Two Native Brothers Vanished While Climbing Mount Hooker — 13 Years Later, This Was Found….

They vanished without a sound.

Two brothers, sons of the Wind River Range, wrapped in legacy and rope, disappeared into the granite jaws of Mount Hooker.

It wasn’t sudden.

It was quieter than that.

A silence that grew roots in the community, creeping into dinners, smothering phone calls, settling deep in the bones of the people who waited.

They were strong, experienced native climbers whose lineage stretched back farther than any topographic map could chart.

And then one late summer day, they were simply gone.

13 years later, the mountain gave back a piece of them.

What two modern climbers stumbled upon wasn’t just a forgotten camp.

It was a ghost suspended on a cliff face.

A frozen scene that would reignite a mystery thought buried beneath time and snowfall.

This wasn’t just about gear or a ledge or a body.

It was about brothers.

It was about the silence they left behind and the thunder their discovery would unleash.

The silence had started on a crisp Tuesday morning in August 2011.

At first, it wasn’t cause for concern, just a delay.

Nothing out of the ordinary for a climb of this magnitude.

But by Wednesday, that silence had begun to press in.

Heavy and wrong.

People noticed.

Calls were made.

And in a small reservation community just outside Lander, Wyoming, two families began to understand something that no one wants to understand.

Wasa and Ado Running Wolf were overdue.

The brothers, age 26 and Iene 23, weren’t new to the mountain.

They were raised in its shadow.

Wicasa the elder was known for his discipline.

A man of few words but steady presence.

He had served four years in the army before returning home.

Trading fatigues for chalk bags.

Atto, full of laughter and daring, followed him everywhere.

Where weasa planned, Atau improvised.

Where weasa measured, Atau leaped.

But on the rock, they moved like one body.

Their bond was more than fraternal.

It was survival hardened, forged over years on cliff faces, river crossings, and long winters.

They set out that August with a clear road in mind, the northeast buttress of Mount Hooker, a demanding vertical ascent that few dared to complete without backup.

But the Running Wolf brothers had their system, redundancies, emergency protocols, radios, satellite phones.

Except, as the investigation would later reveal, the satellite phones never made it past the parking lot.

At 6:00 p.m.

that Tuesday, Ado’s girlfriend, Mera Yazzy, waited by her phone.

That was their agreed upon check-in time.

A single message, a text, a photo, anything.

But it never came.

By 8, she was pacing.

Her calls going straight to voicemail.

She told herself it was nothing.

Maybe poor signal or a late finish on the climb.

She tried to sleep but didn’t.

By morning, her fear was hollowing her out.

Meanwhile, Wicasa and Otto’s mother, Leotaa running wolf, was lighting sage in the kitchen.

She didn’t know yet, not fully, but something inside her had shifted.

Later, she’d say it was like a thread being pulled from the inside.

She’d felt it snap sometime around midnight.

That morning, Meera called Leotaa.

Together, they dialed the Wind River Tribal Police, who immediately forwarded the matter to Fremont County.

Sergeant Ron Keller was the first to respond.

A grizzled officer with 20 years in search operations.

He didn’t like the details he was hearing.

Two experienced climbers, both native, both off-grid longer than planned, in a part of the state notorious for devouring people whole.

The moment he heard Mount Hooker and no contact for 36 hours, he pushed the case to high priority.

By noon, he was driving up the long tooth rattling road to the big sandy trail head.

His tires kicked up dust that hung in the air like ghosts.

The forest closed around him, lodgepole pine, and aspen standing in solemn watch.

It was 78°, dry, and silent.

When he arrived, he spotted the truck immediately.

A dusty red Toyota Tacoma parked alone near the edge of the lot.

The windows were streaked with pollen, the windshield edged in gold yellow leaves.

It looked undisturbed.

Keller ran the plate.

It came back registered to Leota Running Wolf.

He approached the cab, opened the door.

The interior was neat.

two guide books in the side pocket, a beaded keychain swinging from the ignition, a bundle of topo maps, and in the glove compartment, like a cruel joke, were two satellite phones.

Fully charged, unused.

He called it in with a low voice, masking the sharp edge of worry in his gut.

Found the vehicle.

Two satones inside.

Looks like they never left with them.

That single fact flipped the theory on its head.

This wasn’t just a delay.

This was a blunder that didn’t fit the profile.

Wikasa didn’t make mistakes like that.

Within hours, the trail head bloomed into a makeshift command post.

Search and rescue units rolled in.

Maps were spread out on hoods of trucks.

Routts were drawn and redrawn.

Helicopters were called.

Ground teams were assembled.

The Wind River Range was carved up into sectors, grid by grid.

The next morning, choppers buzzed across the sky, eyes scanning every ridge and ravine, but they found nothing.

3 days in, the weather turned.

A rogue storm swept down from the northwest, swallowing the peaks in a cold fog.

Rain gave way to sleet.

Sleet to snow.

Search flights were grounded.

Ground teams slipped and faltered across the slick granite.

The S commander made the call.

pull back.

It was no longer safe.

Wicasa and Otto, wherever they were, would have to wait.

But their friends wouldn’t.

By the weekend, a group of native climbers, friends, cousins, community, arrived with their own ropes, their own gear, their own knowledge.

They called themselves the Crows.

Not official, not government approved, but seasoned, skilled, and intimate with the terrain.

Some had climbed with Wicasa.

Some had grown up with Otto.

They weren’t searching for strangers.

They were looking for their own.

The crows moved differently, instinctive, flexible, reading the land like a second language.

They ignored the grids, searching hidden ledges, obscure approaches, and undocumented routes weasa had once mentioned in fireside conversations.

They poured over his old journals, searching for hints, notes in Lakota, sketches of ridge lines, marks that meant something only to those who knew him.

For 9 days, they combed the range.

Found nothing.

No dropped gear, no tent shreds, no food wrappers, not even a bootprint.

By the 10th day, hope had thinned to a thread.

The official command post packed up.

The crows descended in silence.

The mountain, silent as ever, gave back nothing.

And for the next 13 years, the running wolf mystery hung like mountain mist, thick, cold, and impenetrable.

Back in Lander, Leotaa waited.

Every season, passing her window felt like another unanswered knock.

She kept the boy’s room untouched.

Otto’s hoodie draped over the back of a chair.

Wikasa’s boots lined against the baseboard.

The scent of sage hung in the air, blending with dust.

She never said goodbye, only waited for the wind to speak.

The reservation held its breath for years.

The running wolf case became both taboo and sacred, spoken of in hushed tones, referenced by hikers, feared by locals.

Every so often, someone would claim they’d found something.

a jacket scrap, a length of rope, but nothing ever confirmed.

Fremont County moved the file to cold storage.

The world moved on.

Then in the summer of 2024, a pair of young climbers, digital age athletes armed with GoPros, ultraight gear, and satellite weather feeds, showed up at Mount Hooker’s southern face.

They weren’t interested in repeating old clims.

They were there to carve a new route on a face so sheer it looked like a blade.

Nobody climbed that wall, no record of it, no name.

They were halfway up the pitch on the second evening, the sun beginning to drop behind the granite spires when the lead climber spotted something strange.

A bolt, rusted, old, not in any guide book, not in any beta.

More appeared as he climbed.

a sequence of weather-beaten hangers leading sideways toward a shadowed al cove.

They followed.

They weren’t sure why.

Maybe curiosity, maybe exhaustion.

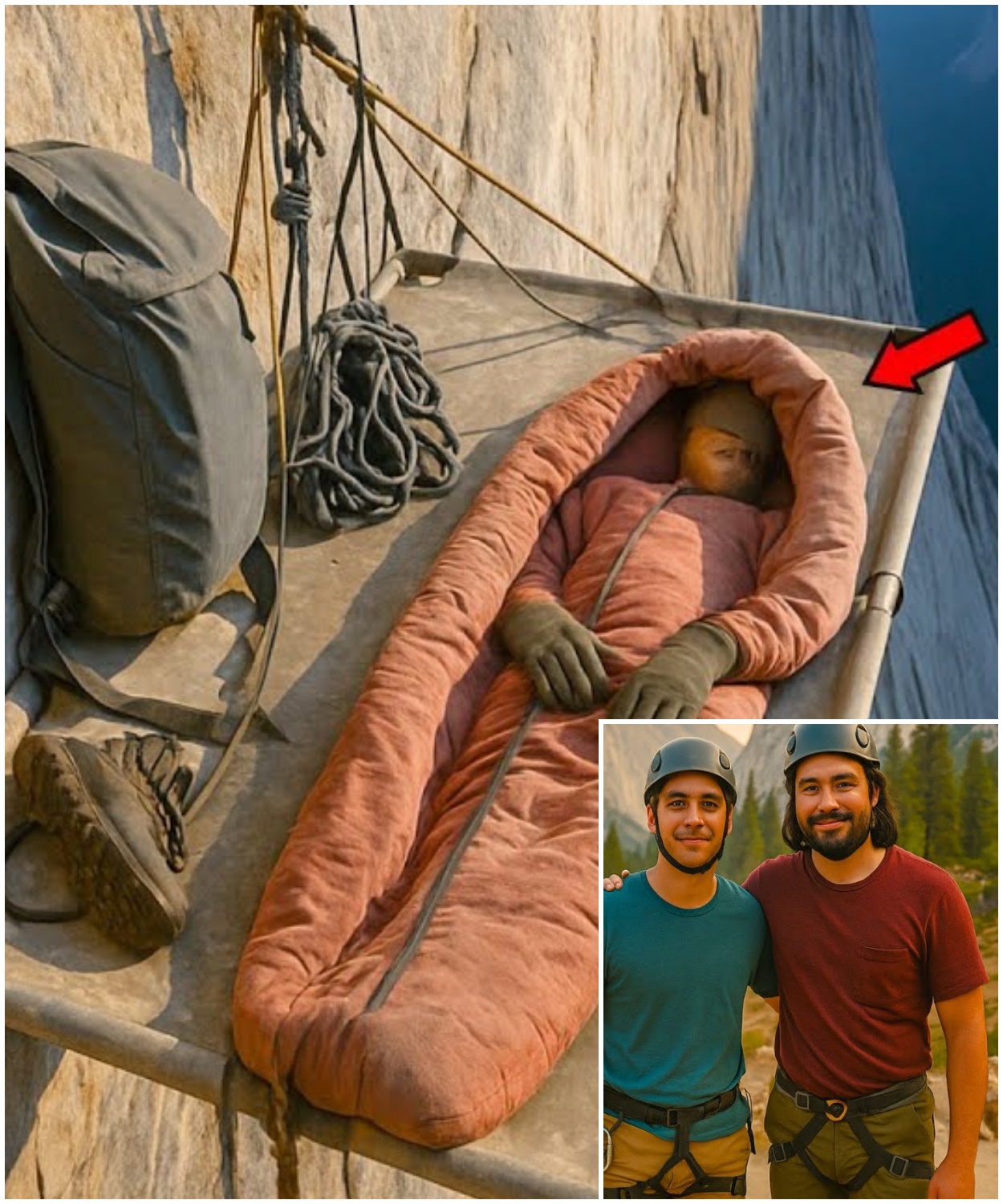

But the al cove revealed something that should not have been there.

A portal ledge suspended like an ancient relic.

Faded fabric, coiled rope, a blue dry bag, a red sleeping bag.

All of it frozen, eerily orderly, as if someone had left just moments before.

But the fabric told a different story.

Bleached by sun, stiff with age.

The lead climber, hands trembling, reached for the zipper on the bag.

The pull tab resisted, then gave.

Inside lay a skull, bleached clean, resting on bundled fleece like a makeshift pillow.

A scream echoed across the mountain.

And just like that, the running wolf case was back.

The scream fractured the quiet of the cliffs, bouncing off granite like a warning bell that had been waiting 13 years to ring.

The young climber, Ethan Darrow, was frozen in place, fingers still clenched around the zipper.

The skull stared up at him with empty sockets, nestled like a secret in the red sleeping bag.

Just below him, his partner, Milo Chen, was already moving, climbing quickly but carefully to reach the al cove.

unaware of what awaited.

When he got there, the look on Ethan’s face stopped him cold.

“What is it?” he asked, though he could already feel the weight of the answer.

Ethan’s voice cracked, barely above a whisper.

“There’s a body in the bag.

” A rush of adrenaline made everything sharper.

Milo followed Ethan’s eyes and peered into the sleeping bag.

The skeletal face met his gaze, unblinking.

It didn’t look posed or accidental.

It looked intentional, secured to the portal edge with care, protected from the wind, anchored down with thick, weatherworn webbing.

This wasn’t a gear dump.

This was a tomb.

Neither of them spoke for a moment.

The wind gusted, flapping the faded edge of the tarp, and with it came the smell.

Not rot, not decay, just cold stone.

old nylon and time.

They knew the protocols.

Both had completed advanced rescue training.

You didn’t disturb a site like this.

You didn’t move gear.

You didn’t touch remains.

Milo pulled out his phone and began snapping photos.

Every angle, every bolt, every shadow.

Ethan retrieved his own device and dropped a GPS pin, praying it would save.

Despite the lack of service, it was unlikely they could transmit anything until they were well below the tree line.

The descent was slow.

They were careful, silent.

Every repel, every anchor was executed like a ritual.

The image of the skull hovered behind their eyes no matter where they looked.

The gear was too old.

The setup too deliberate.

Someone had tried to protect that body.

Someone had left it like that, likely knowing they wouldn’t return.

By the time they reached the base, night was falling, and their muscles were shaking with exhaustion.

They bivowacked under a rock overhang, watching the stars blink into view above the treetops.

Neither of them slept.

The mountain had become something different.

No longer just an adventure.

Now it was a grave.

The following morning, they stumbled out of the alpine forest and into the Big Sandy trail head parking lot, where Ethan finally got a bar of service.

His call to 911 was short, clipped, factual.

The dispatcher asked him to repeat it three times before it registered.

You’re saying you found a body on Mount Hooker? Yes.

On a portal edge, cliffs on the south face.

It’s old.

How old? Ethan exhaled.

Feels like forever.

The report rocketed through the Fremont County Sheriff’s Office within hours.

The name running wolf was spoken aloud in the squad room for the first time in years.

It cut through the air like the reappearance of a ghost.

Files were pulled from deep storage.

Photographs laid out.

A map unfurled across the conference room table.

Detective Lily Menddees was assigned to the case.

Newly transferred to the cold case unit, she had grown up hearing whispers about the brothers who had gone up the mountain and never come back.

Her uncle had known them.

Her mother had once served food to them at a pow-ow fundraiser.

For her, this wasn’t abstract.

This was home.

She drove straight to the base camp where Ethan and Milo had agreed to meet investigators.

They were pale, wired, still jittery with the weight of what they’d found.

They showed her the photos, the portal edge, the webbing, the sleeping bag, the skull.

Menddees listened carefully, scribbling notes, barely blinking.

When they showed her the GPS coordinates, she whistled under her breath.

It wasn’t near any known route.

No established line passed through that section of cliff.

If a portal ledge was there, it meant someone had made their own path or been forced to change course.

2 days later, the recovery team began their operation.

It wasn’t simple.

Aerial support was limited by winds.

The cliff face offered few anchor points.

The site was accessible only by technical climbers with vertical extraction gear.

The sheriff’s office called in the elite rescue unit from Grand Teton National Park, specialists in high angle recoveries.

Alongside them was a forensic anthropologist from the University of Wyoming, Dr.

Paulina Estz.

She was there not just to examine remains, but to observe the site itself.

In her line of work, context was everything.

the way a sleeping bag was folded, the position of a carabiner, what was left behind and what wasn’t.

The first team ascended two days after Ethan’s call.

They anchored above the al cove, then repelled down to the portalage in a slow, deliberate stages.

Everything was filmed.

Body cameras captured the exact orientation of every piece of gear.

The dry bag, the rope, the sleeping bag.

The sleeping bag was still fastened to the portal edge frame, secured with two lengths of nylon cord tied with climber’s knots.

Dr.

Estavis’ voice came through on the radio.

That’s intentional, protective.

Whoever left her, if it was a her, didn’t want her to fall off.

They moved carefully, cutting the cords only after fully stabilizing the bag in a transport stretcher.

They examined the coil of rope, faded, but intact.

A climbing nut still jammed into a crevice, its anodized color long since eroded.

The dry bag contained little, a broken water filter, some crumbled freeze-dried food packs, and a battered first aid kit that had clearly been used.

Once back on the ground, the remains were transferred to the state crime lab.

It didn’t take long to confirm what everyone feared and expected.

The body belonged to At Running Wolf.

The confirmation hit the reservation like a landslide.

For years, people had debated if they were alive, hiding, trying to escape.

Others believed they’d simply fallen into a creasse or been lost to wildlife.

But now, one answer had arrived.

The younger brother Atau had died on that cliff alone and anchored to the rock.

But even that discovery raised more questions.

Why was only Atau found? Where was Wicasa? Why had Atau’s body been placed so deliberately, protected from the elements, anchored as though someone had every intention of returning but never did? Then came the fracture.

During the autopsy, Dr.

Davis found something critical.

Otto’s right femur was shattered, a complex spiral fracture with deep splintering.

She noted additional damage along the lower tibia, likely from impact.

Her conclusion was clear.

Otto had suffered a catastrophic leg injury, likely during the climb.

He wouldn’t have been able to walk.

He wouldn’t have been able to descend on his own.

He had been stranded.

and someone had placed him in that bag, tied him down, and left him with supplies that someone had to be Wasa.

Detective Menddees stared at the board in her office, photos of the ledge, the body, the gear.

There was no sign of struggle, no trauma inconsistent with a fall, no second body.

One harness was missing.

Wicassas.

One set of footprints must have walked away from that ledge.

But to where? They reviewed everything.

Old search maps, terrain models, weather logs.

Menddees called in Alan Greyhawk, a childhood friend of Wasa, and one of the crows who had searched the mountains 13 years ago.

Alani walked the maps like a memory.

She traced possible descents with her fingers.

Her eyes narrowed.

Then she stopped, tapping a ridge line just southeast of the portal ledge.

If he was going for help, he’d take this chute, direct line, fastest way to the tree line.

Menddees gave the order.

Another team was assembled.

A forensic climb down the proposed route, searching for anything.

Anchors dropped gear, footprints etched into stone by time and ice.

The next day, about 400 ft below the ledge, they found it.

A single python jammed into a micro crack near a narrow gully.

It was rusted, worn smooth by wind and rain, but it was old school, the kind Wicassa preferred.

Nearby, a faint smudge on the rock, magnesium chalk, faded almost to nothing.

He had been there.

Hope surged.

If he’d passed that way, perhaps he’d made it down.

Perhaps he was still alive, living somewhere else.

Maybe he had gotten lost, injured, disoriented.

Or maybe something worse.

The search team expanded their grid.

Drones were dispatched.

A new round of highresolution imagery began, but again the trail vanished into stone.

Wicasa had descended from that ledge.

Of that there was no doubt.

But where he had gone, what had become of him, remained sealed behind stone, cloud, and time.

Hope, like altitude, can be deceiving.

One moment it fills your lungs with purpose, the next, it leaves you gasping against the silence.

For the Running Wolf family, the discovery of Otto’s remains was both a revelation and a new wound.

After 13 years of questions, at least one had been answered.

But the cost of that answer, the finality of it, landed heavy in their home like the fall of granite.

And it came with a second colder realization.

Wicasa was still missing.

Leota Running Wolf didn’t cry when they told her.

Not immediately.

She had cried every night for over a decade.

What she felt instead was a strange clarity, like fog lifting from a distant peak.

I knew he didn’t leave Otto, she said quietly, her voice steady.

He stayed until he couldn’t.

That had always been her fear, buried deep beneath the weight of uncertainty, that they had died alone.

But now she knew Otto hadn’t died alone.

His brother had been with him, cared for him, anchored him to the rock, and left him only because there was no other choice.

But the question of what happened to Wicasa bore into everyone like an unrelenting storm.

Where had he gone? Why hadn’t he made it to help? If he had survived long enough to anchor his injured brother in place, why was there no further sign of him? Why had the mountain erased his path? Detective Menddees couldn’t let it go.

She revisited the old search logs, transcripts, SR debriefs, and even rumor boards from the early days.

One particularly faded record from the original operation mentioned a theory proposed by a search coordinator at the time, an alternate descent route that cut southeast across a series of narrow gullies before terminating in a sheer drop off.

The route was dismissed back then as too exposed, too improbable.

But if Wicasa had been desperate, if time was bleeding away from Ata with every hour, it was the kind of risk he might have taken.

The topographic model showed a terrain feature, a box canyon surrounded by vertical granite on three sides about 3 mi southeast of the portal ledge.

There were no trails into it.

No reason for anyone to go there.

It was quite literally off the map.

Menddees called in a geospatial drone survey team.

They used thermal and infrared imaging, scanning every crack and ledge of the canyon basin.

At first, nothing stood out.

Then, late on the third day, a technician spotted something irregular.

A patch of blue gray amidst the tan of lychencoed stone.

The drone zoomed in.

There, half buried in scree and windb blown dust, was a strip of fabric shredded, fluttering faintly in the breeze.

The drone’s camera panned.

A few meters away, scattered among fractured boulders, were white fragments, irregular in shape, too pale to be rock.

The technician didn’t speak.

He simply pressed, “Pause,” then whispered, “We’ve found him.

” The recovery was even more difficult than at there was no landing zone.

The helicopter team had to winch down rescue personnel in pairs, dangling above the sharp rocks before dropping into the basin like careful ghosts.

What they found was devastating.

The remains were scattered, fragmented, and weatherworn.

Bones partially buried in sediment.

Others displaced by wildlife.

The windbreaker, once vibrant blue, was now a sunbleleached rag tangled in roots.

But what stood out wasn’t the fragmentation.

It was what was found near the skull, a gleam of metal, a titanium plate.

It had been surgically implanted along the jawline, fused to bone.

Dr.

Estavves later confirmed it with full certainty.

It matched Wikasa’s medical records.

15 years earlier, he had shattered his jaw in a motorcycle accident and undergone reconstructive surgery.

The model and serial number of the plate left no doubt.

We causing wolf had been found.

The grief hit the community in waves, candle vigils, drumming circles, old men and women weeping quietly into cupped hands.

The crows, the same climbers who’d searched in 2011, held their own ceremony at the trail head, burning sage and offering tobacco, whispering weasa’s name into the mountain wind.

But for Detective Menddees, the final discovery was not enough.

She needed to know what had happened in those last hours.

What had brought Wasa to that canyon? Why had he fallen? Why hadn’t he made it out? Dr.

Estavis’s team reconstructed what they could.

The location of the body, the angle of the boulder impact, the pattern of fractures.

Their best estimate, Wesa had descended too far, possibly in a storm or at night, lost his footing on slick granite, and fallen nearly 60 ft into the basin.

The injuries were catastrophic, broken ribs, pelvis shattered, skull trauma.

They believe he survived the fall, if only for a short time.

Near the remains was another detail that gripped Menddees.

A single carabiner looped through a short length of cord attached to a climbing journal.

It had somehow survived.

The cover was curled and brittle, but the pages inside, protected by the waterproof casing, were still legible.

Inside were only a few entries, scribbled, rough, but one stood out.

Just five words.

Still alive.

Hold on.

There was no signature, no date, but the page bore smudges of blood.

Menddees closed the book and stared out at the granite walls surrounding her.

The investigation was done.

The mystery had resolved not into scandal or conspiracy, but something far more devastating.

Two brothers had faced the mountain together.

One had been injured, the other had tried to save him, and the mountain had taken them both, one slowly, the other all at once.

Back on the reservation, Leotaa received the journal in person.

Menddees handed it to her without a word.

The mother turned it over in her hands, then opened to the last message.

She read it once, twice, then she closed it, pressed it to her chest, and whispered her son’s names.

There would be a memorial, not in a cemetery, but in stone.

At the edge of the Big Sandy trail head, a carved cedar post now stands, facing Mount Hooker.

It bears no grand inscription, only the brother’s names, a medicine wheel, and the words, “He anchored his brother.

He never let go.

By the time the final reports were typed and filed, the mountains had already reclaimed their silence.

Summer had turned just slightly toward fall.

The wind had a new edge to it, sharper than before, whispering through pine needles and over granite cliffs.

But for those who had followed the case, those who had lived in its shadow for 13 long years, something had changed.

Not the place, not the mountain, but the air itself.

As if the Wind River Range, having held its secret for so long, had finally exhaled.

Detective Lily Menddees sat alone in the Fremont County archive room long after the lights had dimmed.

The case files spread out before her.

Hundreds of pages, maps, drone footage, forensic diagrams, autopsy reports, transcripts of interviews dating back more than a decade.

She flipped through them slowly, methodically, then paused at a photo of the portal edge.

The fabric was torn, the gear sunbleleached, but the structure remained remarkably intact.

It wasn’t luck, it was deliberate.

Wicasa had made that ledge into a fortress for Otto, for time, for memory.

And yet, as complete as the case now seemed, one question persisted.

Not from the recovery site, not from the canyon where Wakasa had fallen, but from the beginning back at the trail head all those years ago.

Why had they left the satellite phones in the truck? It was the smallest detail, easily missed, easily rationalized, but it was also in some ways the first step toward tragedy, the failure point, the route.

Menddees reopened the original photo taken by Sergeant Keller in 2011, the dusty red Tacoma, the cracked windshield, and inside in the glove compartment, two satellite phones, fully charged, functional, and unused.

The forensic report showed both devices had no activity logged.

They were simply never turned on.

She had considered early in the new investigation that it might have been an oversight, a mistake.

But the more she learned about Wicasa, his precision, his preparedness, his methodical nature, the less likely that seemed.

He would never have left without those devices unless he meant to.

So the question clawed at her.

Was it possible they had left them behind on purpose? She returned to the journal recovered near Huicesa’s body.

It was only partially filled, most of it blank pages, but a few scrolled lines, faded ink, and trembled words hinted at something more.

One page just before the final note about Otto contained a sentence written at an angle, squeezed into the margin.

No tech, clean ascent.

We do this like they did before.

Menddees leaned back in her chair, the hum of the archive room settling around her like snow.

She read the line again.

No tech.

Could it be that simple, that deliberate? A choice, not born of recklessness, but of reverence.

She called Alani Greyhawk the next morning.

Was there ever any talk? Menddees asked about the brothers wanting to climb clean.

There was silence on the other end, then a long thoughtful breath.

Yes, Elani said.

Not often, but Wakasa.

He talked about doing a full old style ascent.

No satones, no digital backups, just ropes, instinct, and trust.

He thought the mountain should be met on its own terms.

No interference.

Even knowing the risk, he believed the risk was the point.

The climbing was supposed to be a dialogue with the mountain, not a negotiation.

Menddees didn’t reply.

She was thinking about the words in the journal.

We do this like they did before.

There was no vanity in it, no arrogance, only a desire to step into something ancient, something sacred.

That perspective changed everything.

It reframed the decision at the trail head not as a mistake, but as a vow, a commitment to climb clean, to trust each other, not the signal from a satellite.

And it made what followed not just a tragedy, but a kind of pilgrimage, one cut short, not by ignorance or negligence, but by the brutality of nature and time.

Later that week, Menddees met Leotaa Running Wolf at her home.

It was the third time since the recovery, and each visit had taken on the feeling of ritual.

The house smelled of cedar and sweetg grass.

Photos of the brothers lined the hallway.

In one, they stood grinning on a granite ridge, arms slung over each other’s shoulders, their faces bright with sun and altitude.

It was dated 4 months before they vanished.

I wanted to ask you something,” Menddees said gently.

“Do you know if they made a choice not to bring the satones?” Leota looked at her for a long time.

Then she nodded once.

“They didn’t forget,” she said.

“I remember standing at the tailgate.

” Otto asked about it, and Micasa said, “If we’re going to do this, we do it clean.

” He called it a ceremony.

Menddees’s throat tightened.

Why didn’t you tell anyone before? Leota shrugged.

Would it have changed anything? People already thought it was foolish.

Maybe it was, but I understood what he meant.

Some things are supposed to be hard.

Sacred things, especially.

That night, Menddees added one final note to the case file, a handwritten addendum, not for official records, but for memory.

She included the journal quote.

She recorded Leota’s words and she ended it with a line of her own.

They didn’t forget the satellite phones.

They left them behind because they remembered everything else.

Word spread slowly across the climbing community.

The forums that had once speculated wildly about the brother’s fate now filled with tributes, reflections, and reverent silence.

A memorial route was proposed by the same climbers who had discovered Otto’s camp.

They named it Two Anchors.

The climb followed the newly documented bolts leading to the al cove and from there traversed upward, where they believed Wicasa’s solo descent had begun.

Climbers were warned it wasn’t safe.

It wasn’t meant to be.

But it was beautiful and difficult and honest.

The route was added to only one climbing database with a single line of description.

Do not take this climb lightly.

This is not a sport route.

This is a story.

Climb it only if you’re willing to listen.

Months passed.

The snow returned.

The ledges disappeared beneath white sheets.

The portal edge, now recovered, was donated to a small museum in Lander, where it was suspended from a cedar beam, just as it had once hung from granite.

Below it, a plaque bore the story, brief, sparse, respectful.

Children visiting the exhibit stood quietly, staring up at the strange contraption floating above them, their voices hushed.

At the ceremony for the exhibit’s opening, Leota stood beside the display and placed a braid of sweet grass along the edge.

Then she whispered something in Lakota and walked away without looking back.

That night in her dreams, she saw her sons again.

They were standing on a ridge, backs to the wind, arms around each other, laughing, and this time they turned to wave goodbye.

Autumn draped itself over the Wind River Range like a worn blanket, rich with color, but edged in cold.

The trees turned amber and rust.

The air sharpened, and the light began to stretch long across the ridges.

The mountains, for all their hardness, seemed to pause in that season, as if acknowledging what had passed.

The story of the Running Wolf brothers had returned to the land, not as a mystery now, but as memory.

Yet even memory, when stirred, can echo.

Detective Menddees wasn’t ready to let go.

The official case was closed, its boxes packed, its files archived, its timeline secured, but she kept a private notebook tucked in the bottom drawer of her desk, labeled only with the brother’s initials.

Inside were questions not suited for reports, not suspicions, just spaces where the human heart still wandered.

She would drive sometimes out toward the trail head, not for duty, just to sit at the edge of that clearing where their truck had once been.

The lot had changed.

More signage, a newer ranger kiosk, but the view remained the same.

Pinecovered ridges rising like dark green waves.

The first snow already dusting the peaks.

Wind.

Always the wind.

One afternoon, a ranger who’d been on rotation that season came up beside her.

His name was Eli Thomas, a wiry man with a walking stick he had carved himself in a voice that moved slow as thaw.

He asked if she was there to hike, and when she shook her head, he didn’t press.

He only said, “Funny, isn’t it? This place changes everyone who passes through, but it never changes itself.

Menddees glanced at him.

You were working when they disappeared, right? He nodded.

I was the one who logged their permit.

A long pause.

They came through like they belonged here, not just because they were local, though they were.

It was more than that.

Like they knew the stone the way old trees know the soil.

She looked at him.

Did anything seem off? Eli stared at the mountains for a long while before answering.

They were quiet, focused.

Wakasa signed the book, but at he was the one watching the clouds, like he could already hear something coming.

He paused, then said something strange.

Sometimes I think the mountain knew them.

Menddees didn’t ask what he meant.

She just wrote it down later in her notebook, underlined it.

The mountain knew them.

The phrasing had a mythic flavor, but in this place, myth had always lived just beneath the surface of stone and wind.

The reservation was quieter now, but not in the empty way it had been during the years of absence.

Now it was the hush that follows ceremony.

People lit candles on anniversaries.

Climbers left offerings at the memorial.

Elders who had once refused to speak of the boys in the present or past began sharing stories again.

At a community event in early November, a circle of friends gathered around a fire pit behind the tribal center.

Smoke rose slow and blew into the dusk.

An elder named Marjorie White Elk, who had known Wicasa as a child, leaned into the group and said softly, “They were meant to remind us.

” Of what? Someone asked.

Marjgerie smiled.

“That even the strong need help, and that even when help doesn’t come, love can anchor you in place.

” No one spoke for a while after that.

Back in Lander, a regional podcast producer named Joel Ser requested permission to do a special episode on the brother’s story.

Menddees was skeptical at first.

She had seen too many sensationalized accounts, too many twisted facts, and attention-grabbing thumbnails.

But Joel came with reverence, not ego.

He spent months interviewing friends, S climbers, even Leota, who allowed only a single recorded conversation.

The episode released in late December was titled The Anchor and the Ascent.

It opened with the sound of wind blowing across rock, followed by a soft single line in Wicasa’s voice, pulled from a forgotten climbing video found by a family friend.

Sometimes you don’t climb to conquer, sometimes you climb to remember.

The episode didn’t just tell the story of their disappearance and discovery.

It dug into their childhood, long afternoon scrambling up foothills, teenage years navigating grief after losing their father, the growing pull of the high peaks.

It talked about their choice to climb clean and what that meant, not just as a stylistic commitment, but as a cultural act, as ceremony.

Listeners were moved.

Donations came in for a scholarship fund Leota had quietly established at the local high school designed for native students interested in outdoor leadership, environmental science, or traditional lifeways.

It was named for both brothers.

But perhaps the most unexpected reaction came from a different direction.

A mountaineering historian named Camille Reyes based in Colorado reached out after hearing the episode.

She had spent her career studying undocumented ascents and lost routes, especially those that never made it into the climbing community’s official narratives.

After listening, she became convinced that Wicasa and Atau had completed a line no one else had ever attempted, that their ascent, though never fully mapped, represented a level of commitment, risk, and technical skill worthy of the highest recognition.

Camille began compiling notes, piecing together their likely path using drone data, gear remnants, and the climbers’s own journals.

her hypothesis that they had not only pioneered a new route but had done so in conditions that would have turned back most others.

She submitted her findings to the American Alpine Journal.

In June 2025, the Brothers Route, informally dubbed Two Anchors, was officially recognized as a historic ascent.

The accompanying article detailed their gear, their route markers, the conditions, and the cultural significance of their climb.

The climbing world took notice, not because the line was the most difficult or the most famous, but because of the story stitched into its holds.

Two brothers, a sacred vow, a silent fall, and a tether that held even in death.

A ceremony was held the following month at the base of Mount Hooker, hosted jointly by members of the tribe, local SAR teams, and a small group of climbers who had volunteered to maintain the memorial site.

Leota was there.

So was Menddees, and so was Camille, who read from the final paragraph of her article.

They didn’t summit to stand above the world.

They climbed to meet it face to face.

One stayed and one fell, but both left a path behind.

Afterward, a group of young native climbers took to the ridge, carefully, respectfully, tracing part of the original route with newer, safer gear.

They stopped short of the portal ledge, choosing instead to sit on a nearby shelf, looking out at the horizon.

No photos, no talking, just breath, just wind.

In the years to come, more would come.

Some to climb, some to remember, some just to stand in the quiet and let the mountain speak, and sometimes when the air was just right, the sound of rope brushing granite or a carabiner clicking into place would echo down the cliffs, and feel for a moment like the laughter of two brothers carried on the wind.

Winter came quickly that year, burying the peaks in silence.

Snow curled across ridgeel lines, muffled the forest floor, and glazed the portal ledge in layers of ice no sun could fully thaw.

The Wind River Range held its breath once again, not in mourning this time, but in remembrance.

And though no footprints scarred the Alpine passes, no calls echoed from the walls, the brothers presence remained, etched into the stone, suspended in the stories that now flowed like tributaries through the community.

In Lander, inside a modest office above the old post office building, Camille Reyes continued her work.

She was compiling what she called a silent archive.

Not just technical records of undocumented native ascents, but oral histories, family photographs, annotated maps with paths only ever walked once.

The Running Wolf Climb had unlocked something larger.

The realization that so many stories, clims, roots, and risks had lived and died in the margins never recognized because they didn’t fit the structure of what was expected.

With help from Leotaa and several tribal elders, Camille began assembling accounts that had long been passed around in fragments.

The uncle who had climbed unnamed spires in the 60s with hemp rope and homemade pyons.

the cousin who taught her brother glacier navigation using the stars and the tilt of moss on stone.

None of these feats had ever made it into alpine databases or published reports, but they were there in memory, in tradition, in the names whispered for cliffs that didn’t appear on any USGS map.

She called the project mi, water is life.

But the deeper meaning, she said, was movement.

Climbing not as conquest, but as communion.

One night in January, a heavy snowstorm blew through Fremont County.

Winds howled down from the divide, rattling windows, blanketing everything in white.

Power flickered, cell towers faltered, and the town of Lander folded inward on itself like a bear into its den.

At 2:47 a.

m.

, Detective Lily Menddees sat awake in her apartment, wrapped in a blanket, staring at the corner of her wall where she had hung a photo of the brothers taken years ago on a sunny Craig near Sinks Canyon.

They were young, sweaty, laughing.

Otto had his arm slung over Wesa’s neck, his hand flashing a peace sign toward the lens.

They looked like every set of brothers ever born.

Full of competition, full of mischief, full of love.

Her eyes were tired, but she couldn’t sleep.

There was something still unresolved.

Not officially, not legally, but in the way that matters most, in the rhythm of memory.

She rose, poured a glass of water, and pulled out her notebook, the one marked only with their initials.

She flipped past pages filled with technical notes, terrain sketches, satellite timestamps.

Toward the back, she had started recording dreams, strange symbolic ones.

She didn’t know if it was useful, but something in her told her to keep track.

One entry read, “Saw them both on a ledge above the treeine.

” Otto sat with his legs stretched straight.

Wasa standing beside him, pointing down the valley.

They weren’t afraid, just waiting.

Another, a week later, heard rope snapping in the wind like drum beats.

Then silence, then thunder.

Woke up crying.

She didn’t understand them.

Didn’t try to.

But they grounded her in a truth she couldn’t quite explain.

The mountain hadn’t taken the brothers.

It had held them.

Spring approached slowly.

The snow retreated inch by inch.

Melt water surged through creeks, carving veins into the valley floor.

Flowers began to push through frostbit bitten ground.

And up high, beneath layers of ice, the path the brothers had carved reemerged.

Not fully visible, but present.

A shape in the stone.

A memory retold.

In April, a new climbing team arrived, young, local, native.

They’d spent the winter training, not just in gyms and wilderness courses, but under the guidance of the crows.

They weren’t aiming to recreate the brother’s ascent.

That route, they said, belonged to them, but they wanted to honor it.

Their plan was simple, to establish a neighboring line, one that would mirror the original route without touching it.

They called it echol line.

For days they studied the wall, watched it in the morning light, waited for the snow to loosen its grip.

When the time was right, they climbed.

Not fast, not reckless, just steady, with intention.

They placed new bolts only where necessary, anchored with care.

At one point, near the al cove where Otto had once laid, they paused.

They didn’t look in, didn’t intrude.

Instead, they tied a strip of cloth to a small outcrop, braided with red and white beads.

Then they moved on, eyes forward.

The climb took 3 days.

They reached the summit on the morning of the fourth.

The sky was clear, blue, endless.

No shouts, no cheers, just stillness, and a single eagle gliding along the thermals.

They left a can, a feather, and a page from a journal that read, “We remember we’re still climbing.

” Back home, Leotaa kept her routines.

Tea in the morning, tobacco at the window.

Her son’s rooms remained untouched, though she no longer avoided them.

Sometimes she sat on Otto’s bed and flipped through his sketchbooks, half-drawn gear designs, root names he had never used.

Wikesa’s shelf still held his field guides lined in descending order of publication date.

But one morning she packed two small canvas bags with the items most important to her.

Into she placed his climbing harness, now sunfaded but intact and a photo of him as a boy holding a turtle at a summer creek.

into Wicassas.

She placed his field compass and the small cloth pouch that had held his father’s medicine stones.

Then she drove to the tribal office and handed both to the cultural preservation coordinator.

For the archive, she said.

The coordinator nodded, understanding immediately.

These were not donations.

They were anchors.

Later that spring, a traveling exhibition opened in Cheyenne called the vertical memory.

Indigenous presence in America’s highest places.

At its center was a replica of the brother’s portal ledge suspended midair within a darkened chamber lit by a single beam.

Visitors stood quietly beneath it, reading the story on the wall.

One paragraph stood out.

This was not a failed descent.

It was a complete one, not defined by summit photos, but by what was left behind, care, courage, and a path.

By summer, Camille Reyes had turned her silent archive into a foundation.

Grants were issued.

Field programs launched.

Story gathering trips began across tribal lands and remote climbing regions.

The name Yini Choni appeared on chalk bags, water bottles, harness loops, and always somewhere in the distance, the name running wolf lingered like the sound of wind across a cliff face.

Familiar, eternal, carried forward.

Because some stories are never meant to be finished, only passed on.

The morning sky over Mount Hooker was a pale blue sheet torn with streaks of wind scattered cloud.

The kind of sky that makes you feel small in the most sacred way.

Below it the stone watched in silence, immovable and unchanged.

And yet something was different.

Not in the cliff or snowmelt or treeine, but in the people who now stood at its feet.

They came not as conquerors, not as tourists, but as witnesses.

That summer, for the first time since the brother’s disappearance, a formal tribute climb was organized by the Wind River Outdoor Alliance.

It wasn’t advertised.

There was no fanfare, just an email chain between climbers, say our veterans and members of the Crow Crew, and the simple phrase, “We return together.

” The purpose wasn’t to reach a summit.

It was to retrace the path, to place new anchors where needed, to clear brush from the lower approach, to mark the beginning of the trail that led to the portal ledge and beyond.

For a week, the small team worked in pairs, rising early, moving slow, resting often.

They spoke little.

Most of what needed saying had already been said in silence years ago.

On the fourth day, they reached the ledge.

The rock surrounding it was still marked faintly by the scars of sun and lyken.

And though the original portalage had long since been removed, the al cove remained exactly as it had been, tucked away, shielded, reverent.

They didn’t step inside.

Instead, they stood nearby, removed their gloves, and placed their palms against the granite.

A moment passed, then another, and then they moved on.

Back in Lander, Leotaa Running Wolf prepared for something she had never thought she’d want.

A public remembrance.

For years, she had resisted.

Too many strangers asking questions.

Too many versions of the truth drifting into places where her sons had no voice.

But after the foundation’s launch and Camille’s continued efforts to elevate indigenous climbing narratives, Leotaa felt something shift.

This wasn’t exploitation.

It was continuation.

So when the invitation came from the Wyoming Outdoor Legacy Project to speak at their keynote panel, Stories in Stone, Memory, Climbing, and the Land, she said yes.

She stood in front of more than 200 people that July under a canvas tent pinned to the prairie.

The air was warm and dry, and the smell of pine carried over from the foothills.

She wore a long denim skirt, a woven shawl, and a simple necklace made from carabiner scraps her sons had once used.

She did not read from notes.

She looked at the crowd, then passed them toward the horizon, and said, “My sons were not lost.

They were held.

” A murmur ran through the crowd, not of confusion, but of understanding.

They climbed with reverence, with love, and when one could no longer walk, the other did not abandon him.

He anchored him in place, tied him down to something real, gave him time, food, hope, and then he went to find help.

Not for himself, for his brother.

She paused.

There are people who say they failed, that they vanished.

But my boys didn’t disappear.

You just didn’t know where to look.

The wind picked up, lifting the edge of her shawl, and she smiled faintly.

“Now you do.

” When she finished, the silence that followed was thick and full of breath.

Then slowly, people stood.

No applause, just standing, a field of witnesses.

Later that day, a teenage girl approached her quietly.

She wore climbing shoes slung over her shoulder and had a small notebook tucked beneath her arm.

I want to climb the route, she said.

Not today, not yet, but someday.

Leota placed her hand gently on the girl’s shoulder.

Then climb it for the right reason.

What reason is that? To remember.

That night in the museum that housed the replica portal ledge, Camille hosted a private viewing for local elders, SAR crew, and community members.

The exhibit was now expanded.

Alongside the ledge hung a series of photos, some faded, some recent.

One showed Wikasa teaching Ado how to tie a Munter hitch.

Another, a blurred still from a video, at hanging from a ledge, his face split with laughter.

A new addition was a wall of quotes taken from journals, interviews, and even dreams.

One read, “We climb not to rise above, but to see clearly.

” Otto running wolf.

Another, “If I fall, let it be where I can still see the sky.

” Wicasa running wolf.

The final quote was Leotaas, printed large across the back wall.

“My sons were not lost, they were held.

” That summer, something shifted in the climbing world.

at gyms and outdoor courses across the country.

The story of the Running Wolf brothers was added to curriculum modules, not as a cautionary tale, but as an origin story, a reminder that adventure without care is conquest and that sacrifice isn’t just what you leave behind, but what you stay for.

One notable event was the Stone and Spirit Summit, a national conference of climbers, indigenous leaders, and land stewards.

Camille presented the foundation’s first full report, highlighting over 50 previously undocumented indigenous ascents across the western US, some dating back to the 1940s.

Each climb carried more than technical merit.

Each one told a story.

After the presentation, a young DNA climber named Reena Beay stood and asked the room, “What makes a first descent?” “If our grandfathers climb these walls with no sponsors, no gear companies, no trip reports, why don’t those climbs count?” The silence was not awkward.

It was listening.

From that day forward, the term ancestral line began appearing in climbing publications, map overlays, and guide books.

a nod to the fact that the land had always known the weight of human hands and feet, that not all summits were documented, but they had been reached.

By the end of the summer, a permanent plaque was approved for the portal ledge al cove set to be installed just beside the base, not on the wall itself.

It wouldn’t be flashy, just a small metal plate with a simple inscription.

In memory of Otto and we case a running wolf who climbed with love and descended with hope, anchored not in stone but in each other.

It would take 3 years before weather conditions would allow for safe installation.

But that didn’t matter.

Time had never been the enemy here.

Time was the witness.

Autumn came again, the third since the brothers were found.

the 15th since they first vanished.

But now the date held new meaning.

What had once been mourned in silence was now marked in ceremony.

Each year on the anniversary of the day Wikasa and Atau were declared missing.

The community gathered not to grieve but to remember.

Not just the brothers, but the choice they had made, the bond they had honored, the legacy they had left.

This time, the gathering took place on the foothill ridge overlooking the valley, close enough to see Mount Hooker’s silhouette cut against the evening sky.

Blankets were laid out on the grass.

Fires were lit in small, respectful circles.

There were no formal speeches, only stories.

Alani Greyhawk spoke first, her voice low and even, her long braids tucked beneath her collar.

I remember at trying to convince us to try that route in the dead of winter.

We thought he was crazy.

Wea just looked at him, didn’t say a word, then tossed him a coil of rope and walked away.

That’s how they were.

Otto dreamed it.

Weasa planned it.

They needed each other.

Laughter rippled through the group.

Someone passed a thermos.

The fire crackled.

Another voice picked up the thread.

We searched every inch of that basin.

I remember thinking he had to be somewhere.

He had to.

But the mountain just wouldn’t speak.

Not then.

It waited.

They all nodded.

A silence followed.

Not heavy, just full.

Then Leotaa, wrapped in her son’s old flannel jacket, began to hum a melody so old no one remembered the words.

The song curved up into the night sky, carried by wind and pine smoke.

Some closed their eyes.

Others joined in, barely audible.

When she finished, no one clapped.

No one spoke.

They just let it linger.

Later that night, a young climber from Idaho approached Leotaa.

His voice was quiet, unsure.

I I climbed part of Echoline last week.

Not all the way, just the first two pitches.

I didn’t do it to prove anything.

I just wanted to know what it felt like to be on the wall where they were.

Leota looked at him.

And what did it feel like? He hesitated, eyes flicking up toward the mountain.

Safe, he said.

She smiled.

That was the gift after all.

Not just a route, but a feeling.

the knowledge that someone had been there before, not to dominate the land, but to know it, and to leave behind something worth returning to.

Across the country, the brother’s story continued to spread.

It was no longer just an article in the Alpine Journal or a podcast episode whispered about in climbing gyms.

It had become required reading in outdoor leadership courses at several universities, a case study in wilderness ethics, a lesson in decision-making, but more importantly in values.

Camila Reyes, now overseeing the Miwony Foundation full-time, developed a course module called Climbing with Memory.

It taught technical navigation, yes, but also narrative responsibility.

How to understand who came before and how to leave behind more than footprints or bolds.

The running wolf climb was its centerpiece.

In one session, a student asked, “Do you think they would have survived if they’d brought the satellite phones?” Camille paused, then answered honestly, “Maybe, but then it wouldn’t have been the same climb.

” The class went silent.

In the years that followed, the foundation’s reach extended beyond Wyoming.

Tribal youth outdoor programs sprang up in Montana, Colorado, Arizona, many with mentorship from climbers who had been touched by the brother’s story.

Scholarships were awarded under their names.

Climbing walls were built on reservations not just as training grounds but as places of connection between past and present body and land.

Meanwhile, Detective Lily Menddees, now promoted and overseeing the regional missing person’s division, found herself mentoring younger officers.

One day, she was asked what case had shaped her most.

She didn’t hesitate.

The brothers because it was solved.

No, she said, because it wasn’t just about finding them.

It was about understanding why they climbed in the first place.

That answer began to shape how new cases were handled, how search teams coordinated with tribal leaders, how wilderness disappearances were investigated with cultural sensitivity, how families were centered in the process instead of sidelined.

The brothers had changed systems without ever setting out to.

In mid-spring, 3 years after the discovery of their bodies, the conditions finally allowed the plaque to be installed at the portal ledge al cove.

A small team of climbers, tribal representatives, and SA veterans made the ascent.

The plaque was modest as promised.

It was affixed to the stone with care, not high up, but at eye level, so that anyone who stood there could read it without needing to step into the sacred space.

They anchored it with stainless steel bolts.

They cleaned the rock gently with water and a soft cloth.

They took a moment of silence.

Then they descended.

By summer, word of the plaque had reached climbers across the country.

And while some made plans to see it in person, most respected what it was.

Not a landmark, but a grave, a memory carved into stone.

Many sent small offerings instead, patches, notes, stones, feathers, which were collected and respectfully buried in a quiet circle of earth at the base of the trail head, marked only by a ring of cannons.

It became known quietly as the second anchor.

Later that year, on what would have been Otto’s 36th birthday, Leota hiked to the trail head with Camille and Alani.

The morning was cool and bright.

Wild flowers had started to bloom across the hills.

They sat for hours watching the trees sway.

At one point, Leotaa reached into her bag and pulled out two small stones, one painted with red spirals, the other with a mountain and a rope.

She placed them side by side on a flat rock.

“I used to pray they’d come home,” she said softly.

“Now I just pray that we keep climbing,” Elani nodded.

“We are.

” Camille touched the stones gently.

“And they’re still with us.

” That evening, as dusk fell and the last light faded behind Hooker’s summit, a low breeze stirred the grasses.

It passed through the valley, over ledges, through the trees.

And for those who still listened closely, it sounded just for a moment like rope brushing rock, or maybe like brothers whispering to each other in the wind.

By the fourth spring after the discovery, the brothers story had settled into something larger than remembrance.

It had become a framework, an invisible structure on which others began to build.

Climbers carried it with them like a compass, not for direction, but for orientation.

In a world that often measured worth in summits reached and records broken, Otto and Weasa running wolf had become symbols of something deeper.

Not triumph, but presence, not glory, but devotion.

On a quiet morning in May, a woman named Cara Blackcloud zipped up her gear bag in the corner of her small cabin outside Fort Waki.

She was 27, Lakota, and Shosonyi, and had grown up hearing about the brothers from her older cousins.

But it wasn’t until she stood beneath the portal ledge memorial the previous summer that she truly understood.

She hadn’t spoken much that day.

She hadn’t needed to.

Something had shifted inside her.

She’d spent the following year training.

Her plan wasn’t to replicate the original climb that belonged to them.

But she wanted to ascend the echol line to the ledge.

Not just to stand where they had stood, but to leave something of her own behind.

Not an offering, not a photo, but a record of continuation.

That they had not been the end of the story.

On the second day of the climb, she bivvied just below the al cove, setting up her ledge beside the rock face.

The stars stretched out like rivers of quiet fire.

She didn’t play music.

She didn’t journal.

She lay back against the cool nylon and listened to the wind.

At one point, it rustled through her gear loops.

A small jingle, a whisper.

She closed her eyes and breathed.

The next morning, she made her final push to the ledge.

When she reached it, she did not climb into it.

Instead, she sat across from it, anchoring herself to the wall with her own gear.

For nearly 30 minutes, she simply sat.

Then, she pulled out a notebook and wrote one sentence.

“Your line held.

I’m adding mine.

” She folded the paper, wrapped it in a waterproof sleeve, and carefully clipped it to a bolt hanger on her side of the face opposite the ledge, but aligned.

Two points, two anchors.

Later, she would say it wasn’t about honoring the dead.

It was about continuing the conversation.

That summer, more letters appeared.

Not left carelessly, not in piles, just a few.

hidden in crevices, taped behind gear caches, scrolled on stone in chalk that would soon fade.

Most weren’t names or tributes.

They were words like, “I see you or still here or thank you.

” A kind of call and response between generations.

At the Man Woni Foundation, Camille began cataloging these echotes with permission.

She created a digital archive titled Climbers Who Remember.

Each entry was voluntary, anonymous, unless stated otherwise.

Over time, the archive grew.

Dozens became hundreds, then thousands.

Among them were entries from a black climber from Georgia who had never before felt welcome on the wall, but had found courage in the brother’s story.

a father who had lost his own son to an avalanche and wrote simply, “Now I understand.

” A first generation immigrant who said the climb reminded her of her parents’ journey, though theirs had been through desserts and silence, not stone.

A non-verbal teen climber who uploaded a photo of her sign language interpreter standing beneath the memorial with her.

The caption read, “Love doesn’t vanish.

Back in Lander, Detective Menddees kept her own copy of the archive.

She’d retired from field work, but still gave lectures.

Her favorite slide was one that showed the original photo of the brothers at the trail head.

The dusty Tacoma behind them, Otto flashing a grin, Wasa half smiling with arms crossed.

She would begin every talk with the same line.

This isn’t a crime story.

It’s a love story, just not the kind you’re used to.

One day, a reporter asked if she’d ever found closure.

She thought about it, then said, “I found understanding.

Closure is too tidy for something like this.

In the fall, a new documentary premiered at the Telleluride Mountain Film Festival.

” Directed by a young Lakota filmmaker named Taye Hart, it blended reenactments, archival footage, and animation to trace the brother’s journey.

Not just the physical climb, but the emotional arc of their bond.

The film was called to hold the line.

The final scene was animated in inkwash style.

Two silhouettes ascending opposite cliffs.

They reached a ridge line, paused, then turned to each other, reaching across the divide.

As they touched, the screen faded to white.

It ended with a quote from the recovered journal.

Otto, still alive.

Hold on.

The theater sat in silence after the credits rolled.

No one moved.

No one clapped.

It wasn’t that kind of moment.

In the months that followed, the film toured outdoor festivals, tribal colleges, even some urban high schools far from any cliffs.

Each screening became less about the climb and more about the questions it left behind.

How do we carry each other? What do we leave behind when we fall? What is worth anchoring ourselves to? In early winter, Leotaa received a letter postmarked from Colorado.

Inside was a photograph of two teenage boys, clearly brothers, posing beside the memorial plaque.

No names, no address, just a handwritten note on the back.

They didn’t vanish.

They became part of the mountain.

Leota placed the photo on her window sill beside a smooth rock from the trail head.

A feather Otto had once kept in his truck and the compass Wicassa had carried.

She didn’t cry.

She just sat with them the way she used to sit between their beds, reading to them as children.

That night it snowed again, light and clean, the town slept.

But in the wind that curled through the ridges, and in the hush that settled over the trees, there was a familiar presence, like breath in the cold, like footsteps on frozen ground, like two voices in a language older than maps.

still climbing, still here.

The mountain stood the same.

It always had.

The wind still carved across its flanks, dragging snow and long ghost trails over the ridges.

Ice still formed in the cracks each night, only to melt beneath the weak sun by midday.

The cliffs still cast their long, cold shadows down into the valley, where trees stood like sentinels, patient and unchanged.

And yet, to those who knew the story, Mount Hooker no longer looked the same.

The final snowfall of the year came in early May.

Unexpected and soft.

It blanketed the echol line, powdered the ledges, and dusted the memorial plaque at the al cove with a film so fine it seemed painted on.

The world below continued moving.

Traffic in Riverton, phones buzzing in Lander, emails in inboxes.

But on the mountain, time paused for just a moment.

A trail crew led by a pair of young native rangers made its way to the Big Sandy trail head to check spring conditions.

One of them, Cota Little Feather, had been 12 when the brothers vanished.

He remembered the search.

He remembered the silence.

And now, as a ranger, he walked the same trails they had taken, not to chase them, but to keep them.

At the edge of the treeine, just before the land gave way to stone and air, Cota stopped.

There, half buried in melting snow and last autumn’s leaves, he saw something small sticking out of the dirt.

He knelt, brushed it free, a climbing nut, old, oxidized, but intact.

He turned it over in his palm.

The make was European, the kind Wicassa used.

It must have been dropped during the first search, or maybe on the climb itself.

Somehow, over all these years, it had surfaced.

The mountain had given back again.

He didn’t take it with him.

He placed it at top a nearby rock beside a stack of three small stones, an old ka longforgotten, and walked on.

By midsummer, the Mani Wijoni Foundation announced the launch of its most ambitious project, a high alitude cultural camp designed for native youth to learn climbing skills alongside traditional teachings, story, medicine, language.

It would be called the anchor camp in honor of the brothers.

Leota Running Wolf gave her blessing with one request.

Let them climb with their hearts first.

She visited the site once during construction.

It was quiet then, just tents, a fire pit, and a chalk dusted boulder off to the side with handholds that bore the shine of a hundred eager palms.

She stood alone for a while, then added a final touch to the main sign, a carving of two parallel lines side by side, tapering off into a horizon.

No words, just that.

That summer, the first 20 campers arrived.

They learned to tie knots, repel, ascend.

They learned how to listen to the wind.

At night, they sat around fires and told stories, not just about the brothers, but about the ones who came before them.

They didn’t say the lost, they said the remembered.

One evening, a camper named Malachi, 14, Navajo, small for his age, but fierce on the wall, asked a question that stayed with the group.

Did they know they wouldn’t come back? No one answered for a long time.

Then the instructor, a soft-spoken veteran climber named M, said they knew what mattered more than coming back, and somehow that was enough.

Meanwhile, across the outdoor world, the legacy spread in smaller, quieter ways.

A mural on a climbing gym wall in Seattle showed two figures roped together, not on a summit, but midwall, one hand reaching back.

In Patagonia’s spring catalog, an entire feature was dedicated to indigenousled expeditions.

The cover read, “We were always here.

” And on the back cover, almost invisible for Otto.

and Wikasa, the ones who held.

Camille, now years into her stewardship of the foundation, stepped back from daily operations.

She passed the torch to a young leader who had come up through the early programs, a Lakota woman named Sienna, who had once climbed to the al cove and left a single bead on the bolt.

Camille retired quietly, her final gesture being the donation of the recovered portal edge, not to a museum, but to the cultural archive on the Wind River Reservation.

It belongs home, she said.

There it was not displayed behind glass, but suspended in a quiet circular room surrounded by the sounds of wind, water, and memory.

Children came and sat beneath it.

Sometimes they asked questions.

Sometimes they just sat and always they looked up.

Years passed.

The plaque weathered, the gear aged, but the path never closed.

Each season climbers still walk the echol line carefully, deliberately.

Not to chase a record, but to step into a memory.

Many left nothing behind.

Some left letters.

Others left pieces of themselves.

A fear conquered.

A grief named a love remembered.

And every now and then a new climber would make the journey, reach the al cove, sit across from it, as Cara had once done, and whisper something only the mountain could hear.

Because that was the truth of it.

They had not vanished.

They had become part of the climb.

They had become part of the story.

And for as long as hands grasped rope and hearts beat faster on cold granite, they would remain there.

Two brothers, one love, a climb that never ended.

News

El Mencho’s Terror Network EXPLODES In Atlanta Raid | 500+ Pounds of Drugs SEIZED

El Mencho’s Terror Network EXPLODES In Atlanta Raid | 500+ Pounds of Drugs SEIZED In a stunning turn of events,…

Federal Court Just EXPOSED Melania’s $100 Million Crypto Scheme – Lawsuit Moves Forward…

The Melania Trump grift machine, $175 million and counting. Okay, I need you to stay with me here because what…

Trusted School Hid a Nightmare — ICE & FBI Uncover Underground Trafficking Hub

Unmasking the Dark Truth: How Human Trafficking Networks Can Hide in Plain Sight in Schools In the heart of American…

Native Family Vanished in 1963 — 39 Years Later A Construction Crew Dug Up A Rusted Oil Drum…

In the summer of 1963, a native family of five climbed into their Chevy sedan on a warm evening in…

5 Native Kids Vanished in 1963 — 46 Years Later A Chilling Discovery Beneath a Churchyard….

For nearly half a century, five native children were simply gone. No graves, no answers, just silence. In the autumn…

Native Pregnant Woman & Her Adoptive Mother Vanished in 2009 _ 12 Years Later a Hiker Found This…

They vanished in the summer of 2009 without warning, without witnesses, and without leaving behind anything but silence. One moment…

End of content

No more pages to load