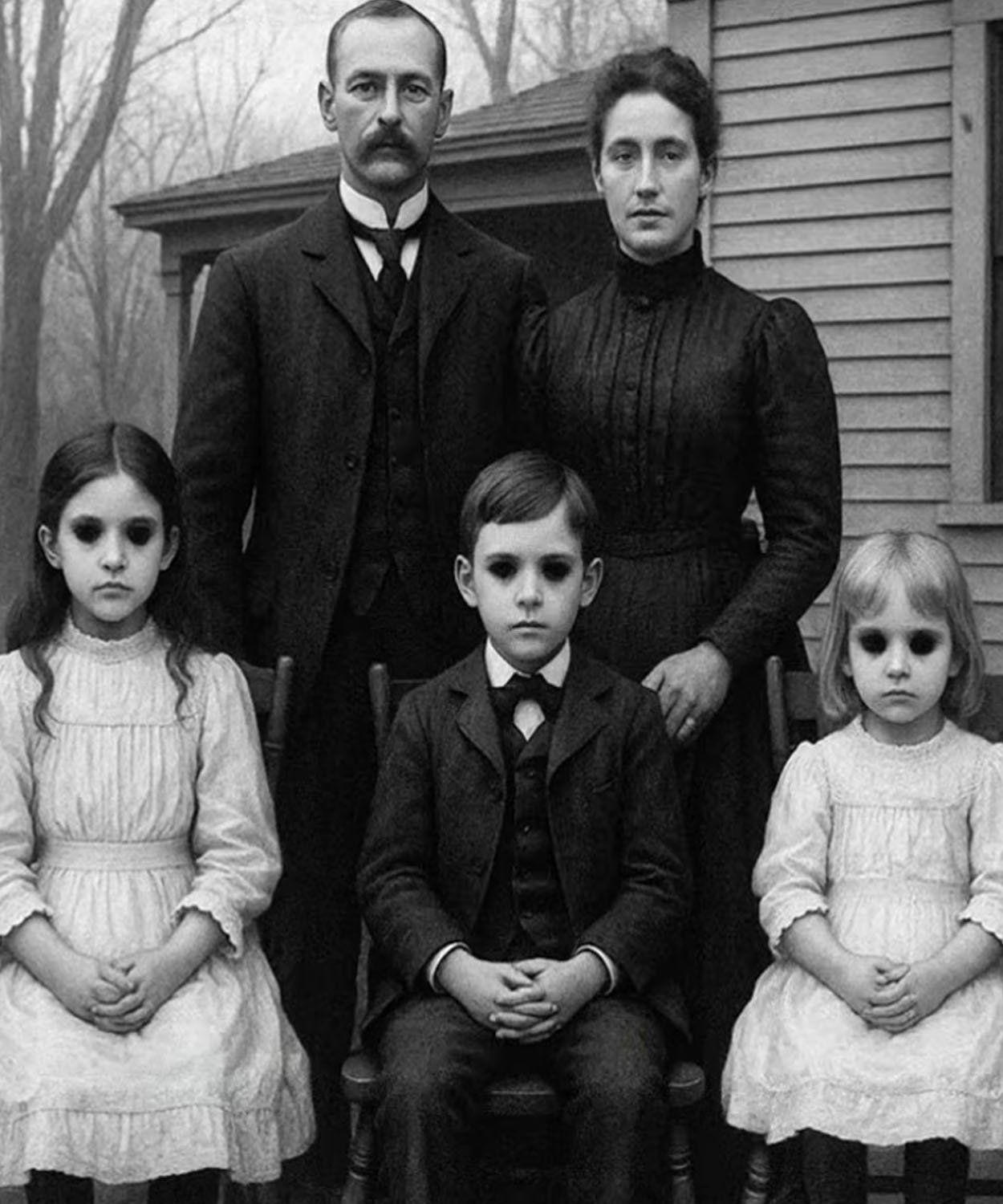

Have you ever looked at an old photograph and felt like something was watching you back? Today, we’re diving into one of the most unsettling discoveries in photographic restoration history.

A portrait from 1902 that hides a detail so disturbing it’s kept researchers awake at night.

Now, let’s step back to a Chris autumn morning in 1902 in the small town of Asheford, Connecticut.

The Harrison family stood outside their modest Victorian home on Maple Street, preparing for what should have been a routine family portrait.

James Harrison, a respected pharmacist in town, stood tall beside his wife, Elellanena, a school teacher known for her gentle manner.

Their three children, Margaret, aged nine, Thomas, aged seven, and little Elizabeth, just 5 years old, were dressed in their Sunday best, starched collars, and pristine white dresses that their mother had pressed the night before.

The photographer, a traveling portraitist named Samuel Witmore, had arrived from Hartford with his large format camera and developing equipment.

In those days, having your photograph taken was a significant event, often marking important family milestones.

The process was expensive, timeconsuming, and required everyone to remain perfectly still for several seconds while the exposure captured their image on glass plate negatives.

Samuel positioned the family carefully.

James and Elellanena stood behind their children, hands resting protectively on their shoulders.

The three children sat in wooden chairs arranged in a precise row, their hands folded in their laps as instructed.

The morning light filtered through the bare branches of the oak trees lining the street, casting dappled shadows across the scene.

Everything about that morning seemed ordinary.

Neighbors later recalled hearing the children’s laughter as they played before the session began.

Mrs.Patterson from next door remembered waving to Elellanena as she coraled the children into position.

The milkman, making his rounds, tipped his hat to James as he passed by.

It was, by all accounts, an unremarkable October day in a quiet New England town.

Samuel took his time setting up the shot.

He adjusted the camera’s position three times, ensuring the composition was perfect.

Elellanena fussed over Margaret’s hair ribbon, tucking a stray curl behind her ear.

Thomas fidgeted until his father’s firm hand on his shoulder reminded him to stay still.

Little Elizabeth, the youngest, seemed the most composed, staring directly at the camera with an expression that Samuel later described in his journal as unnervingly calm for such a young child.

The exposure took approximately 8 seconds.

During that time, nobody moved.

The family held their positions perfectly, a testament to the discipline instilled in children of that era.

When Samuel finally covered the lens and announced they were finished, Elellanena exhaled with relief.

The children immediately returned to their usual energy, running around the yard while their parents discussed payment with the photographer.

Samuel packed his equipment and promised to return within 2 weeks with the finished portrait.

He departed on the afternoon train, his glass plate negatives carefully wrapped and stored in his leather case.

The Harrison family went about their Sunday, attending church services and enjoying a quiet dinner together.

Everything seemed perfectly normal.

The portrait was delivered as promised, beautifully printed and mounted in an elegant wooden frame.

The Harrisons hung it proudly in their parlor above the fireplace where visitors could admire it.

For decades, it remained there, a snapshot of a moment in time.

a family frozen in the formal style typical of the era.

The photograph changed hands many times over the following century.

When Elellanena Harrison passed away in 1954, the house was sold and the portrait ended up in an estate sale.

A local antiques dealer purchased it along with several other items.

From there, it traveled through various collections, flea markets, and antique shops across New England.

Most people who owned it saw nothing unusual, just an old family portrait with that peculiar stiffness that characterized early photography.

In 2019, the portrait was purchased by digital archivist Rebecca Chen during a visit to a vintage shop in Providence, Rhode Island.

Rebecca specialized in restoring and preserving historical photographs using modern scanning technology and software.

She was drawn to the Harrison portrait because of its excellent condition and the clear quality of the original print.

She paid $35 for it, intending to use it as a practice piece for a new restoration technique she was developing.

Rebecca brought the portrait back to her studio in Boston, a converted loft space filled with scanning equipment, multiple computer monitors, and filing cabinets containing thousands of digitized historical images.

She carefully removed the photograph from its frame, noting the inscription on the back, Harrison family, October 1902, Asheford, Connecticut.

The scanning process began on a Tuesday afternoon.

Rebecca used a highresolution flatbed scanner capable of capturing details invisible to the naked eye in the original print.

As the scan progressed line by line, the image appeared on her monitor with stunning clarity.

The grain of the original photograph, the texture of the family’s clothing, the individual leaves on the trees in the background, everything emerged with remarkable definition.

Rebecca completed the initial scan and began the restoration process.

She worked methodically, removing scratches, adjusting contrast, and enhancing details that had faded over more than a century.

She started with the background, then moved to the parents, carefully bringing out the texture in James’ wool suit and the delicate lace on Elellanena’s collar.

If you’re enjoying this story so far, leave a like and subscribe to the channel.

It helps so much.

Then she reached the children.

As Rebecca zoomed in to work on their faces, applying careful adjustments to bring out detail in the shadows, she noticed something that made her pause.

Margaret’s eyes, which had appeared normal in the original print, now showed an unusual characteristic.

There was no light reflection in them, no catch light, no spark of life that typically appears when light hits the human eye during photography.

Rebecca assumed it was a scanning artifact and continued working.

But when she moved to Thomas, she found the same thing.

His eyes, like his sisters, were completely flat, absorbing light rather than reflecting it.

They appeared almost black despite the children having been described in family records as having light colored eyes.

Her hand trembled slightly as she zoomed in on Elizabeth’s face.

The youngest child stared out from the photograph with those same dark, empty eyes.

But there was something else.

Something Rebecca couldn’t initially quantify.

The expression wasn’t quite right.

It was too composed, too still, even for a Victorian era photograph where subjects were expected to remain motionless.

Rebecca sat back from her computer, her heart racing.

She had restored hundreds of historical photographs, including many from the same era.

She was familiar with the technical limitations of early photography, the long exposure times, the inconsistent lighting, the chemical variations in developing processes, but this was different.

She zoomed out, looking at the full portrait again.

James and Elellanena Harrison looked perfectly normal.

Their eyes showed the expected light reflections.

Their expressions, while formal, carried warmth and personality.

But their children looked fundamentally wrong in a way Rebecca couldn’t articulate.

She spent the rest of the evening researching technical explanations.

Could it be a problem with the original exposure? A developing error? Some quirk of the glass plate negative? She combed through photography forums, historical archives, and technical manuals from the period.

Nothing she found explained what she was seeing.

At midnight, Rebecca finally left her studio, but she couldn’t stop thinking about those eyes.

She returned the next morning and immediately pulled up the image again, hoping that fresh eyes might reveal a logical explanation.

But the children’s eyes remained as disturbing as they had been the night before.

dark, empty, and somehow aware.

Rebecca Chen couldn’t let the portrait go.

For 3 days, she barely left her studio, examining every pixel of the scanned image, searching for a rational explanation.

She consulted with colleagues, posting carefully cropped sections of the photograph to professional restoration forums without revealing the full context.

The responses varied, but none satisfied her growing unease.

Dr.

Marcus Thornton, a photography historian at MIT, with whom Rebecca had collaborated on previous projects, agreed to examine the image.

She sent him the highresolution scan via secure file transfer, and they scheduled a video call for that Friday afternoon.

Marcus appeared on screen in his cluttered office, surrounded by shelves packed with antique cameras and photographic equipment.

He was in his 60s with silver hair and wire rimmed glasses that he constantly adjusted while examining things closely.

Rebecca had always appreciated his methodical approach and his tendency to find logical explanations for unusual photographic phenomena.

I’ve looked at your Harrison portrait, Marcus began, his tone measured but tinged with something Rebecca couldn’t quite identify.

It’s remarkable and deeply troubling.

Rebecca leaned forward toward her camera.

So, you see it too, the eyes? I see several things, Marcus replied, pulling up the image on his own screen.

First, yes.

The children’s eyes show no light reflection whatsoever.

In photography of this period, that’s extraordinarily rare.

The long exposure times meant that even subtle movements could create blur, but light reflection in the eyes was almost always present.

Unless, he paused, and Rebecca prompted him.

Unless what? Unless the subject was deceased, Marcus finished quietly.

Postmortem photography was common in this era.

Families would pose with deceased loved ones, especially children, as a way of preserving their memory.

But in those photographs, the deceased were usually obvious.

They were lying down or their eyes were closed or they had a distinctly inanimate quality.

Rebecca felt a chill run down her spine.

But these children are sitting upright.

They’re posed naturally.

And look at their hands.

There’s no rigger mortise.

No discoloration.

Exactly.

Marcus agreed.

Which is why this is so confusing.

I’ve examined the image for signs of manipulation or double exposure.

Common tricks in that period.

I can’t find any.

This appears to be a single unmanipulated exposure.

The parents look alive.

The children look I don’t know what they look like.

They spent the next hour discussing technical possibilities.

Could the children have had some medical condition affecting their eyes? Unlikely, as three siblings would rarely share such a specific trait.

Could it be a chemical anomaly in the developing process? Possible, but it would be unprecedented for it to affect only the children’s eyes while leaving the rest of the image unaffected.

Marcus promised to do more research and suggested Rebecca try to trace the photograph’s provenence.

If you can find out more about this family, about what happened to them, it might explain what we’re seeing.

Sometimes the story behind the image illuminates the image itself.

Rebecca began her historical research that evening.

She started with census records, death certificates, and local newspaper archives from Asheford, Connecticut.

The Ashford Historical Society had a small but well-maintained digital archive, and she submitted several inquiries through their website.

Within 2 days, she received a response from Helen Mohouse, the historical society’s volunteer archavist.

Helen was a retired librarian in her 70s who had lived in Asheford her entire life.

Her email was brief, but intriguing.

I know the Harrison family.

There’s a story there.

Would you be willing to visit in person? Some things are better discussed face to face.

Rebecca drove to Ashford the following Saturday.

The town had changed significantly since 1902, but traces of its Victorian past remained visible in the architecture along Main Street.

The historical society occupied a renovated colonial building near the town center.

its rooms filled with display cases containing artifacts from Asheford’s past.

Helen Mohouse met Rebecca in the research room, a quiet space lined with filing cabinets and shelves of bound documents.

She was a small woman with sharp intelligent eyes and silver hair pulled back in a neat bun.

She carried a manila folder which she set on the table between them.

The Harrison family, Helen began, settling into her chair.

I’ve been volunteering here for 23 years, and their story is one of the strangest in Asheford’s history.

When you contacted us about the photograph, I knew immediately which one you meant.

We’ve had three other inquiries about it over the years, though we don’t actually have a copy in our collection.

She opened the folder, revealing several photocopied documents, newspaper clippings, handwritten letters, and what appeared to be pages from Oldtown records.

James and Elellanena Harrison moved to Ashford in 1895.

Helen continued, “James established a pharmacy on Main Street, which was quite successful.

Elellanena taught at the elementary school.

By all accounts, they were a respectable, well-liked family.

They had three children, Margaret, Thomas, and Elizabeth.

Rebecca listened intently as Helen laid out a timeline using the documents.

Everything matched the basic information she had already discovered.

But then Helen reached a newspaper clipping from October 1902, and her expression darkened.

“This is where the story becomes difficult,” Helen said, sliding the clipping across the table.

The headline read, “Tragedy strikes Harrison family.

Three children lost in fire.

” Rebecca’s hands trembled as she picked up the clipping.

The article dated October 11th, 1902, described a devastating houseire that had occurred in the early hours of October 10th.

The children, Margaret, Thomas, and Elizabeth, had all perished.

James, and Elellanena, had been visiting Elellanena’s sister in Hartford at the time.

The children had been left in the care of a housekeeper, Mrs.

Dawson, who had also died in the blaze.

The fire started around 2:00 in the morning, Helen explained.

The cause was never definitively determined, though investigators suspected a fallen oil lamp.

By the time neighbors noticed the flames, the house was fully engulfed.

The children never made it out.

Rebecca stared at the article, her mind racing.

But the photograph, it’s dated October 1902.

When exactly was it taken? Helen pulled out another document, a handwritten receipt from Samuel Witmore’s photography studio.

October 5th, 1902, 5 days before the fire.

Leave a comment below about what you think about this story so far.

The room seemed to grow colder.

Rebecca looked at the receipt, then back at the newspaper clipping.

So, the photograph was taken just days before they died.

That’s tragic, but it doesn’t explain what I’m seeing in the image.

Um, there’s more, Ellen said quietly.

She pulled out a letter yellowed with age and written in flowing Victorian script.

This is from Elellanena Harrison to her sister, dated October 12th, 1902, 2 days after the fire.

It was found in the historical society’s archives during a catalog project in the 1980s.

Someone donated a collection of family letters, and this was among them.

Rebecca took the letter carefully, aware she was holding a piece of genuine historical correspondence.

The writing was shaky, clearly written by someone in the grip of overwhelming grief.

Most of the letter contained the expected expressions of loss and despair, but one paragraph stood out.

The portrait arrived this morning, a cruel mockery of God.

Samuel Witmore delivered it himself, unaware of our tragedy.

When I unwrapped it, I nearly collapsed.

My darling children stare out from the frame.

But Mary, it is not truly them.

Something is wrong with their eyes.

They look at me, but they do not see me.

James insists it is merely my grief playing tricks, but I cannot bear to look at it.

I have asked him to remove it from my sight.

Rebecca read the passage three times, her pulse quickening.

Elellanena Harrison had noticed something wrong with her children’s eyes immediately upon receiving the portrait, before Rebecca’s digital restoration, before modern scanning technology revealed the details.

Did Ellena say anything else about the photograph? Rebecca asked.

Helen shook her head.

Not in any documents we have.

She and James left Asheford shortly after the funeral.

They moved to California trying to escape the memories.

James died in 1908.

Eleanor in 1954.

Neither ever returned to Connecticut.

What about the photographer Samuel Witmore? I looked into him as well, Helen replied.

He was a traveling portraitist who worked throughout New England from 1895 to 1903.

His work was considered quite good.

He had a reputation for capturing subjects with unusual clarity and detail.

But after 1903, he simply disappears from the historical record.

No death certificate, no further business records, nothing.

It’s as if he stopped existing.

Rebecca spent the next two hours examining every document in Helen’s folder.

There were details about the funeral, witness accounts of the fire, and information about the house itself.

Nothing provided any additional insight into the photograph’s disturbing qualities.

As Rebecca prepared to leave, Helen walked her to the door.

The older woman hesitated, then spoke.

There’s something else you should know.

It’s not documented, just local stories passed down through families.

But several people who lived on Maple Street in the years following the fire reported strange occurrences in the house before it was torn down in 1935.

What kind of occurrences? Lights in windows when the house was supposed to be empty.

Sounds of children playing.

And one family who briefly rented the house in 1910 moved out after only 3 weeks.

The mother claimed she kept seeing three children standing in the upstairs windows watching her.

Always three children, always perfectly still, always with those blank staring eyes.

Rebecca drove back to Boston in silence.

The documents Helen had copied for her resting on the passenger seat.

The rational part of her mind insisted there had to be a logical explanation, but every piece of evidence seemed to deepen the mystery rather than solve it.

That night she returned to her studio and pulled up the Harrison portrait once more.

She zoomed in on each child’s face, studying them with fresh eyes.

Margaret, the eldest, sat with her hands folded primly in her lap, her expression neutral.

Thomas, the middle child, had his shoulders squared, trying to look grown up for the camera, and Elizabeth, the youngest, stared directly at the lens with that unsettling composure.

Rebecca began examining other aspects of the photograph she hadn’t focused on before.

She noticed that while the parents cast clear shadows on the wall behind them, the children’s shadows were oddly faint, almost imperceptible.

She zoomed in on their hands.

They showed no signs of movement blur.

Despite the 8-second exposure time that would have revealed even the slightest fidget.

Then she noticed something else.

In the background, barely visible through one of the houses’s windows, there appeared to be a fourth figure.

She enhanced that section of the image, adjusting brightness and contrast until the figure became clearer.

It was a woman, elderly, standing perfectly still inside the house.

Her face was indistinct, but she appeared to be watching the family portrait session through the window.

Rebecca checked the historical records again.

Mrs.

Odorson, the housekeeper who died in the fire, would have been the only other person in the house that day.

Rebecca saved her work and sent an updated scan to Marcus along with a summary of what she had learned in Asheford.

His response came quickly.

This changes everything.

We need to talk.

The video call with Marcus Thornton took place at 1000 p.

m.

on Tuesday.

Both of them working late in their respective offices.

Marcus looked haggarded.

His usual professional composure replaced by visible unease.

I’ve spent the last 3 days researching Samuel Witmore, Marcus began without preamble.

What I found is troubling.

Rebecca, this wasn’t the only photograph of his with unusual properties.

He shared his screen displaying a gallery of portraits.

Each showed families or groups from the early 1900s, all bearing Samuel Witmore’s distinctive signature in the corner.

And in each photograph, Rebecca noticed similar anomalies.

Subjects whose eyes appeared flat and lifeless.

Shadows that didn’t quite match the lighting.

Subtle wrongness that was difficult to articulate but impossible to ignore.

I found these in various archives and private collections, Marcus explained.

Nine photographs total, all taken by Whitmore between 1900 and 1903.

And here’s the disturbing pattern.

In every single case, at least one person in the photograph died within 2 weeks of the picture being taken.

Rebecca felt her stomach tighten.

That could be coincidence.

Mortality rates were higher then, especially for children.

That’s what I thought, Marcus agreed.

But look at the specifics.

The Harrison children died 5 days after their portrait.

In this image, he highlighted another photograph.

A man named Robert Chandler appears with his business partners.

He’s the one with the unusual eyes.

He died 6 days later in a carriage accident.

And in this one, a wedding portrait.

The bride shows those same flat eyes.

She died on her honeymoon 9 days after the photograph from an unexplained illness.

Marcus brought up more examples, each following the same pattern.

The subjects with the unusual eyes died soon after the photograph was taken, often in tragic or unexpected circumstances.

Those in the photographs whose eyes appeared normal typically survived for decades.

I don’t believe in curses or supernatural causes, Marcus said firmly.

But I can’t explain this statistically.

The probability of this being random chance is astronomical.

What happened to Witmore? Rebecca asked.

You said he disappeared after 1903.

He did.

His last known photograph was taken in March 1903 in Burlington, Vermont.

After that, nothing.

I found one newspaper mentioned from May 1903.

A small article about an abandoned photography studio in Hartford.

The landlord told the reporter that Samuel Whitmore had failed to pay rent for 2 months and had left all his equipment behind.

Marcus paused, then continued.

I hired a genealogologist to search for death records, immigration records, anything.

There’s no trace of Samuel Whitmore after March 1903.

No death certificate, no burial record, no mention in any subsequent census.

For a man who left behind dozens of documented photographs and business records to simply vanish is nearly impossible.

If you’re still enjoying this video, leave a like and subscribe to the channel.

Your support means everything.

Rebecca leaned back in her chair, processing this information.

Could he have changed his name? Gone to another country? Possible, but unlikely given the circumstances.

The equipment he left behind was valuable.

Cameras, developing chemicals, glass plates.

Why would a professional photographer abandon his livelihood? They discussed theories for another hour, each more unsettling than the last.

Marcus had even contacted a psychologist who specialized in historical death photography, trying to find cultural or psychological explanations for the phenomenon.

Nothing fit cleanly.

There’s one more thing, Marcus said before they ended the call.

I found Whitmore’s journal.

Well, parts of it.

Three pages were preserved in an estate sale lot that ended up at the Vermont Historical Society.

There from October 1902, the same month he photographed the Harrison family.

He shared images of the journal pages.

The handwriting was precise but showed signs of agitation in certain passages, crossed out words, heavy pen strokes, and increasingly erratic margins.

Rebecca read aloud from the first page.

October 3rd, 1902.

The Harrison family sitting scheduled for October 5th.

I dreamed of them last night, though I have never met them.

Three children with empty eyes standing in flames.

I woke unable to breathe.

Catherine insists it is merely anxiety, but I cannot shake the feeling of dread.

The second page was dated October 7th, 2 days after the Harrison portrait was taken.

The session was wrong from the beginning.

The children were too still, too calm.

When I looked through the camera, I felt I was seeing something other than what was before me.

The eldest girl, Margaret, stared at the lens with such intensity that I nearly stopped the exposure.

But I completed the work.

Professional obligations.

Now I cannot sleep.

I see those children’s faces whenever I close my eyes.

The final page was barely legible.

The handwriting deteriorating into frantic scrolls.

October 13th, 1902.

The children are dead.

Fire took them.

But I knew, God help me.

I knew when I made their portrait.

The camera shows the truth.

It shows what is coming.

I should have warned them.

Should have refused.

The others didn’t listen.

I tried to tell Mrs.

Chandler.

tried to explain about her husband’s portrait, but she thought me mad.

How many more? How many more will I photograph only to watch them die? I cannot do this anymore.

I cannot.

Rebecca stared at the screen long after Marcus had stopped sharing.

He knew, she whispered somehow.

He knew the children were going to die.

Or he believed he knew, Marcus corrected.

We can’t determine his actual state of mind from these entries.

he may have been experiencing some form of psychological breakdown.

The stress of his profession combined with a series of tragic coincidences could have convinced him that his photographs were somehow predicting or causing deaths.

But the photographs themselves, Rebecca insisted, the eyes, the shadows, these are real, observable anomalies.

Yes, Marcus agreed reluctantly.

Those are real.

What they mean, I can’t say.

After the call ended, Rebecca sat alone in her studio, the Harrison portrait displayed on her monitor.

She found herself unable to look away from those three children, forever frozen in that October morning in 1902.

What had they seen? What had Whitmore seen through his camera lens? She decided to dig deeper into the day of the fire itself.

Helen Mohouse had provided newspaper accounts, but Rebecca wanted more detail.

She contacted the Connecticut State Library, which maintained extensive historical archives and requested any available documentation related to the Harrison house fire.

2 days later, she received a package containing photo copies of the official fire investigation report, witness statements, and coroner’s records.

She spread the documents across her desk and began reading systematically.

The fire had started around 2:15 a.

m.

on October 10th.

The first witness to notice was a neighbor named Thomas Garrett, who lived two houses down from the Harrisons.

His statement provided chilling details.

I was awakened by a sound I can only describe as screaming, though not quite human.

I looked out my window and saw flames already consuming the upper floor of the Harrison house.

I ran downstairs and outside, shouting for help.

Several neighbors emerged and we attempted to approach the house, but the heat was too intense.

I heard no sounds from inside, no crying, no calls for help.

By the time the fire brigade arrived, the structure was collapsing.

They recovered four bodies the next morning, all burned beyond recognition.

They were identified by location and size.

Another neighbor, Mrs.

Katherine Wells, provided an even more disturbing account.

I was awake.

nursing my infant son.

When I happened to glance out the window, I saw the Harrison house before it was fully ablaze, perhaps 15 or 20 minutes before Mr.

Garrett raised the alarm.

I noticed lights in the children’s bedroom windows, which struck me as odd given the hour.

Then I saw three small figures standing in the windows, perfectly still.

I assumed the children had been awakened by something and were looking outside.

I nearly went to investigate, but my son needed me.

When I looked again, perhaps 5 minutes later, the flames had started.

I will never forgive myself for not going to check on those children immediately.

The coroner’s report was clinical and brief.

The four bodies, three children and one adult woman, had died from smoke inhalation before the flames had reached them.

The children had been found in their beds.

Mrs.

Dawson had been found in the hallway between the children’s rooms, apparently attempting to reach them.

But there was one detail that Rebecca found particularly disturbing.

The coroner noted that based on the progression of the fire and witness statements, the victims would have died approximately 20 to 30 minutes before the flames became visible from outside.

Yet Mrs.

Wells had seen figures in the windows during that window of time.

Rebecca cross-referenced the timing.

Mrs.

Wells had seen the children standing in the windows around 1:45 a.

m.

The coroner estimated death occurred between 1:50 and 2 S.

M.

The figures Mrs.

Wells had seen were either the children in their final moments before the smoke overwhelmed them.

Or Rebecca didn’t want to complete that thought.

She returned to the photograph, examining it with fresh eyes.

She zoomed in on the background again, enhancing the window where she had spotted the figure of Mrs.

Dawson.

The housekeeper stood perfectly still, just as the children did, just as Mrs.

Wells had described seeing through the windows on the night of the fire.

On impulse, Rebecca decided to examine the photograph using infrared analysis, a technique that could sometimes reveal details invisible in normal light.

She loaded the scan into specialized software and applied various filters.

When she applied the thermal signature filter, a tool that could detect variations in heat patterns captured in certain types of old photographs, the results made her blood run cold.

The three children showed no heat signature at all.

Their bodies registered as cold spots in the thermal map, while their parents and the background elements showed normal variations.

It was as if the children in the photograph had no warmth, no life, despite appearing fully present in the visible spectrum.

Rebecca stumbled back from her computer, her heart racing.

This was impossible.

Photography in 1902 couldn’t capture thermal signatures in any meaningful way.

Yet the data was there, clear and undeniable.

She forced herself to think rationally.

Could this be a quirk of the digitization process, some artifact of her restoration work? She ran the original scan through the same analysis without any of her enhancements.

The result was identical.

At midnight, Rebecca received an email from Marcus.

The subject line read, “You need to see this immediately.

” She opened it to find a message and an attachment.

Rebecca, I was contacted today by a woman named Dr.

Evelyn Cross from Boston University’s psychology department.

She’s been researching historical cases of death premonition photography, a phenomenon that was actually documented and studied in the early 1900s.

I’m forwarding her paper.

Call me when you’ve read it.

Rebecca downloaded the attachment, a 47page academic paper titled Precognitive Photography, an analysis of death premonition cases from 1890 1910.

She made coffee and began reading.

Doctor Cross’s paper was meticulously researched, documenting dozens of cases where photographs seem to predict or foreshadow the subject’s death.

Most of the cases were explained as coincidence or confirmation bias.

People remembering unusual photographs only after a tragedy occurred, but there was a category of cases that resisted conventional explanation.

Samuel Witmore was mentioned specifically in the paper.

Doctor Cross had identified 15 of his photographs that showed the unusual eye phenomenon, all connected to subsequent deaths.

She had even tracked down descendants of some of the subjects and interviewed them.

Several reported that their ancestors had felt inexplicably disturbed by their portraits and had hidden or destroyed them.

The paper’s conclusion was cautiously worded but striking.

While no mechanism for genuine precognitive photography has been scientifically established, the cluster of cases associated with Samuel Witmore’s work between 1900 and 1903 presents statistical anomalies that deserve further investigation.

The consistency of the reported phenomena, unusual eye appearance, feelings of dread, subsequent deaths within a narrow time frame, suggests either an undiscovered photographic process, or a shared psychological phenomenon worthy of serious study.

Rebecca finished reading at 3:00 a.

m.

She called Marcus despite the late hour.

He answered on the first ring, clearly still awake.

“Did you finish the paper?” he asked.

“Yes, Marcus, what are we dealing with here?” There was a long pause.

“I don’t know, but I think we need to bring in Dr.

Cross.

She’s been studying this longer than either of us, and she might have insights we’re missing.

” They arranged a meeting with Evelyn Cross for the following week at Rebecca’s studio.

In the meantime, Rebecca continued her analysis of the Harrison portrait, documenting every anomaly, every unusual detail.

She created a comprehensive report with highresolution images, technical measurements, and historical context.

But she found herself increasingly reluctant to spend time alone with the photograph.

There was something about those children’s eyes that seemed to follow her around the room.

Several times she could have sworn she saw movement in the image when she wasn’t looking directly at it.

A subtle shift in the children’s expressions, a change in the depth of those dark eyes.

She told herself it was exhaustion, stress, the power of suggestion.

But each night she had nightmares of standing in a burning house, watching three children with empty eyes staring at her from upstairs windows, perfectly still as flames consumed everything around them.

Dr.

Evelyn Cross arrived at Rebecca’s studio on a gray Tuesday morning in early November.

She was younger than Rebecca had expected, mid30s, with dark hair pulled back in a practical ponytail and an intensity in her eyes that suggested someone who had spent too many late nights pursuing uncomfortable truths.

Marcus Thornton joined them via video call, his image displayed on one of Rebecca’s monitors.

The three of them stood around the large table where Rebecca had laid out printouts of the Harrison portrait along with all her research materials, thermal analyses, and historical documents.

I’ve been studying this phenomenon for 6 years, Evelyn began, examining the portrait with careful attention.

Samuel Witmore is central to my research, but I’ve never seen this particular photograph in such high resolution.

The detail you’ve captured through restoration is remarkable and deeply unsettling.

She pulled a laptop from her bag and opened a folder containing her own collection of Witmore’s photographs.

Side by side, the similarities were undeniable.

Each photograph that preceded a death showed the same characteristics.

flat, lifeless eyes, unusual shadow patterns, a subtle wrongness that was difficult to articulate but impossible to ignore once noticed.

“I need to share something that didn’t make it into my published paper,” Evelyn said, her voice dropping.

“I’ve interviewed 12 people who owned or inherited Whitmore’s photographs.

Seven of them reported persistent nightmares after the photographs came into their possession.

Four experienced what they described as premonitions or visions, two became convinced the photographs were watching them.

Of those 12 people, nine eventually destroyed or gave away the photographs.

They couldn’t bear to keep them, Rebecca felt a chill.

I’ve been having nightmares, she admitted, since I started the restoration.

Three children in burning windows, always perfectly still, always staring.

Evelyn nodded as if she’d expected this.

That’s consistent with other reports.

It’s as if the photographs carry some kind of psychological weight, some emotional residue from the original subjects or circumstances.

But that’s not scientifically possible, Marcus interjected from the screen.

Photographs are just chemical reactions on paper, or in this case, pixels on a screen.

They can’t carry emotional content or cause specific psychological effects, can’t they? Evelyn challenged.

Consider the power of images.

We know that certain photographs can trigger strong emotional responses, pictures of loved ones, images of trauma.

The mind is capable of imbuing photographs with tremendous meaning.

Perhaps in cases where the photograph was taken just before a tragedy, that proximity to death somehow imprints itself.

She pulled out a Manila folder containing more documents.

I want to show you something I discovered about the day the Harrison portrait was taken.

I obtained the original weather records for Ashford, Connecticut, October 5th, 1902.

She spread out the photocopied meteorological data.

According to the official records, October 5th, 1902 was a clear, sunny day with temperatures in the low60s.

Perfect conditions for outdoor photography.

But look at this.

She produced a newspaper clipping from the Ashford Courier dated October 6th, 1902.

Residents reported an unusual atmospheric phenomenon yesterday afternoon.

Several citizens described a sudden darkening of the sky around 300 p.

m.

accompanied by a drop in temperature and an oppressive feeling described as heavy or portentous and the disturbance lasted approximately 10 minutes before conditions returned to normal.

The weather service has no explanation for the occurrence.

Rebecca checked the receipt from Whitmore’s studio.

The portrait session was scheduled for 300 p.

m.

right when this phenomenon occurred.

Exactly, Evelyn said.

And there’s more.

I found Whitmore’s notes, not his journal entries, but his technical photography notes.

He was meticulous about recording exposure times, lighting conditions, chemical mixtures for developing.

For the Harrison portrait, he wrote this.

She showed them a photograph of a handwritten note.

Harrison family sitting.

October 5th, 1902.

3:17 p.

m.

Exposure.

Standard plate standard chemistry.

Anomalous atmospheric conditions during exposure.

Subjects appeared to flicker in viewfinder.

Exposure repeated three times due to technical concerns.

Third plate successful, but displayed unusual tonal qualities in development.

Unable to explain variation.

He took three exposures.

Rebecca asked, “What happened to the other two plates?” “I don’t know,” Evelyn admitted.

“There’s no record of them, but the fact that he tried multiple times suggests something was wrong from the beginning, something he could see through his camera.

” Marcus cleared his throat from the screen.

I need to play devil’s advocate here.

We’re building a narrative around coincidences and vague historical accounts.

Yes, the photograph has unusual properties.

Yes, the timing is unsettling, but we’re talking about people who died in a tragic fire days after having their picture taken.

That’s terrible, but it’s not supernatural.

You’re right, Evelyn agreed.

Which is why I want to focus on what we can measure and document.

Rebecca, can you show us the thermal analysis again? Rebecca brought up the thermal images on her monitor.

The three children appeared as cold spots devoid of heat signature while everything else in the photograph showed normal thermal variation.

“This is the evidence I find most compelling,” Evelyn said, “because it’s quantifiable.

It’s not about feelings or interpretations.

It’s measurable data that shouldn’t exist in a photograph from 1902.

The technology to capture thermal information didn’t exist then.

Yet, here it is.

” They spent the next 3 hours analyzing every aspect of the photograph using various technical methods.

Evelyn brought equipment Rebecca had never seen before.

Spectral analyzers, electromagnetic field detectors, even a device that measured what she called photonic density.

Every test produced anomalous results for the three children.

Their images showed lower spectral reflectance, minimal electromagnetic signature, and a photonic density that Evelyn described as consistent with absence rather than presence.

It’s as if they’re not fully there, Evelyn explained.

Not fully captured by the photographic process.

I’ve seen similar patterns in other Witmore photographs, but never this pronounced.

As afternoon wore into evening, their analysis was interrupted by a phone call to Evelyn’s cell.

She stepped away to answer it, and Rebecca could hear her speaking in low, urgent tones.

When she returned, her expression was troubled.

That was a colleague from the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Evelyn said, “There’s been a development.

A man named Robert Witmore contacted them this morning.

He claims to be Samuel Witmore’s greatgrandson.

He says he has materials related to his greatgrandfather that he’s willing to share, but only under specific conditions.

D.

What conditions? Marcus asked.

He’ll only meet in person, and he insists on meeting somewhere public and neutral.

He’s apparently been trying to learn about his great-grandfather’s work for years, but family members have been reluctant to discuss it.

He found my research paper and tracked me down through the historical society.

They arranged to meet Robert Whitmore two days later at a cafe in Cambridge.

Rebecca spent the intervening time continuing her analysis of the Harrison portrait, but she found her attention repeatedly drawn to one detail she hadn’t fully explored, the figure in the window behind the family.

She enhanced that section of the image as much as possible, using every technique at her disposal.

The figure almost certainly Mrs.

Dawson, the housekeeper, stood motionless inside the house, visible through the window.

Rebecca zoomed in on the woman’s face.

Her eyes were the same as the children’s, flat, dark, lifeless.

Rebecca checked the historical records again.

Mrs.

Dawson had died in the fire along with the children.

Had Samuel Whitmore somehow seen her death coming as well? had his camera captured something invisible to the naked eye, a presentiment of mortality, a shadow of what was to come.

She shared this discovery with Evelyn and Marcus.

Neither had a satisfactory explanation.

On Thursday afternoon, they met Robert Witmore at a quiet cafe near Harvard Square.

He was in his late 50s, tall and thin with graying hair and an anxious demeanor.

He carried a leather portfolio which he held close to his body as if afraid someone might snatch it away.

After introductions, Robert began speaking in a quiet, rushed voice.

I didn’t know much about my greatgrandfather until I started researching my family history 5 years ago.

My grandmother, Samuel’s daughter, never spoke about him.

When I asked why, she would only say that he had been troubled and that his work had caused him great pain.

She died in 1998, taking most of her secrets with her.

He opened the portfolio, revealing a collection of documents and photographs.

I found these in her attic after she passed.

She had kept them hidden, wrapped in cloth, and locked in a trunk.

I think she couldn’t bring herself to destroy them, but she didn’t want anyone to find them either.

The first item was a photograph of Samuel Witmore himself, a formal portrait from around 1900.

He appeared to be in his 30s with intense eyes and a serious expression.

But what drew Rebecca’s attention was the background.

In the shadows behind Whitmore, barely visible, there were faces, indistinct, blurred, but unmistakably present.

Dozens of faces, maybe more, staring out from the darkness.

That’s his self-portrait, Robert explained.

He took it in 1901.

I had it analyzed by a photographic expert who confirmed it’s a single exposure, not a multiple exposure or manipulation.

Those faces in the background, they shouldn’t be there.

The photograph was taken in an empty studio.

Evelyn examined the portrait closely.

Does your family history explain what was happening to him? Why his photographs developed these properties? Robert pulled out a letter, yellowed and fragile.

This is from Samuel to his wife, Catherine, written in February 1903.

It’s the last communication anyone in the family received from him.

He handed the letter to Evelyn, who read it aloud.

My dearest Catherine, I can no longer continue this work.

The camera shows too much.

Not just what is, but what will be.

When I look through the viewfinder, I see beyond the moment into something deeper and darker.

I see death approaching those who stand before my lens.

I see the shadows that follow them, the emptiness that will soon consume them.

The children haunt me most.

I have photographed so many children, and in too many cases I have seen that terrible stillness in their eyes through my camera, a stillness that tells me they have little time remaining in this world.

I tried to warn their families.

I tried to refuse commissions when I sensed what was coming, but they thought me mad or cruel or both.

I cannot be the harbinger of death any longer.

I cannot keep documenting the moments before tragedy.

The camera has become a curse, showing me truths I never wished to see.

Last night, I dreamed I was developing photographs in my dark room.

But instead of images appearing on the plates, I saw faces of the dead rising from the chemical baths, accusing me, asking why I did not save them.

I’m leaving the profession.

I’m leaving everything.

Perhaps in time I can forget what I have seen, what the camera has shown me.

Forgive me for abandoning you, but I cannot remain the man who photographs souls on the edge of departure.

your loving husband, Samuel.

The cafe had gone quiet around them.

Finally, Marcus spoke from Rebecca’s phone, which she’d propped up on the table.

Did he ever contact the family again? Robert shook his head.

Never.

My grandmother tried to find him for years.

She hired private investigators, placed advertisements in newspapers across the country.

Nothing.

It was as if he’d simply ceased to exist.

She eventually remarried and took her second husband’s name.

She rarely spoke of her father, and when she did, it was with a mixture of sadness and fear.

“Fear?” Rebecca asked, “She believed he was right,” Robert said quietly about the camera showing too much.

She told me once when I was a teenager that her father had seen something in the world that human beings weren’t meant to see.

A truth about mortality and time that drove him away from everyone he loved.

He pulled out the final item from his portfolio, a small leatherbound journal.

This is Samuel’s dark room log from 1902.

every photograph he developed, every technical note, every observation.

I think you’ll find the entries for October particularly relevant to your research.

Rebecca took the journal carefully, aware she was holding a piece of genuine historical evidence that could reshape their entire understanding of the case.

She opened it to October 1902 and began reading.

Samuel Witmore’s final entries painted a picture of a man descending into obsessive awareness of mortality.

He documented seeing the shadow of death in the eyes of multiple subjects.

He described feeling ill after certain photography sessions, experiencing nightmares, and being unable to eat or sleep properly.

But one entry from October 8th, 1902, 3 days after photographing the Harrison family and 2 days before the fire, was particularly chilling.

I can no longer close my eyes without seeing the Harrison children.

Their faces appear before me in the darkness, asking why I did not warn them, why I took their portrait, knowing what I saw through my lens.

But I did not know for certain.

I never know for certain.

I see only shadows, implications, a quality of light that suggests absence rather than presence.

How can I tell a mother that her children’s souls appear dim to my camera? How can I explain that when I look at their image, I feel cold despite the summer heat? The girl, Margaret, stared at me during the session, not at the camera, at me through the lens, as if she could see me seeing her, as if she knew what I was documenting.

I’ve developed the plate three times, hoping I was mistaken, hoping the chemicals would reveal something different.

But each time those eyes stare back at me, empty of light, empty of future.

If something happens to those children, their blood will be on my hands.

Not because I caused it, but because I saw it coming and said nothing.

2 days later, the children were dead.

If you enjoyed this video, leave a comment below.

I’d love to know your thoughts and answer any questions.

Rebecca closed the journal, her hands trembling.

Around the table, no one spoke for a long moment.

Finally, Evelyn broke the silence.

Samuel Witmore wasn’t causing the deaths,” she said slowly.

“He was just seeing them before they happened.

his camera or his process or something about his particular sensitivity combined with the technology.

It allowed him to perceive something invisible to others, a temporal shadow, maybe an echo of the future bleeding backward into the present moment.

That’s impossible, Marcus said.

But his voice lacked conviction.

Is it? Evelyn challenged.

We already know that time isn’t as straightforward as we perceive it.

Physics tells us that past, present, and future exist simultaneously.

It’s only our consciousness that moves through them in one direction.

What if some people under certain circumstances with certain tools can perceive beyond the immediate present? What if Samuel Witmore was one of those people and his camera was the tool that made it visible? Robert Whitmore had been listening quietly.

Now he spoke.

There’s one more thing.

My grandmother told me something else before she died.

She said that in the last letter she received from my great-grandfather, he wrote, “The camera doesn’t lie, but it shows truths we are not meant to see.

I have looked too long at what lies beyond the edge of life, and now I cannot look away.

I’m going to a place where cameras don’t exist, where images can’t be captured, where the future remains mercifully hidden.

” She always believed he’d gone somewhere remote, Alaska maybe, or deep into the western territories to live out his days without the burden of seeing death approach.

Rebecca thought about the Harrison portrait still displayed on her studio monitor.

Those three children forever frozen in the moment 5 days before their deaths, staring out with eyes that somehow already knew what was coming.

“What do we do with this information?” she asked.

How do we explain it? We can’t, Evelyn said flatly.

Not in any way that would be accepted by academic or scientific communities.

We can document the anomalies, present the evidence, but the conclusion that Samuel Whitmore’s photographs somehow captured precognitive information about his subjects is too far outside conventional frameworks.

We’d be dismissed as cranks or conspiracy theorists.

Marcus sighed from the phone screen.

She’s right.

We can publish the technical analysis, the historical research, the statistical anomalies, but we can’t state the obvious conclusion without destroying our professional credibility.

So the truth just remains hidden, Rebecca asked.

All these photographs, all these people who died, all this evidence, it just gets filed away as an unsolved curiosity.

Some truths are too uncomfortable, Robert Whitmore said quietly.

My grandmother understood that.

It’s why she hid these materials rather than destroying them.

She wanted the evidence to exist, but she didn’t want to force anyone to confront what it meant.

Some mysteries are better left mysterious.

They talked for another hour, discussing possibilities and implications, but ultimately reached no satisfying conclusion.

Robert agreed to let Rebecca and Evelyn make copies of the materials he’d brought, but he asked them to be judicious about what they published.

“My greatgrandfather was driven into exile by what he saw,” Robert said as they prepared to part ways.

I

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load