance was intentional.

Lillian had not been silenced in panic or rage.

She had been processed.

The shock was not that such a system existed.

It was how efficiently it operated without leaving bodies, trials, or outrage.

Respectability did the work violence usually did.

Paperwork replaced force.

And when paperwork failed, identities did.

Marian returned once more to the photograph, now armed with the knowledge of its function.

Henry’s presence was no longer ambiguous.

He was not a husband posing beside his bride.

He was an agent overseeing completion.

The chair, the posture, the angle of his body, all reinforced authority.

The image was composed to suggest permanence.

Lillian’s signal disrupted that illusion.

Against the system designed to erase her cleanly, she introduced noise, a mark that could not be explained away once it was understood.

She had anticipated the possibility, however remote, that someone in the future might notice what contemporaries were trained not to see.

The photograph had not failed in its original purpose.

It had succeeded in another.

It preserved the moment when a woman facing a disappearance engineered to look like a marriage, refused to vanish quietly, and instead embedded the truth in plain sight, trusting time to deliver it to someone willing to look closely enough.

With the mechanism exposed, the photograph no longer invited interpretation.

It demanded reclassification.

What had once been archived as a wedding portrait now belonged to a different category entirely, one rarely acknowledged in institutional collections.

It was evidence produced under coercion, carrying a message never meant for its original custodians.

Marian wrote this plainly in her report.

The photograph is not commemorative.

It is communicative.

every element aligned with that conclusion.

The absence of legal documentation, the third party payment, the manufactured identity of the groom, the timing positioned precisely between professional suspicion and total erasure.

Most damning of all was the gesture itself, not expressive, not emotional, but instructional.

Lilian Moore had not been asking for sympathy.

She had been transmitting information.

The hand mattered more than the face.

Victorian photography trained viewers to read expressions, composure, modesty, joy restrained by propriety.

[bell] That training was part of the deception.

Faces could be coached.

Muscles could be disciplined, but hands, when unobserved, remained the last territory of unsupervised language.

Lillian had exploited that gap with precision.

Her signal did not accuse it.

did not name.

It did not describe.

It simply established condition.

I am being held.

That distinction was crucial.

Accusation invited denial.

Condition demanded investigation.

By choosing a gesture tied to etiquette rather than protest, she ensured the message could survive inside the rules designed to silence her.

Reed framed the realization carefully during their final review session.

This photograph wasn’t meant to save her.

He said it was meant to outlive them.

Lillian had understood the limits of her situation.

She could not escape without triggering pursuit.

She could not speak without being discredited.

She could not refuse the portrait without inviting immediate consequence.

But she could comply imperfectly.

She could introduce a flaw small enough to pass beneath the notice of those who believed the image already belonged to them.

The brilliance and the tragedy was that her strategy required time, decades, perhaps a century.

It depended on the future developing tools and sensibilities her present did not possess.

High resolution scanning.

Archival cross referencing.

A willingness to question respectability itself.

The photograph’s purpose was never to preserve a union.

It was to preserve a contradiction.

A woman presented as a bride who was in fact a detainee.

A marriage image without a marriage.

A gesture hidden in plain sight, betting everything on the possibility that someone someday would look at the wrong detail long enough for it to speak.

Lilian Moore had left no diary, no letter, no final testimony.

She could not ensure her survival, but she could ensure traceability.

The photograph anchored her existence to a specific moment, a specific crime, and a specific system.

It denied her capttors the clean disappearance they intended.

That was the true defiance.

Not resistance in the dramatic sense, but documentation, the refusal to be unrecorded, the insistence that even if her body was removed from the world of records, her knowledge of what was happening to her would remain encoded in one sanctioned image.

The camera meant to legitimize her erasure became its undoing.

And once understood, the photograph ceased to be an object of curiosity.

It became a statement, one that redefined what survival could mean in an era where power operated quietly, efficiently, and without witnesses.

Lillian Moore did not leave behind a memory of herself.

She left behind proof.

The investigation ended the way most historical reckonings do, without resolution, without justice, without bodies to exume or verdicts to overturn.

Lillian Moore was never found.

No death certificate surfaced under her name or any other.

No asylum ledger listed her admission.

No burial record hinted at a quiet interament under an alias.

The system that removed her had been designed precisely to prevent such closures.

Those responsible did not face consequences.

The financiers whose signatures threaded through the ledgers died respected men.

Their estates were settled cleanly.

Their names affixed to buildings, scholarships, and plaques that celebrated progress and enterprise.

The intermediaries vanished into other roles, other cities, other manufactured identities.

Even the studio that captured the photograph dissolved without scandal, its records boxed and misfiled until time dulled their significance.

History absorbed the loss the way it absorbs countless others by smoothing it into absence.

Marian’s final report was accepted quietly.

No press release accompanied its filing.

The photograph was reclassified, moved from the celebratory archive into a restricted collection reserved for coercive artifacts.

It gained new metadata.

Suspected forced marriage, probable disappearance, non-verbal distress signal identified.

Clinical language for an INT asterisk mate destruction.

The image itself did not change.

Henry Walters still sat confidently.

Lilian Moore still stood in white.

But once seen, it could not be unseen.

The silence around it grew heavier, not lighter, because it was now informed silence.

What lingered most was the restraint of Lillian’s final act.

She had not tried to indict the world that was consuming her.

She had not dramatized her suffering.

She had simply marked it, trusting that restraint would give the message longevity, that someone somewhere in the future might care enough to notice the wrong thing.

The photograph remains in an archive today, stored in a climate control drawer, removed from public rotation.

Scholars request access.

Students study it.

Each generation brings sharper tools and broader questions.

And with each enlargement, the same detail asserts itself with greater clarity.

The hand, the tension, the refusal to relax into the lie.

There is no epilogue for Lilian Moore, no discovered letter, no miraculous survival revealed by a census anomaly decades later.

Her story ends where the records end, which is precisely where her capttors intended it to end.

The only reason it did not vanish completely is because she anticipated that outcome and acted accordingly.

That is the final unsettling truth of the photograph.

It does not offer closure.

It does not restore what was taken.

It does not redeem the past.

It stands instead as an accusation directed forward in time, aimed not at those who orchestrated her disappearance, but at those who inherit the archives they curated.

It asks a single question without words.

What else have you mistaken for normal? Sometimes the most horrifying details in old photographs are not hidden by shadows or damage.

They are the ones placed deliberately, patiently, and full view, waiting for a future that is willing to look closely enough to understand what it cost for them to be there.

And once you do, the image never returns to silence.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load