In the summer of 1857, three widows in Charleston, South Carolina did something that would scandalize their entire community.

They pulled their money together and purchased a young man at auction.

What happened behind the closed doors of their shared estate would lead to two dead bodies, a townwide investigation, and a secret so disturbing that even the judge presiding over the case ordered all records sealed for 50 years.

The Charleston Slave Market on Meeting Street operated like clockwork every Tuesday and Friday.

Buyers arrived early, inspecting merchandise with a clinical detachment of farmers purchasing livestock.

But on July 14th, 1857, something unusual caught the attention of the regular traders.

Three women entered together, all dressed in black morning clothes despite their husbands having died years apart.

Catherine Whitmore, 42, had buried her tobacco merchant husband 3 years prior.

Eleanor Ashford, 38, lost her shipyard owner husband to yellow fever in 1854.

Margaret Cordell, the youngest at 34, became a widow when her cotton plantation owner husband died in a riding accident just 18 months earlier.

None of them needed to be there.

Each woman had inherited substantial estates.

Each employed multiple household slaves.

Each had the means to purchase labor independently.

Yet they arrived together, sat together, and bid together.

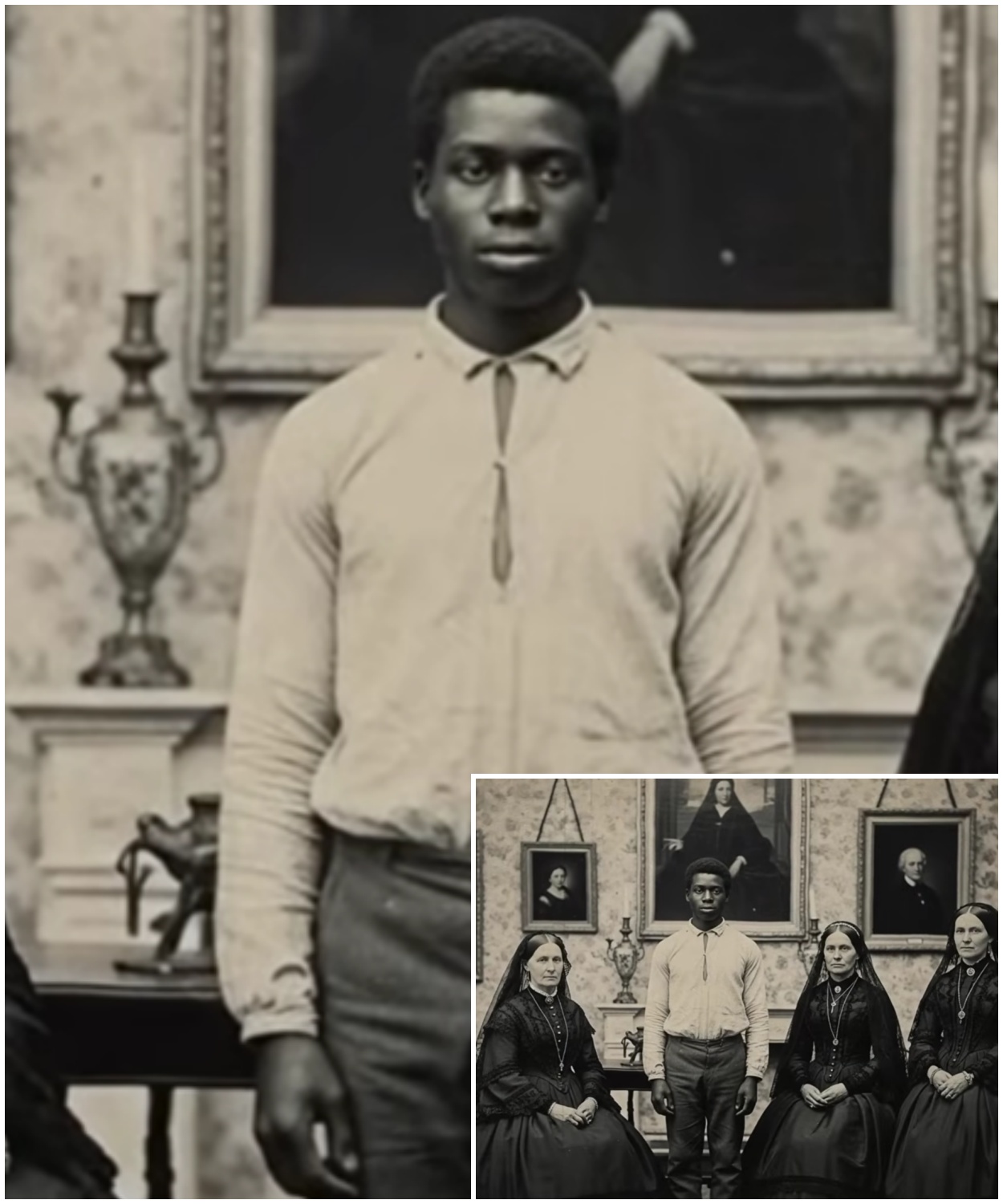

The auctioneer brought forth Lot 47, an 18-year-old fieldand named Samuel, recently transported from a failing plantation in Virginia.

He stood 6 ft tall, unusually educated for his circumstance, able to read and write, which his previous owner had foolishly permitted before financial ruin forced the sale of his property.

The bidding started at $300.

Within minutes, it escalated beyond reason.

Plantation owners who needed strong backs for their fields dropped out at 600.

The three widows continued, their unified bids spoken in turns like a rehearsed performance.

At $1,50, the hammer fell.

The price was absurd for a single field hand.

Several buyers exchanged knowing glances.

In the economy of human flesh, something didn’t add up.

The women paid in cash, collected their receipt, and departed with Samuel walking 10 paces behind them.

They didn’t take him to any of their individual estates.

Instead, they directed him to a property none of them officially owned, a secluded three-story townhouse on the edge of the historic district, purchased under a business arrangement 6 months earlier.

The neighbors knew little about this house except that it remained perpetually shuttered and that deliveries arrived after dark.

As Samuel crossed the threshold that afternoon, the door closed behind him.

He wouldn’t be seen in public again for 11 months.

And when he finally emerged, two of the women who purchased him would already be dead.

The house on Longitude Lane operated under rules that defied the conventional master slave dynamic of Antabbellum Charleston.

Samuel wasn’t assigned to fieldwork, kitchen duty, or any labor that defined plantation slavery.

Instead, he was given a room on the second floor, furnished better than most free workers could afford.

Catherine Whitmore explained the arrangement the first evening.

The three widows had formed what they called a domestic cooperative after discovering their shared circumstances through Charleston’s tight-knit society of bereieved wives.

Each had wealth, but no male heir, no son to manage estates, no husband to provide the social legitimacy that southern society demanded.

They needed something specific from Samuel, and they were willing to pay extraordinarily well for it.

His duties were unconventional.

He would serve as their shared companion, confidant, and public escort when necessary.

In private, he would provide intellectual conversation, read aloud from books they couldn’t openly discuss in mixed company, and offer perspectives from a world their privileged positions had shielded them from experiencing.

On the surface, it appeared almost benign, an eccentric arrangement between wealthy women and an educated young man.

But Charleston society in 1857 didn’t permit such arrangements to exist without consequence.

The women rotated schedules.

Catherine claimed Monday and Thursday evenings.

Eleanor took Tuesday and Friday.

Margaret reserved Wednesday and Saturday.

Sundays Samuel had to himself, though he remained confined to the property.

During those first weeks, the arrangement maintained a facade of propriety.

Conversations remained intellectual.

Samuel read from Plutarch’s lives, discussed agricultural innovations, and answered questions about his upbringing on a Virginia plantation where his master had taught him letters as an experiment improving human educility.

But the boundaries began shifting in ways subtle and unmistakable.

Eleanor Ashford started requesting that Samuel dine with her rather than eating separately in the kitchen.

She asked increasingly personal questions about his thoughts on freedom, love, and what he imagined life could be beyond the institution that owned him.

Margaret Cordell commissioned a tailor to make Samuel proper evening clothes, stating that his appearance reflected on their collective reputation.

She began taking him on evening walks through the garden, conversing in ways that would have horrified her late husband’s family.

Catherine Whitmore, the eldest and most pragmatic of the three, watched these developments with growing concern.

She had initiated the cooperative with specific boundaries in mind, companionship without complication, intellectual engagement without emotional entanglement.

By September, those boundaries had dissolved entirely.

What started as an unusual business arrangement was transforming into something far more dangerous.

In 1857 Charleston, the consequences for crossing certain lines didn’t distinguish between willing participants and coerced ones.

The law recognized only one crime, and the penalty was death.

Keep watching to understand how quickly everything unraveled.

The first fight between the widows occurred on a Tuesday evening in late September.

Samuel was reading Dante’s Inferno aloud to Eleanor when Catherine arrived 2 hours early for her scheduled Thursday evening.

She found them seated closer than propriety allowed.

Eleanor’s hand resting on Samuel’s arm as he described the circles of hell.

The argument that followed shook the foundations of their cooperative.

Catherine accused Eleanor of violating their agreement.

Eleanor countered that no written document specified emotional boundaries.

Margaret, summoned to mediate, suggested they dissolve the arrangement entirely and grant Samuel his freedom.

That suggestion created an irreparable fracture.

Catherine refused, not out of cruelty, but calculation.

Freeing Samuel meant questions from magistrates, documentation that would expose their arrangement, scrutiny that could destroy their reputations and invalidate their control over their late husband’s estates.

They were trapped by the very system they had attempted to circumvent.

Samuel, present during this argument, understood something the women didn’t yet grasp.

He had become the most dangerous person in Charleston.

He knew too much, had witnessed too much, and represented evidence of transgressions that southern law punished with execution.

His education, once an asset, now became a liability.

He could document everything.

He could testify.

He could destroy all three women with a single conversation to the wrong magistrate.

That night, lying in his second floor room, Samuel recognized that his life expectancy had shortened considerably.

The women had created a situation with no lawful exit.

And in Charleston, such situations typically resolve themselves with a body and a convenient story.

He began planning his escape.

October brought a cold front unusual for South Carolina, temperatures dropping into the 40s at night.

Inside the house on Longitude Lane, the atmosphere turned colder still.

The cooperative had fractured into competing factions.

Eleanor and Margaret formed an alliance, proposing they relocate to Philadelphia, where they could manummit Samuel legally and continue their association without the suffocating restrictions of southern society.

Catherine rejected this plan outright, recognizing it as precisely the romantic delusion that would destroy them all.

Northern cities offered no sanctuary for interracial relationships in 1857.

The Fugitive Slave Act made harboring runaways a federal crime.

Even legally freed blacks faced constant scrutiny, violence, and the perpetual threat of being kidnapped and sold south again.

Catherine understood that relocating wouldn’t solve their problem.

It would merely change the jurisdiction where they’d be prosecuted.

She proposed an alternative.

Maintain the current arrangement indefinitely, enforce strict boundaries, and ensure Samuel remained profitable enough to justify the investment.

Treat him well, but remember what he was, property, not a partner.

This pragmatism drove Eleanor to fury.

During an argument on October 19th, she said something that would later be recorded in court testimony.

He’s more human than any of our dead husbands ever were.

Catherine’s response was immediate and calculated.

She began documenting everything in a leather journal.

Dates, times, conversations, boundary violations.

She was building a legal defense for whatever came next.

Meanwhile, Samuel navigated increasingly dangerous terrain.

Eleanor confessed feelings she shouldn’t have possessed.

Margaret asked questions about his desires for a future that couldn’t exist.

Catherine watched him with a cold assessment of someone calculating a problem’s most efficient solution.

He attempted his first escape on October 23rd.

The plan was simple.

During his Sunday solitude, he would exit through the garden door, make his way to the docks, and stow away on a vessel bound for anywhere.

He had memorized shipping schedules from newspapers the women left scattered around the house.

He made it as far as the garden gate before discovering it padlocked with a mechanism he couldn’t pick.

The three widows, despite their conflicts, had unified on one point.

Samuel couldn’t be permitted to leave.

Catherine found him there at dawn.

She didn’t rage or threaten.

Instead, she explained the mathematics of his situation with brutal clarity.

If he escaped and was caught, he’d be executed as a runaway and the women would face questioning about why a literate slave fled from apparently good treatment.

If he escaped successfully, the women would report him stolen, and bounty hunters would pursue him through every northern state.

If he remained, he lived comfortably, but trapped.

“You’re valuable,” Catherine said.

“That’s both your protection and your prison.

” Samuel returned to his room.

The door, he noticed for the first time, now locked from the outside.

The house on Longitude Lane had transformed from an unconventional arrangement into a pressure cooker of conflicting desires, legal impossibilities, and mounting paranoia.

What happened next would leave two people dead and force the third to make a choice that would haunt Charleston’s legal system for decades.

Stay with this story because the darkest chapter is still ahead.

By November, the household operated under an unspoken state of siege.

The women barely spoke to one another outside of logistics.

Samuel’s schedule became rigid.

Meals delivered to his room, reading sessions conducted in supervised silence, no more evening walks or casual conversations.

Eleanor began showing signs of psychological fracture.

She stopped eating regularly, spent hours in her room writing letters she never sent, and made repeated suggestions about poison as a solution to impossible situations.

Margaret interpreted this as suicidal ideiation.

Catherine understood it as something far more dangerous.

On November 8th, Eleanor didn’t arrive for her scheduled evening.

Margaret went to check on her at her estate and found her collapsed in her bedroom, barely conscious, a half empty bottle of Ldnum on the nightstand beside her.

The doctor called it an accidental overdose.

The timing was too convenient to be accidental.

Eleanor survived but emerged changed, quiet, withdrawn, and focused on Samuel with an intensity that alarmed even Margaret.

She began insisting that they had to free him properly or end this mercifully.

Catherine recognized the threat immediately.

Eleanor had become unpredictable, a liability who might confess everything to a magistrate, a priest, or anyone who would listen.

On November 14th, Catherine visited a pharmacist in a neighboring district and purchased arsenic, claiming she had a rat problem in her warehouse.

She did have a rat problem, but it wasn’t the four-legged kind.

Eleanor Ashford died on November 21st, 1857 at approximately 3:00 in the morning.

The doctor attributed her death to heart failure, a complication of her recent Ldam overdose.

He signed the death certificate without demanding an autopsy.

Wealthy white women in Charleston rarely received such indignities.

Her funeral drew a respectable crowd.

Catherine and Margaret sat in the front pew, veiled in black, accepting condolences from society members who knew Eleanor, only as a tragic widow who never recovered from her husband’s death.

No one mentioned the house on Longitude Lane.

No one asked about the unusual financial partnership documented in Eleanor’s estate papers.

And absolutely no one questioned why Samuel, a slave owned jointly by three women, wasn’t present at his mistress’s funeral.

Because by the time Eleanor was buried, Samuel had already connected the dots.

He had watched Eleanor’s decline.

He had noticed Catherine’s pharmacy visit, overheard through walls deliberately left thin enough to permit eavesdropping.

He had observed Margaret’s growing fear and withdrawal.

Eleanor hadn’t died of heartbreak or accidental overdose.

She’d been murdered and Catherine had gotten away with it.

The morning after the funeral, Catherine arrived at the house with new documents.

She explained to Samuel and Margaret that Eleanor’s third of ownership now transferred according to their original cooperative agreement.

The property would be managed jointly between the two surviving widows.

Margaret signed the papers with trembling hands.

She knew what she was signing.

Complicity and murder, continued imprisonment of Samuel, and her own potential death warrant if she became inconvenient.

That night, Margaret came to Samuel’s room.

For the first time since the locks were installed, she carried the key and opened his door of her own valition.

We have to run, she whispered.

Both of us tonight.

Samuel recognized the trap immediately.

If they ran together, they’d be caught within days.

An interracial couple traveling through South Carolina in 1857 would trigger immediate pursuit.

They’d be captured and the resulting trial would expose everything.

The cooperative, the relationship, the circumstances of Eleanor’s death.

Catherine was counting on exactly this reaction.

She had murdered Eleanor to consolidate power and eliminate a liability.

Now she was maneuvering to force Margaret into a mistake that would eliminate the second liability.

Samuel explained this to Margaret with a patient logic of someone who’d spent his entire life calculating survival odds in a system designed to kill him.

She’s already one, he said.

The moment you run, you prove you’re guilty of everything she’ll accuse you of.

Margaret collapsed into sobbing.

She confessed everything.

Her love for Samuel, her horror at Eleanor’s murder, her certainty that Catherine would kill her, too, and her complete inability to see any path forward.

Samuel held her while she cried, understanding that this moment of human connection would likely be his last.

Margaret was too fragile, too emotional, and too wealthy to survive what came next.

The next morning, Catherine arrived to find Margaret’s bedroom empty.

A note on the dresser explained that Margaret had decided to visit relatives in Savannah for an indefinite period.

She would communicate through her lawyer regarding future arrangements for the cooperative.

Catherine read the note, set it aside, and asked Samuel a direct question.

Did she run? She left.

Samuel answered carefully.

I don’t know where.

Catherine studied him for a long moment, then nodded.

I suppose it doesn’t matter.

She’ll be back once she realizes she has nowhere else to go.

But Margaret never came back.

Two widows had purchased a slave together.

Now, one was dead, one had disappeared, and the third stood alone in a house filled with evidence of crimes that southern law punished with execution.

What Catherine Witmore did next would determine whether she survived with her reputation intact or joined Eleanor in an early grave.

The story’s darkest turn is just ahead.

Catherine spent the next 3 days methodically searching Margaret’s rooms.

She found hidden letters describing the cooperative in damning detail, diary entries that read like evidence transcripts, and most dangerously a detailed account of Eleanor’s symptoms before her death that any competent doctor would recognize as arsenic poisoning.

Margaret had been documenting everything, building a case against Catherine while pretending to remain complicit.

Catherine burned the documents in the fireplace, watching years of evidence curl into ash.

Then she turned her attention to the remaining problem.

Samuel.

He knew everything.

He had witnessed Eleanor’s decline, understood the timing of Catherine’s pharmacy visit, and could testify to conversations that would establish motive and opportunity.

As long as he lived, Catherine remained vulnerable to exposure.

But killing a slave she owned outright would trigger the exact scrutiny she’d murdered to avoid.

Slaves were property and property destruction required explanation, documentation, and potentially investigation.

She needed Samuel to die in a way that appeared natural, accidental, or justified.

On November 28th, Catherine informed Samuel that his circumstances were changing.

She was consolidating her holdings, selling the house on Longitude Lane, and relocating him to her deceased husband’s tobacco plantation outside Charleston.

Samuel understood immediately.

Isolation, removal from any potential witnesses, and an environment where deadly accidents occurred regularly.

He had one week to solve an impossible problem.

Escape without triggering pursuit.

Survive without resources in a society that criminalized his existence and somehow ensure Catherine faced consequences for Eleanor’s murder.

The solution, when it came to him, was as brutal as it was necessary.

Margaret Cordell’s body was discovered on December 3rd, 1857, floating in the Ashley River, just south of Charleston.

The coroner determined she had been in the water approximately 5 days, suggesting she died around November 28th, the same day Catherine announced Samuel’s relocation.

The official cause of death was listed as drowning, likely suicide, given her documented melancholy following Eleanor’s death.

No investigation was opened.

tragic widow overwhelmed by grief takes her own life.

The story was common enough to avoid scrutiny.

But Samuel knew better because he had been there.

November 28th had unfolded exactly as Catherine planned.

She arrived at the house with three hired men to transport Samuel to the plantation.

What she didn’t plan for was Margaret appearing at the front door, disheveled and desperate, carrying a pistol she barely knew how to operate.

Margaret had been hiding in a boarding house under a false name, gathering courage to report everything to the authorities.

But courage failed her at the critical moment.

Instead of going to the magistrate, she returned to confront Catherine directly.

The confrontation happened in the first floor parlor with Samuel locked in his upstairs room.

But the walls were thin and voices carried.

Margaret accused Catherine of murdering Eleanor.

Catherine denied nothing, but explained calmly why it had been necessary.

Eleanor was going to confess everything to a priest, seeking absolution for sins she couldn’t live with.

That confession would have destroyed all three of them.

“I saved us,” Catherine said.

“You should be thanking me.

” Margaret’s response was to raise the pistol.

She demanded Catherine confess to the authorities, demanded Samuel be freed immediately, demanded impossible things that revealed her complete disconnection from reality.

Catherine talked her down with practice patients, convinced her to lower the weapon, suggested they discuss this rationally over tea.

The tea was poisoned.

Margaret managed three sips before recognizing the bitter taste she’d learned to identify from Eleanor’s final days.

She dropped the cup, staggered toward the door, and made it as far as the garden before collapsing.

Catherine followed her outside, watched her convulse, and waited for the arsenic to finish its work.

Then she dragged Margaret’s body to her carriage, drove to the Ashley River in darkness, and rolled her into the water.

Samuel watched all of this from his second floor window.

When Catherine returned to the house covered in mud and river water, she found Samuel sitting calmly in the parlor.

She had forgotten to lock his door after the hired men departed.

“You saw,” Catherine said.

“It wasn’t a question.

Everything,” Samuel confirmed.

They stared at each other across a room that had witnessed two murders and countless smaller deaths of conscience and humanity.

“Catherine calculated quickly.

Killing Samuel now would require explanation for the hired men who’d seen him alive hours earlier.

Letting him live meant perpetual vulnerability.

The mathematics of murder had become impossibly complex.

“What do you want?” she finally asked.

Samuel had spent the last week preparing for exactly this question.

His answer was precise, calculated, and utterly unexpected.

I want to testify.

A slave demanding to testify against his owner in 1857 South Carolina was legal impossibility.

Slaves couldn’t testify in court against white people under any circumstances.

But Samuel had spent his entire life navigating impossible systems, and he had discovered a loophole that even Catherine’s calculating mind hadn’t anticipated.

What happens next will determine who survives and who faces the hangman’s noose.

Catherine laughed at the suggestion.

Slaves can’t testify.

You know that.

Not in criminal court, Samuel agreed.

But in probate proceedings concerning Eleanor and Margaret’s estates, I can provide depositions.

The cooperative agreement made me jointly owned property.

That gives me standing to provide evidence about the circumstances surrounding my owner’s deaths.

Catherine’s expression shifted from amusement to calculation.

Samuel was right.

Probate courts operated under different rules than criminal courts.

Property disputes required documentation of circumstances affecting estate transfers.

If Samuel provided deposition testimony describing Eleanor’s symptoms, Catherine’s pharmacy visit, and Margaret’s confrontation, it wouldn’t directly accuse Catherine of murder, but it would establish a pattern that Eleanor and Margaret’s relatives could use to demand criminal investigation.

What do you want? Catherine asked again, this time without the pretense of superiority.

Freedom, Samuel said.

Legal manumission documented properly with enough money to establish myself in Philadelphia.

In exchange, my deposition will describe Eleanor’s accidental overdose, Margaret’s suicide motivated by grief, and my own testimony that you treated both women with exemplary care until their tragic natural deaths.

It was blackmail structured as a business transaction.

Catherine appreciated the elegance.

And if I refuse, then I provide accurate testimony, accept whatever consequences follow, and watch you hang.

Catherine considered this for a long moment.

Then she walked to her writing desk, pulled out fresh paper, and began drafting manumission documents.

The agreement took 3 days to finalize.

Catherine’s lawyer questioned the unusual circumstances, but Catherine explained it as charitable gesture honoring Eleanor and Margaret’s progressive views on gradual emancipation.

The lawyer drafted the papers, filed them properly, and by December 10th, Samuel was legally free.

Catherine handed him $200 in cash and a train ticket to Philadelphia.

If you ever return to Charleston, she said quietly, I’ll have you killed, free or not, Samuel believed her.

He took the money, the papers, and left South Carolina that same evening.

He never returned.

But the story didn’t end there.

Charleston society accepted the official narrative of two tragic widows who died within weeks of each other.

Victims of melancholy and the devastating grief that claimed so many berieved women in that era.

The cooperative was dissolved.

The house on Longitude Lane sold to a merchant family from Virginia and Catherine Whitmore returned to managing her late husband’s tobacco business.

For 6 months, she appeared to have succeeded completely.

But Eleanor’s brother, Thomas Ashford, was a lawyer in Richmond with both the resources and the suspicion to investigate his sister’s death.

He arrived in Charleston in June 1858, requesting access to Eleanor’s estate documents and medical records.

What he discovered troubled him immediately.

A cooperative business arrangement between three widows to jointly purchase and house a male slave documented expenses for the longitude lane property that seemed excessive for storing furniture and most damning.

A final letter Eleanor had written but never sent found among her papers.

The letter addressed to Thomas but never mailed described the cooperative in vague terms but expressed Eleanor’s fear that circumstances had evolved beyond proper boundaries and that she was terrified of consequences that seem increasingly inevitable.

Thomas brought these documents to Charleston’s magistrate, demanding investigation into potential foul play.

The magistrate initially dismissed his concerns, but Thomas persisted.

He hired a private investigator, a former Pinkerton agent named Marcus Webb, who specialized in cases involving suspicious deaths among wealthy families.

Webb began interviewing neighbors near the Longitude Lane property.

Most claimed to know nothing, but several remembered seeing a young black man visible occasionally in upper windows, which contradicted Catherine’s description of the property as mere storage.

Web tracked down the doctor who signed Eleanor’s death certificate.

Under pointed questioning, the doctor admitted he hadn’t actually examined Eleanor before her death.

He’d been summoned after the fact and signed the certificate based on Catherine’s description of symptoms.

The pattern Webb uncovered suggested something far darker than melancholy.

In August 1858, Webb located Margaret’s former house staff.

One maid testified that Margaret had seemed frightened in the weeks before her death, that she’d asked strange questions about poison symptoms, and that she’d burned several documents in her fireplace the day before she disappeared.

Webb presented his findings to Thomas Ashford, who brought them to Charleston’s district attorney.

The evidence was circumstantial, but compelling.

Two women dead within two weeks, both connected to an unusual business arrangement, both having expressed fear before their deaths.

The district attorney opened a formal investigation.

Catherine learned of the investigation on August 15th when a sheriff’s deputy arrived at her estate requesting an interview.

She granted the interview with perfect composure, explaining the cooperative as a reasonable business arrangement, Eleanor’s death as a tragic accident, and Margaret’s death as suicide motivated by unbearable grief.

And the slave you purchased together? the deputy asked.

Freed and relocated to Philadelphia, Catherine answered.

A charitable gesture honoring my deceased partner’s progressive sentiments.

The deputy wrote this down, thanked Catherine for her cooperation, and departed.

Catherine immediately began preparing for the battle she knew was coming.

The investigation Catherine thought she’d avoided was now focused directly on her.

With Eleanor’s brother funding a professional investigator and the district attorney reviewing evidence, the possibility of arrest became real.

But Catherine had one critical advantage.

The only witness who could definitively prove her guilt was legally prohibited from testifying against her.

The question was whether Samuel would risk everything to ensure justice prevailed.

Marcus Webb’s investigation hit its critical obstacle in September 1858.

Every piece of evidence was circumstantial, suspicious circumstances, suggestive letters concerning patterns, but no direct proof of murder.

Without a witness to the actual deaths, no prosecutor could secure a conviction.

Web needed to find Samuel.

Tracking a freed slave to Philadelphia in 1858 was nearly impossible.

Freed blacks often used false names to avoid recapture under the Fugitive Slave Act.

They moved frequently, worked cash jobs that left no paper trail, and deliberately avoided creating documentation that could be used against them.

But Samuel had made one mistake.

He had kept his real name.

Webb found him working as a teacher in a small Freedman school in Philadelphia’s seventh ward.

Samuel had used Catherine’s money to establish himself modestly, renting a small room, teaching children whose parents scraped together pennies for education, and trying to build a life that didn’t include murder and coercion.

Webb approached him in late September with a proposition, testify about what he witnessed, help convict Catherine Whitmore of two murders, and ensure justice for Eleanor and Margaret.

Samuel’s response was immediate and final.

No.

Webb was stunned.

She murdered two women.

You’re the only witness who can stop her.

I’m also the only witness she’ll believe is dead if I stay away,” Samuel replied.

“The moment I testify, she’ll have me killed.

Free papers won’t protect me from an assassin.

” “You’d let a murderer walk free?” Samuel met Webb’s eyes with a steady gaze of someone who’d survived impossible circumstances through calculated pragmatism.

>> >> I’d let two murderers walk free if it means I survived to teach 20 children how to read.

That’s the mathematics of my life, Mr.

Webb.

You wouldn’t understand.

Webb tried appealing to Samuel’s conscience, his sense of justice, even offering protection he couldn’t guarantee.

Samuel refused every argument.

Finally, Webb played his final card.

Eleanor’s brother is offering $500 for testimony that convicts her killer.

$500 was life-changing money for a freedman in 1858.

It was security, education, business capital, and escape from poverty.

Samuel considered this for a long moment.

Then he asked a question that revealed the true complexity of his position.

If I testify and she’s convicted, what happens to me? Web didn’t have a good answer.

Even with Catherine convicted, Samuel would remain a freed black man who’d accused a white woman of murder.

He’d be a marked target for every racist who believed he’d stepped beyond his place.

“He’d never be safe in America again.

I’ll take my chances with silence,” Samuel said finally.

“Tell Thomas Ashford I’m sorry for his loss, but I won’t die for his sister’s justice.

” Webb returned to Charleston empty-handed.

The Charleston District Attorney, faced with compelling circumstantial evidence, but no witness willing to testify, made a calculated decision.

He would prosecute Catherine Whitmore for fraud and conspiracy rather than murder.

The charges filed in October 1858 alleged that Catherine had conspired with Eleanor and Margaret to violate South Carolina’s laws regarding slave ownership and cohabitation, that she had defrauded Eleanor’s estate through manipulation of the cooperative agreement, and that she had failed to properly report circumstances surrounding Margaret’s death.

The charges avoided the word murder, but implied it heavily.

Catherine’s trial began on November 3rd, 1858, exactly 1 year after Eleanor’s death.

The courtroom was packed with Charleston Society members who had never heard of the cooperative, the house on Longitude Lane, or the arrangement between three widows and an 18-year-old slave.

The prosecution built its case methodically.

estate documents proving the cooperative, testimony from neighbors about suspicious activities, the doctor’s admission that he hadn’t examined Eleanor before signing her death certificate, and Margaret’s maid describing her mistress’s fear before her death.

Marcus Webb testified about his investigation, presenting Eleanor’s unscent letter as evidence of her fear and distress.

The defense attorney, one of Charleston’s most expensive lawyers, countered every point.

The cooperative was unusual but legal.

Eleanor’s letter was vague and could reference any number of concerns.

Margaret’s suicide was tragic, but not criminal, and the entire prosecution was built on innuendo and speculation.

“Where is the evidence of fraud?” the defense attorney demanded.

“Where is the proof of conspiracy? The prosecution has presented you with tragic coincidences and asks you to convict a respectable widow based on suspicion.

” The trial lasted 6 days.

The jury deliberated for 3 hours.

They returned a verdict of not guilty on all charges.

Catherine Whitmore walked out of the courtroom a free woman, her reputation damaged, but her liberty intact.

The judge sealed all trial records, citing the sensitive nature of the testimony and the need to protect the deceased women’s reputations.

Thomas Ashford left Charleston the next day, defeated and furious.

Marcus Webb closed his investigation, convinced he’d witnessed a murderer escape justice through legal technicality.

And in Philadelphia, Samuel read about the trial’s conclusion in a newspaper and felt the complicated relief of having made the right decision for himself, even if it wasn’t the just decision for Eleanor and Margaret.

Catherine returned to her tobacco business, never remarried, and lived another 32 years.

She died in 1890 at the age of 74, wealthy and respectable, having never faced consequences for the two women she murdered.

But the story still had one final chapter.

Justice failed in 1858.

But history has a longer memory than courts.

What happened after Catherine’s acquitt would reveal truths that legal testimony never could, and it would ensure that the three widows story, however dark, would eventually reach the light.

The final chapter explains how sealed court records became public knowledge and what Samuel’s ultimate choice meant for everyone involved.

Katherine Whitmore lived three decades after her trial, managing her business successfully, maintaining her social position, and never publicly acknowledging the events of 1857 to 1858.

But privately, she documented everything.

In a locked trunk discovered after her death in 1890, Catherine’s executive found 17 leather-bound journals covering her entire adult life.

The journals from 1856 to 1859 contained detailed descriptions of the cooperative, the deterioration of relationships, and most shockingly explicit admissions of how she murdered Eleanor Ashford and Margaret Cordell.

Catherine wrote with the cold precision of someone documenting a scientific experiment.

She described purchasing arsenic, calculating dosages, administering poison in tea and wine, and disposing of Margaret’s body.

She explained her reasoning.

Eleanor had become a liability through emotional instability.

Margaret had become dangerous through her documentation efforts, and eliminating both was necessary to protect herself.

The journals also contained Catherine’s assessment of Samuel.

Remarkably intelligent, dangerously perceptive, and ultimately pragmatic enough to value his own survival over abstract justice.

He made the correct choice in refusing to testify.

I would have had him killed within a month of conviction.

Catherine’s executive faced an immediate dilemma.

Publishing the journals would scandalize Charleston society and potentially prompt legal action against Catherine’s estate.

Destroying them would hide valuable historical documentation.

He chose a middle path.

He donated the journals to the South Carolina Historical Society with the stipulation that they remain sealed for 50 years after Catherine’s death.

Those journals were open to researchers in 1940.

By then, everyone involved was dead.

Thomas Ashford had passed in 1902.

Marcus Webb died in 1915 and Samuel had died in Philadelphia in 1923 at the age of 84, having spent 65 years as a free man teaching thousands of children to read.

Samuel never spoke publicly about the cooperative, the murders, or his decision to refuse testimony.

But in 1920, 3 years before his death, he gave a single interview to a black newspaper in Philadelphia.

The interviewer asked if he had regrets about his choices.

Samuel’s response revealed the depth of his understanding.

I regret that two women died.

I regret that a murderer lived free, but I don’t regret surviving.

The white folks who judge me for that decision never had to make calculations like mine.

They never had to weigh justice against a lynch mob.

They never had to choose between speaking truth and breathing tomorrow.

The interviewer asked if he would testify today, decades later, if given the chance.

Today, I’m an old man who taught 5,000 children to read.

Samuel said, “If I testified in 1858, I’d be a dead man who helped convict one murderer.

I think I chose the more valuable path.

” When historians finally accessed Catherine’s journals in 1940, they confirmed everything Samuel never testified to.

The confirmation came too late for legal consequences, but early enough to correct the historical record.

The sealed court documents from Catherine’s trial were also released in 1940, revealing the prosecution suspicions and the defense’s successful strategy of creating reasonable doubt where none should have existed.

Together, the journals and trial documents paint a complete picture of what happened in Charleston in 1857.

Three wealthy widows attempted to circumvent society’s restrictions through an unconventional arrangement.

That arrangement evolved into something legally and emotionally impossible.

And when it collapsed, two women died while the third walked free.

The final accounting.

The house on Longitude Lane still stands in Charleston’s historic district.

It’s been renovated multiple times, serving as a private residence, a law office, and currently a boutique hotel.

No historical marker identifies its past.

Most guests sleep comfortably, unaware that they’re resting in rooms where two murders were planned, and one victim took her last breath.

Katherine Whitmore’s grave in Magnolia Cemetery bears no mention of the trial or the accusations.

Her tombstone describes her as a successful businesswoman and benefactor to several charitable causes.

She donated generously to orphanages and schools during her life, possibly as penants, possibly as reputation management.

Margaret Cordell and Eleanor Ashford are buried in the same cemetery.

Their plots purchased by their families before the full scandal emerged.

Their tombstones describe them as beloved daughters and faithful wives.

Nothing suggests the unconventional choices they made or the price they paid for them.

Samuel has no grave marker anyone has located.

He was buried in a Freedman cemetery in Philadelphia that was later paved over for development.

His name survives only in school records, the single 1920 newspaper interview, and the scattered references in Catherine’s journals.

The mathematics of their story is brutal in its simplicity.

Two women dead.

One woman escaped justice.

One man survived by refusing to pursue it.

Modern scholars debate whether Samuel’s choice represents pragmatism or moral failure.

Some argue he had an obligation to testify regardless of personal risk.

Others contend that demanding a formerly enslaved man sacrifice his life for white women’s justice is itself a form of moral blindness.

The sealed trial documents reveal one more crucial detail.

The prosecution knew about Samuel’s location in Philadelphia.

They chose not to compel his testimony because they understood the legal impossibility of a black man’s testimony against a white woman in 1858 Charleston.

Even if Samuel had agreed to testify, the judge would have ruled his testimony inadmissible.

Samuel’s refusal wasn’t cowardice.

It was recognition of a system designed to ensure his testimony didn’t matter.

What the story reveals, the case of the three widows exposes several uncomfortable truths about antibbellum American society.

Slavery created legal frameworks that made murder possible and justice impossible.

Catherine could purchase another human being, hold him prisoner, and use the law to prevent him from testifying against her.

The same system that enslaved Samuel also protected Catherine.

Wealthy white women occupied a peculiar position in southern society.

Legally restricted in many ways, but practically insulated from consequences for actions that would have destroyed women of lesser means, Catherine’s wealth bought her the best legal defense, social connections that discouraged thorough investigation, and the benefit of doubt that poverty never receives.

The cooperative itself represented an attempt to find freedom within an oppressive system.

The widows tried to create space for intellectual engagement, companionship, and something approaching equality.

But they attempted this within a legal structure built on inequality.

And that structure ultimately destroyed their experiment.

Samuel’s survival required impossible calculations.

Weigh one’s life against abstract justice.

measure personal safety against moral obligation and navigate systems designed to make both survival and justice unattainable simultaneously.

Catherine’s journals were published in 1955 as part of a historical collection examining Antibbellum Charleston society.

The publication sparked debate about historical documentation of crimes versus respect for the dead.

Some readers found the journal’s clinical description of murder disturbing.

Others valued them as rare firsthand accounts of how slavery corrupted moral reasoning.

The journals revealed Catherine’s final thoughts written weeks before her death in 1890.

I regret the necessity of what I did, but not the actions themselves.

Eleanor would have destroyed all of us through her emotional instability.

Margaret would have done the same through her romantic idealism.

I saved myself and in doing so preserved my ability to contribute productively to society for three additional decades.

The arithmetic favors my choices.

This costbenefit analysis of murder reveals how completely slavery distorted moral frameworks.

Catherine could rationalize killing two women by calculating her own future productivity.

A logic that only makes sense in a society that regularly calculated human worth in dollars and labor output.

Samuel’s 1920 interview provides the counter perspective.

Catherine Whitmore measured life in money and productivity.

I measure it in breaths taken, children taught, and mornings waking up free.

By her arithmetic, she made the right choice.

By mine, she died having never understood what it cost.

The final truth.

The story of three widows who bought one 18-year-old slave doesn’t end with justice or redemption.

It ends with complicated survival, unpunished murder, and historical documentation that came too late to matter legally, but just in time to matter historically.

Samuel lived to 84, teaching until the year before his death.

His students included children who became doctors, lawyers, teachers, and civil rights activists in the 1950s and 1960s.

One of his students, James Morrison, became a federal judge in 1967.

At Morrison’s swearing in, he credited a teacher named Samuel, who once told me that surviving unjust systems long enough to dismantle them is more valuable than dying to protest them.

Catherine’s business provided employment to dozens of people, black and white, for 30 years after the murders.

Her charitable donations funded schools and orphanages.

By conventional measures of productive citizenship, she succeeded brilliantly.

But she died alone, unmarried, having murdered two women and lived with that knowledge for 32 years.

Her journals suggest she slept perfectly well despite this, which might be the most disturbing detail of all.

Eleanor and Margaret’s deaths accomplished nothing except removing two women from a world that had already restricted them severely.

Their attempt to find freedom within slavery’s legal framework failed completely, proving that systems built on oppression cannot be reformed from within.

They can only be survived or destroyed.

The house on Longitude Lane contains these ghosts.

Two murdered women, one murderer who died free, and one survivor who chose life over justice because justice wasn’t actually available to him.

Guests staying at the boutique hotel sometimes report feeling uncomfortable in certain rooms, hearing sounds they can’t explain, sensing presences they can’t identify.

The current owners dismiss these reports as typical historic building quirks.

But the discomfort is real.

Some houses remember what happened within their walls, even when the people who walk those halls have forgotten.

In 1857, three widows attempted to purchase freedom through money and unconventional arrangements.

Two died for that attempt.

One killed them and lived free.

One survived by refusing to choose justice over survival.

The story demonstrates what happens when human beings try to build humane relationships within inhumane systems.

The system wins, the relationships fail, and survival requires calculations that destroy a piece of everyone involved.

Samuel understood this from the beginning.

Catherine learned it too late.

Eleanor and Margaret never learned it at all, and that ignorance killed them.

Charleston in 1857 was a city built on the legal fiction that some humans were property.

That fiction created the circumstances for every event in this story.

the cooperative, the murders, the trial, and the sealed records.

When the journals were finally opened in 1940, America was different, but not different enough.

Black Americans still faced legal restrictions, social oppression, and violence for attempting to testify against white Americans.

The specific laws had changed, but the power dynamics remained recognizable.

By 1955, when the journals were published, the civil rights movement was beginning to dismantle some of those structures.

Readers encountered Catherine’s cold costbenefit analysis of murder during the same years that Americans were watching black children integrate schools under military protection.

The parallel was impossible to miss.

The same legal frameworks that protected Catherine in 1858 were still protecting white murderers in 1955.

The same calculations that Samuel made about testifying in 1858 were being made by black witnesses to racial violence in 1955.

The story of three widows and one slave isn’t historical curiosity.

It’s a map of how oppressive systems create impossible choices, reward the ruthless, punish the vulnerable, and ensure that justice remains perpetually deferred for those without power.

Samuel’s choice to value survival over testimony wasn’t cowardice.

It was the recognition that systems designed to prevent justice cannot be fixed by individual sacrifice.

They can only be survived long enough to raise the generation that will dismantle them.

He survived.

He taught.

His students lived to see the Civil Rights Act pass, the Voting Rights Act enacted, and some of the legal structures that protected Katherine Whitmore finally destroyed.

That’s not justice for Eleanor and Margaret, but it’s something.

And for a man who spent 18 years enslaved and 65 years calculating survival odds, something was better than the nothing that testifying would have achieved.

The sealed court records confirm this.

Even if Samuel had testified, the judge would have ruled his testimony inadmissible.

His sacrifice would have meant nothing except his own death.

He chose to live.

History suggests he chose correctly.

The story you’ve just heard has been reconstructed from Catherine Whitmore’s journals, sealed court documents released in 1940, Samuel’s 1920 interview, and historical records from Charleston’s Antibellum period.

The names, dates, and events are documented.

The dialogue is reconstructed from written accounts.

The moral complexity remains unresolved because some historical events resist clean conclusions.

Three widows bought one slave, two died, one killed them, one survived by refusing to seek justice he couldn’t obtain.

That’s the truth of 1857 Charleston.

A city built on legal fictions so complete that murder could hide behind property law and justice could be legally impossible for those most deserving of it.

The house still stands.

The graves remain marked.

The journals exist in archives.

And somewhere in Philadelphia, unmarked and paved over, a freedman rests who chose to teach 5,000 children rather than die testifying against a woman the court would have protected anyway.

History doesn’t always deliver justice.

Sometimes it just delivers truth.

Decades too late to matter legally, but just in time to matter morally.

This was that truth.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load