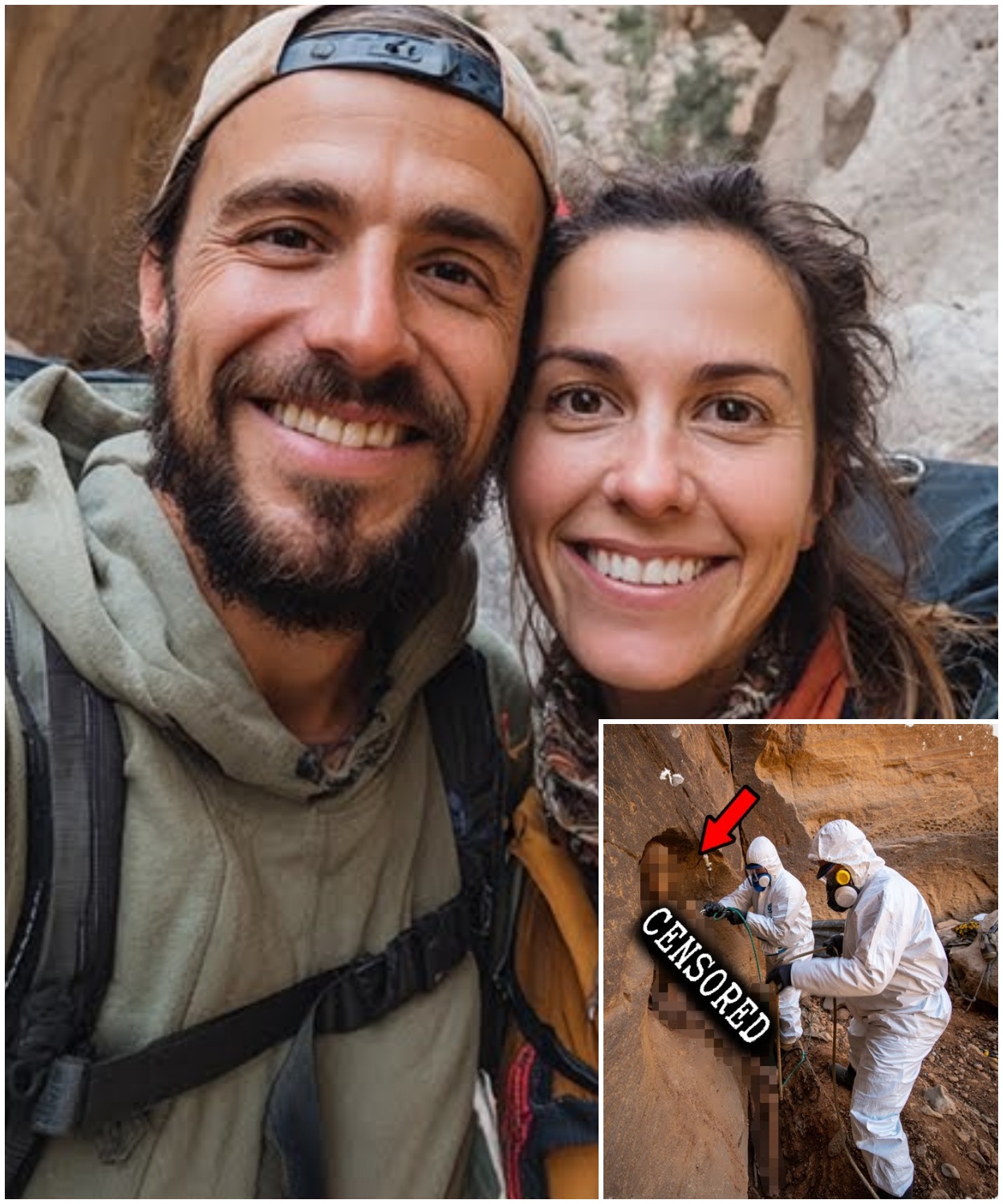

When the cavers descended into a narrow crevice 43 m deep, their flashlights revealed something they least expected to see.

Two bodies frozen in unnatural positions, their ankles bound together.

For 7 months, these people were considered simply missing tourists who had gotten lost in the endless canyons of Utah.

But the truth turned out to be much more terrifying than even the most experienced investigators could have imagined.

This story began eight years ago in early May 2017 when a young couple from Portland set out on a trip that was supposed to be the adventure of a lifetime.

Instead, it became their last.

23-year-old Emily Hartwell worked as a graphic designer at a small creative studio in Portland.

Tall with long brown hair that she usually wore in a messy bun, she was one of those people who radiated calm confidence.

Her social media profile was filled with photos of mountain landscapes and sunsets.

Emily loved nature and tried to get out of the city every weekend.

Her boyfriend, 25-year-old Ryan Macdonald, taught biology at a high school and shared her passion for hiking.

They had been dating for just over a year, and their friends noted how well they suited each other, both calm, thoughtful, preferring quiet evenings by the campfire to noisy parties.

At the end of April 2017, the couple planned a 10-day trip to the littleknown canyons of southern Utah.

They wanted to get away from the popular tourist routes and explore places where few people had ever set foot.

Emily told her best friend Sarah how they studied old geological maps, looking for hidden gorges and pristine natural formations.

It was to be their own personal adventure far from civilization and crowds of tourists.

On May 3rd, they picked up a silver Jeep Compass they had rented at the Salt Lake City airport and headed south.

Emily’s last Instagram post was published on May 5th at 900 p.m.

A photo of their tent against a backdrop of red rocks with the caption, “The stars are closer here than anywhere else on Earth.

” The geol location indicated an area about 80 km north of Paige, Arizona in a remote area known only to experienced rock climbers and cavers.

On May 6th at around 7 a.m., Emily and Ryan left their camp, taking with them backpacks with water, canyoning equipment, and a GPS navigator.

Following tracks that experts would later discover, they headed for a narrow crevice in a sandstone massif, a canyon that did not even have an official name on maps.

Local guides sometimes called it Snake Trail because of its winding descent.

The weather was clear.

The temperature rose to 23°, ideal conditions for hiking.

But that day, a few kilometers from their camp at a small tourist parking lot by a dirt road, there was another traveler.

38-year-old David Coleman had come from Denver in an old dark green Ford Ranger pickup truck.

He was traveling alone, which was unusual for this area, where most people come in groups or pairs.

Coleman worked as a technician for a computer service company, was divorced, and had no children.

outwardly unremarkable, of average height with a receding hairline, a graying beard, and metal- rimmed glasses.

The kind of person you would meet at the grocery store and immediately forget.

However, an incident occurred between Coleman and Emily.

On the evening of May 4th, when the young couple set up camp, Coleman approached their parking spot under the pretext of asking if they had seen a water source nearby.

The conversation started innocently enough, but gradually Coleman began to stare at Emily and make ambiguous comments about how you rarely meet such beautiful girls in the desert.

When Ryan politely pointed him in the direction of the nearest spring and tried to end the conversation, Coleman lingered for another 15 minutes, continuing to ask questions and clearly trying to get Emily’s attention.

The next morning, May 5th, when Emily came out of the tent alone to make coffee on a camping stove, Coleman appeared again.

He said he was passing by and decided to keep her company.

Emily felt uncomfortable and called out loudly for Ryan.

Coleman apologized and left, but the atmosphere was ruined.

Ryan suggested changing campsites, but Emily decided that they would leave for the day to explore the canyon, and by evening, this strange guy would probably be gone.

They were wrong.

When the couple did not return to camp by the evening of May 7th, no one was concerned.

They had no schedule and had not promised to check in regularly.

Emily’s parents only began to worry on May 11th when their daughter did not respond to several messages in a row and did not appear online.

Her mother, Susan Hartwell, called the Portland police, but they advised her to wait.

The young couple was hiking and perhaps simply had no signal.

By May 15th, their concern had turned to panic.

Ryan’s parents joined the search for information.

Through Emily’s social media account, they determined the couple’s approximate location and contacted the Cain County Sheriff’s Office in Utah.

On May 16th, the first search party was organized.

When the rangers reached Emily’s last known location, they found their camp virtually untouched.

The tent was still standing, the sleeping bags were neatly rolled up, and the food supplies were untouched.

But the car was gone.

The silver jeep compass had vanished at a initially investigators assumed that the couple might have decided to move to another location, but their personal belongings, chargers, extra clothes, Emily’s camera were left in the tent.

People don’t leave behind everything they need.

On May 17th, at dawn, a park ranger was patrolling the area within a 5 kmter radius of the camp.

About a kilometer to the west, at the base of a steep cliff, he noticed tire tracks leading to the edge.

As he got closer, he saw something strange.

Fresh skid marks on the red clay soil leading straight to the edge of the cliff, which was about 30 m high.

The ranger called for backup and climbed down a rope.

At the bottom of the cliff, partially hidden by boulders and juniper bushes, lay a silver jeep compass.

The front of the car was crumpled, the windshield smashed, but there was no one inside.

No bodies, no traces of blood, only items scattered around the interior.

Water bottles, maps, rock climbing gloves.

The keys were still in the ignition.

This discovery changed the nature of the search operation.

Now it was no longer just a case of missing tourists.

It was something more sinister.

Forensic investigators arrived at the scene on May 18th.

They found evidence suggesting that the car had not driven off the cliff by accident.

The skid marks were too short, as if someone had deliberately steered the car toward the edge and jumped out at the last moment.

Several dark hairs were found on the driver’s seat, which clearly did not belong to Emily or Ryan.

Both were brunettes, and these hairs had a reddish tint and were shorter.

An experienced investigator from the county police led the investigation.

He had seen a lot in his 23 years on the job, but this case seemed strange to him from the start.

The car had been thrown off a cliff, but there were no bodies.

The camp was intact with everything in place.

Where had the young people gone? The investigator began interviewing everyone who had been in the area in early May.

The database of vehicles entering the national forest showed about 12 vehicles registered at the nearest checkpoints between May 3 and May 7th.

The team of detectives methodically checked each one.

One of the tourists, an elderly couple from California, mentioned a strange man in a green pickup truck who had been parked in the lot for several days.

They noticed him because he seemed nervous and kept walking back and forth as if he were looking for something.

It was early in the morning on May 6th.

By the evening of that day, the pickup truck had disappeared.

Checkpoint records showed that a Green Ford Ranger registered to David Coleman of Denver, Colorado, had entered the property at 2 p.m.

on May 3rd and left at 11:00 a.m.on May 7th.

The investigator immediately requested information about Coleman.

The file was alarming.

David Coleman had a criminal record for harassment obtained 6 years ago in Colorado.

At that time, he had stalked a c-orker, sent her unsolicited messages, and once showed up at her house at night.

The case ended with a suspended sentence and an order to undergo therapy.

In addition, his ex-wife had filed a restraining order 3 years ago, claiming that he had threatened her after their divorce.

The investigator tried to contact Coleman on May 19th.

The phone was disconnected.

No one answered the door at his address in Denver.

Neighbors said they hadn’t seen him in 2 weeks.

Coleman’s employer reported that he had taken 3 weeks vacation and was due to return on May 20th, but did not show up.

On May 21st, an arrest warrant was issued for David Coleman on suspicion of murdering Emily Hartwell and Ryan Macdonald.

His photo appeared in the news and was sent to all law enforcement agencies in the western states.

But Coleman seemed to have vanished.

Meanwhile, the search for Emily and Ryan continued.

Hundreds of volunteers combed the canyons, gorges, and caves within a 50 km radius of their last known location.

They used drones, thermal imaging cameras, and dogs, but they found nothing.

The red rocks of Utah kept their secret.

The victim’s families held press conferences, begging witnesses to come forward.

Emily’s mother, Susan, spoke to the camera with tears in her eyes.

If anyone knows anything, even the smallest detail, please come forward.

We just want our children back home.

Ryan’s father, a retired military man, stood nearby, his fists clenched, his face frozen with grief and anger.

Weeks passed.

May turned into June.

June into July.

The summer heat made the search even more difficult.

Temperatures in the canyons rose to 45° C.

The active search was gradually winding down.

By August, only a few rangers remained in the field, periodically patrolling the area.

And what about Coleman? On May 27th, 6 days after the arrest warrant was issued, the police received an alarming call from the owner of a motel in the small town of Elely, Nevada, 500 km west of the place of disappearance.

A maid had discovered a body in one of the rooms.

The man had hanged himself from the shower pipe using torn sheets.

He had a passport in the name of David Coleman.

Investigators arrived at the scene the next day.

The room was in chaos.

Empty whiskey bottles, an ashtray full of cigarette butts, crumpled newspapers with Coleman’s photo on the front page.

On the bedside table was a note written in shaky handwriting.

I can’t take it anymore.

forgive me, but I didn’t kill them.

I swear I didn’t kill them.

This note divided the investigation into two camps.

Some considered it a lastditch attempt by a guilty man to absolve himself of blame.

Others wondered, “What if he was telling the truth?” Coleman was the prime suspect, but there was no direct evidence linking him to the disappearance of Emily and Ryan.

Yes, he was acting strangely, had a troubled past, and was in the same area on the same days.

But there is a huge gap between suspicion and evidence.

The autopsy confirmed that Coleman died of suffocation, presumably on May 26th.

Toxicology tests showed high levels of alcohol in his blood.

No other substances were found.

In his pickup truck, which was parked in the motel parking lot, forensic experts found camping equipment, a sleeping bag, and several books about the deserts of Utah, but nothing that directly linked him to the missing couple.

However, a digital camera was found in the glove compartment of the car.

The memory card contained photos taken on May 5th and 6th.

Most of the images were landscapes, rocks, and sunsets, but a few frames caught their attention.

They were taken from a distance with a telephoto lens and showed Emily.

She was standing by the tent making breakfast, combing her hair.

The photos were taken secretly from a distance of at least 50 m from behind a bush.

Emily clearly did not know she was being photographed.

This confirmed that Coleman was obsessed with the girl.

But was that enough to call him a murderer? Without bodies, without a murder weapon, without witnesses, the case was at a dead end.

Officially, Emily Hartwell and Ryan Macdonald were listed as missing persons.

David Coleman was only a suspect whose death closed many questions, but provided no answers.

The lead investigator refused to close the case.

He continued to work, reviewing every detail, every piece of evidence over and over again.

But months turned into years.

2017 gave way to 2018.

The families gradually came to terms with the idea that they might never know the truth.

They held symbolic funerals and erected memorial plaques in their hometown of Portland.

Life went on, but the wound did not heal.

In 2019, the lead investigator retired.

Emily and Ryan’s case remained in the archives as unsolved.

New crimes demanded attention and old cases were pushed to the back burner.

It seemed that the mystery of the young couple’s disappearance would remain unsolved forever.

But fate loves unexpected twists.

On December 15th, 2017, 7 months after the disappearance, a group of speliologists from the University of Arizona was conducting research on unexplored carst formations in the same area where the couple had disappeared.

The team was led by Professor Daniel Rivers, an experienced explorer of underground systems.

They were looking for new caves for geological analysis and mapping hidden crevices.

That day, the group of five descended into a narrow canyon located about 4 km northeast of where Emily and Ryan’s car had been found.

It was an area that had not been explored as thoroughly before.

Too narrow, too dangerous for ordinary search parties.

The speliologists moved slowly, documenting every meter.

At a depth of about 43 m, one of the students, 21-year-old Kyle Morrison, noticed a strange smell.

It wasn’t pungent, but it was clearly unnatural for a cave.

He reported it to Professor Rivers, and the group decided to investigate the source.

Following the smell, they went deeper into a side crevice so narrow that they had to walk sideways, sucking in their stomachs.

After about 10 m, the crevice widened slightly, forming a small chamber no more than 2×2 m, and there in the corner, huddled together, lay two bodies.

Kyle Morrison was the first to shine his flashlight on them.

What he saw haunted him in nightmares for years to come.

The bodies were partially mummified.

The dry air of the cave and low humidity had preserved them.

They lay on their sides as if embracing each other.

Their clothes were torn but recognizable.

A man in a gray hiking jacket, a woman in a turquoise t-shirt.

But the most horrifying detail was noticed by Professor Rivers as he approached.

Their ankles were tied, both of them, with a thin nylon rope that had cut into their skin.

Rivers immediately stopped the investigation and called the police on his satellite phone.

The crime scene was preserved.

Over the next two days, a special team of forensic scientists, speliologists, and medical experts carefully removed the bodies from the crevice.

It was an incredibly difficult operation.

The narrow passage, the depth, the need to preserve every piece of evidence.

When the bodies were taken to the Cain County morg, medical examiner Dr.

Elizabeth Chen conducted a thorough examination.

Identification did not take long.

Fingerprints and dental records confirmed that they were Emily Hartwell and Ryan Macdonald.

The families received the terrible news on December 17th.

What they had been searching for for 7 months had finally been found, but it brought no relief, only new pain.

Dr.Chen established the approximate date of death as between May 6 and 8, 2017, which coincided with the time of their disappearance.

The cause of death for both was multiple fractures of the spine, ribs, and skull as well as internal hemorrhaging.

The nature of the injuries indicated a fall from a great height.

But these were not accidental injuries from an unsuccessful descent into the canyon.

It was a vertical fall with tremendous force.

Analysis of the crevice and trajectory showed that the bodies fell from above from the edge of the canyon where the plateau was located.

Directly above the place where they were found, there was an opening in the rock arch, a narrow crevice practically invisible from the surface, hidden by bushes and rocks.

Investigators climbed up and found the place from which, in their opinion, the victims had been thrown.

At the edge of the crevice, they found barely noticeable traces of a struggle.

Scuff marks on the rocks, a shoe print that did not match the victim’s shoes.

Most importantly, there were several drops of blood absorbed into the poorest sandstone.

DNA analysis showed that it was Ryan Macdonald’s blood.

This meant that a struggle had taken place here.

This was where they had been killed.

But the most gruesome detail was discovered during a detailed examination of the rope that had been used to tie their ankles.

The knots had been tied while they were still alive.

The forensic doctor determined this from the nature of the bruises and swelling around the rope.

This meant that the killer first tied their legs, then threw them into the crevice alive or dying.

Why? What was the point? Experienced investigators put forward their theory.

The killer wanted the bodies to remain undiscovered for as long as possible.

>> >> The tied ankles prevented the bodies from scattering during the fall, keeping them compact, which increased the chances that they would get stuck in the narrow crevice and remain hidden.

It was a cold, calculated murder.

The investigation returned to David Coleman with a new focus.

Now it was no longer just a case of a suspicious tourist.

It was a murder case.

Forensic scientists began looking for a connection between Coleman and the place where the bodies were found.

His pickup truck, which was still being held at the police impound lot, was re-examined more thoroughly.

In the back, under the carpet, they found microscopic traces of red clay, the same composition as that found on the plateau above the crevice.

Three short nylon threads identical to the rope used to tie up the victims were found in the folds between the seats.

Forensic analysis confirmed that these were pieces of the same rope.

Upon re-examining the photos from Coleman’s camera, experts noticed a detail they had missed before.

In one of the photos taken on May 5th at 7 p.m., two figures walking along the trail are blurred but clearly visible in the background.

Analysis of the enlarged image showed that they could be Emily and Ryan.

Their clothes matched, but more importantly, the direction they were walking in led to the canyon where their bodies were later found.

So Coleman wasn’t just photographing Emily at the camp.

He was following the couple, possibly the entire day on May 6th.

The investigation team reconstructed the approximate chronology of those last hours.

On the morning of May 6th, Emily and Ryan left the camp and headed for a little explored canyon.

Coleman, obsessed with the girl and angry at her rejection, followed them at a distance.

He was an experienced hiker and knew how to move quietly.

Perhaps he didn’t plan to kill them.

Perhaps he just wanted to scare Ryan, intimidate him, and force Emily to stay with him.

But something went wrong.

Somewhere on the plateau, at the edge of a crevice, a confrontation took place.

Maybe Emily and Ryan noticed they were being followed.

Maybe Coleman himself made contact.

A fight ensued.

Ryan, trying to protect Emily, was struck, perhaps with a rock, perhaps with a fist.

The blood at the edge of the crevice was his.

Coleman may not have intended to kill them, but the situation got out of control.

or more likely, given their bound legs, it was premeditated murder.

Coleman prepared.

He brought a rope.

Perhaps he threatened them with a weapon, forced them to tie each other’s legs together.

Then he pushed them into the crevice, believing they would never be found in this deep, hidden hole in the ground.

After the murder, Coleman returned to their camp.

He took the keys to their car.

Perhaps he planned to simply steal it and drive far away.

But then he changed his mind.

It was too risky to drive a car belonging to missing people.

Instead, he threw the jeep off a cliff, making it look like an accident.

Then he left the area on the morning of May 7th, but his conscience tormented him or fear.

When photos of the victims appeared in the news, when he realized that the police were looking for him, he couldn’t take it anymore.

The note in the motel, I didn’t kill them.

Was it the truth or a desperate lie from a man who couldn’t live with what he had done? Experienced specialists believed that Coleman was lying in the note.

All the evidence pointed to him.

But another part of the investigation wondered, “What if it was true? What if there was someone else?” An interesting clue was found in the archives.

On May 18th, a week after the car was found, one of the rangers reported seeing a strange man nearby.

The man was running through the bushes when he noticed the ranger and hid behind some rocks.

At the time, no one paid much attention to it.

The area was frequented by poachers, marijuana enthusiasts, and just plain strange people who avoided society.

But now, this episode took on new meaning.

However, there was no additional evidence.

The case was officially closed on December 28th, 2017 with David Coleman found guilty of the murders of Emily Hartwell and Ryan Macdonald postumously.

The families were given the right to hold funerals.

A service was held in Portland on December 29th.

Hundreds of people came to say goodbye to the young couple whose lives had been so brutally cut short.

Emily’s mother, Susan, spoke at the ceremony.

Her voice trembled, but her words were powerful.

My daughter loved life.

She loved the mountains.

She loved nature.

She loved Ryan.

They didn’t deserve this ending.

But I want to believe that where they are now, they are together under the same stars they loved to watch.

Ryan’s father said in a firm voice, “My son was a good man.

He protected those he loved.

I know he fought to the end and I am proud of him for that.

After the funeral, the family established a foundation in memory of Emily and Ryan aimed at educating tourists about safety rules in the wilderness and supporting victims of harassment and stalking.

Because, as it turned out later, Coleman’s story could have ended differently if the system had taken his past offenses more seriously.

In 2018, a journalistic investigation revealed that Coleman’s suspended sentence for harassment six years earlier had been too lenient.

He did not undergo therapy and was not supervised.

A restraining order issued by his ex-wife was not added to the federal database due to a bureaucratic error.

The system failed and two young lives paid the price.

The case of Emily and Ryan became a catalyst for legislative changes in several states.

Penalties for stalking and harassment were toughened and mandatory psychological evaluations were introduced for those given suspended sentences for such offenses.

But for their families, this was little consolation.

The investigator who led the case considered it closed, albeit incomplete, until his death in 2021.

We found them.

We know who did it.

We know how.

But we will never know exactly why.

Why one person decided they had the right to take the lives of two others.

And that’s the scariest part of the job.

Realizing that there isn’t always a logical explanation for evil.

However, some questions remained unanswered.

Why did Coleman tie their legs before throwing them off the bridge? Was it an attempt to slow them down, to give himself more time to escape, or was it some kind of twisted symbolic revenge? Psychologists who studied the case suggested that the tying up could have been a way of controlling them.

Coleman, having lost control of the situation with Emily rejecting him, was trying to regain that feeling of power by physically restraining his victims.

There was also the question of the exact time of death.

Dr.Chen could not say for sure whether Emily and Ryan died instantly upon impact or spent some time at the bottom of the crevice, dying from their injuries.

Judging by the position of the bodies, embracing each other, it is possible that they were conscious for at least a few minutes.

This thought haunted their relatives the most.

This place became a reminder that even in the most beautiful corners of the world, danger can lurk, that not all people are good, and that you need to trust your instincts when something seems wrong.

Emily felt that Coleman was strange.

Ryan suggested leaving, but they stayed, thinking it was paranoia, that everything would be fine.

That decision cost them their lives.

The story of Emily Hartwell and Ryan Macdonald is not just a crime report.

It is a lesson that evil often comes in an ordinary, unremarkable guys.

Coleman did not look like a monster.

He was an ordinary middle-aged man with an unhappy marriage and a boring job.

But inside him lurked chaos, an inability to take no for an answer, a dangerous obsession.

This story is also about the importance of early intervention.

If Coleman had been required to undergo proper therapy after the first incident of harassment, if he had been properly monitored, perhaps the tragedy could have been avoided.

But the system failed, and the consequences were fatal.

Today, 8 years after the tragedy, the case is officially closed.

The bodies are buried, the perpetrator is dead, and questions remain.

Utah’s canyons continue to attract thousands of tourists each year seeking adventure and the beauty of the wilderness.

But those who know this story look at these majestic red rocks with a different feeling.

Not only admiration but also unease.

News

Ilhan Omar ‘PLANS TO FLEE’…. as FBI Questions $30 MILLION NET WORTH

So, while Bavino is cracking down in Minnesota, House Republicans turning the heat up on Ilhan Omar. They want to…

FBI & ICE Raid Walz & Mayor’s Properties In Minnesota LINKED To Somali Fentanyl Network

IC and the FBI move on Minnesota, touching the offices of Governor Tim Walls and the state’s biggest mayors as…

FBI RAIDS Massive LA Taxi Empire – You Won’t Believe What They Found Inside!

On a Tuesday morning, the dispatch radios in hundreds of Los Angeles taxi cabs suddenly stopped playing route assignments. Instead,…

Brandon Frugal Finally Revealed What Forced Production to Halt in Season 7 of Skinwalker Ranch….

The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch became History Channel’s biggest hit. Six successful seasons documenting the unknown with real science and…

1 MINUTE AGO: What FBI Found In Hulk Hogan’s Mansion Will Leave You Shocked….

The FBI didn’t plan to walk into a media firestorm, but the moment agents stepped into Hulk Hogan’s Clearwater mansion,…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage…

1 MINUTE AGO: Police Were Called After What They Found in Jay Leno’s Garage… It started like any other evening…

End of content

No more pages to load